Advocating for the warehouse

Haro on the warehouses?! On the benches of the National Assembly, where the first reading of the Climate and Resilience Bill has just been completed, with some 7200 amendments, a defendant has been summoned: the warehouse. This archetype of peri-urban France was invited into the debates during the examination of the provisions on soil artificialisation, which it is accused of feeding. The figures are indeed impressive: even though they represent less than 1% of built-up areas, the total surface area of warehouses has doubled in the last five years, while in twenty years their proportion of total economic buildings has tripled. And the growth of commercial real estate is not about to stop. At the time of the corona, online commerce is exploding – more than 20% by 2020 worldwide – and it is a safe bet that the shopping habits developed by many of us during the pandemic will not disappear with it. France’s territories are not done with warehouses.

In the lawsuit against them, the damage to biodiversity is not the only accusation: there is a trial in aesthetics – the famous “ugly France” featured on the front page of Télérama in 2010 – as well as a serious accusation, at a time when the State is investing in the hearts of small and medium-sized cities: the unfair competition made by e-commerce to small businesses. The warehouse is designated as the new public enemy number one of downtown commerce, which is already quite weakened, and which is likely to be even more so by the pandemic, including in the centers of large cities. The controversies surrounding Amazon are not for nothing in the criticisms aimed at warehouses, caught in the negative halo effect around the company created by Jeff Bezos.

There is something surprising in this debate. Because, in the chaos of our lives and economies, which have been disrupted by the pandemic, the few remaining elements of continuity are largely due to the efficiency of one sector: logistics, of which the warehouse, like the truck or the parcel, are the totemic objects. What made the first confinement possible and bearable in the era of mass consumption, if not the robustness of logistics chains? What do all successful vaccine strategies have in common if not a prioritized focus on logistics? One must read the Peterson Institute for International Economics’ fascinating account of the Trump administration’s May 15, 2020 Operation Warp Speed on vaccines to understand what a supply chain is and how strategic it is.

The pandemic, since its beginning, reminds us of Eisenhower’s famous words: “planning is everything, the plan is nothing”. And logistics is nothing other than a permanent art of planning. In France, this other type of mobility, that of goods rather than people, has long been the blind spot of mobility policies. Seen as ancillary, considered as a high-risk social sector, it is often viewed solely in terms of its negative impacts, not without a certain arrogance on the part of administrative elites. Hence a mixture of laissez-faire, whose policy on the establishment of warehouses is subject to a boomerang effect, and regulation in fits and starts, when there is social unrest and threats of blockades by truckers.

Whether it has the face of Ever Given blocking the Suez Canal for six days, a batch of Pfizer doses, a diesel delivery truck blocking the street or a warehouse on the periphery of a city, the logistics issue is nonetheless on the political agenda. It will stay there, if only for environmental reasons. This is an excellent thing. First, because the mobility of goods and people are linked: the reduction of travel between home and work, and the increase in teleworking practices will lead to new flows of goods and services. Secondly, the logistics issue puts the spotlight on the France of the peripheries and the suburbs, a France that is appreciated and sought after by our fellow citizens, as shown by the Kantar survey on medium-sized cities published last November by La Fabrique de la Cité.

This France is not a non-place, a “nowhere” to use David Goodhard’s analytical grid. According to the author of The Road to Somewhere, who in 2017 theorized the distinction between “the people of anywhere” and “the people of somewhere”, a world separates the former, endowed with cultural, social and financial capital, at ease everywhere, mobile and attentive to innovation, from the latter, anchored in a place, strong only in their family capital, sometimes under house arrest, who experience globalization as an attack on their way of life and the future of their children. The logistics system, whose maps are being reshuffled by Amazon and the expansion of its footprint in the territories, is transforming these “somewhere” people into “anywhere” people: the warehouse is the place of service that puts the executive living in central Paris on an equal footing with the employee living an hour and a half’s drive from the big city. It is becoming an essential link in the local economy, whether real or perceived, which is being created thanks to digital technology.

To prevent the ecological transition from playing the same role as globalization, it is time to look at the suburbs, the kingdom of logistics, and its symbols – the traffic circle, the warehouse – as a territory in its own right, appreciated by those who live there. Rather than trying to uninvent it, let’s shape it, adapt it to the era of ecological transition by working with them rather than against or without them. And let’s reexamine our preconceived ideas. The results of a fascinating study on the climate performance of online commerce, recently published by the German daily Handelsblatt, invite us to do so. According to consultants from Oliver Wyman and specialists from Logistics Advisory Experts GmbH, a subsidiary of the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland, the climate balance of online trade is better than that of fixed trade. According to their calculations, the CO2 emissions calculated in stationary trade are on average 2.3 times higher per product sold than in e-commerce. The subject of CO2 is certainly not soluble in biodiversity, but this example suggests at least that working on sustainable logistics, on its practices and its territories, does not lend itself to shortcuts. “France has become a distant landscape” writes Aurélien Bellanger in his novel L’aménagement du territoire. It is time to reacquaint ourselves with it, warehouses included. – Cécile Maisonneuve, president

→ This editorial is excerpted from Cécile Maisonneuve’s bi-monthly columns and can be found in its entirety on the L’Express website (in French).

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Lisbon beyond the Tagus

Helsinki : Planning innovation and urban resilience

A warm tomorrow

Behind the words: food security

Nature in the city

“Once Upon a Time”…

Breathless Metropolises

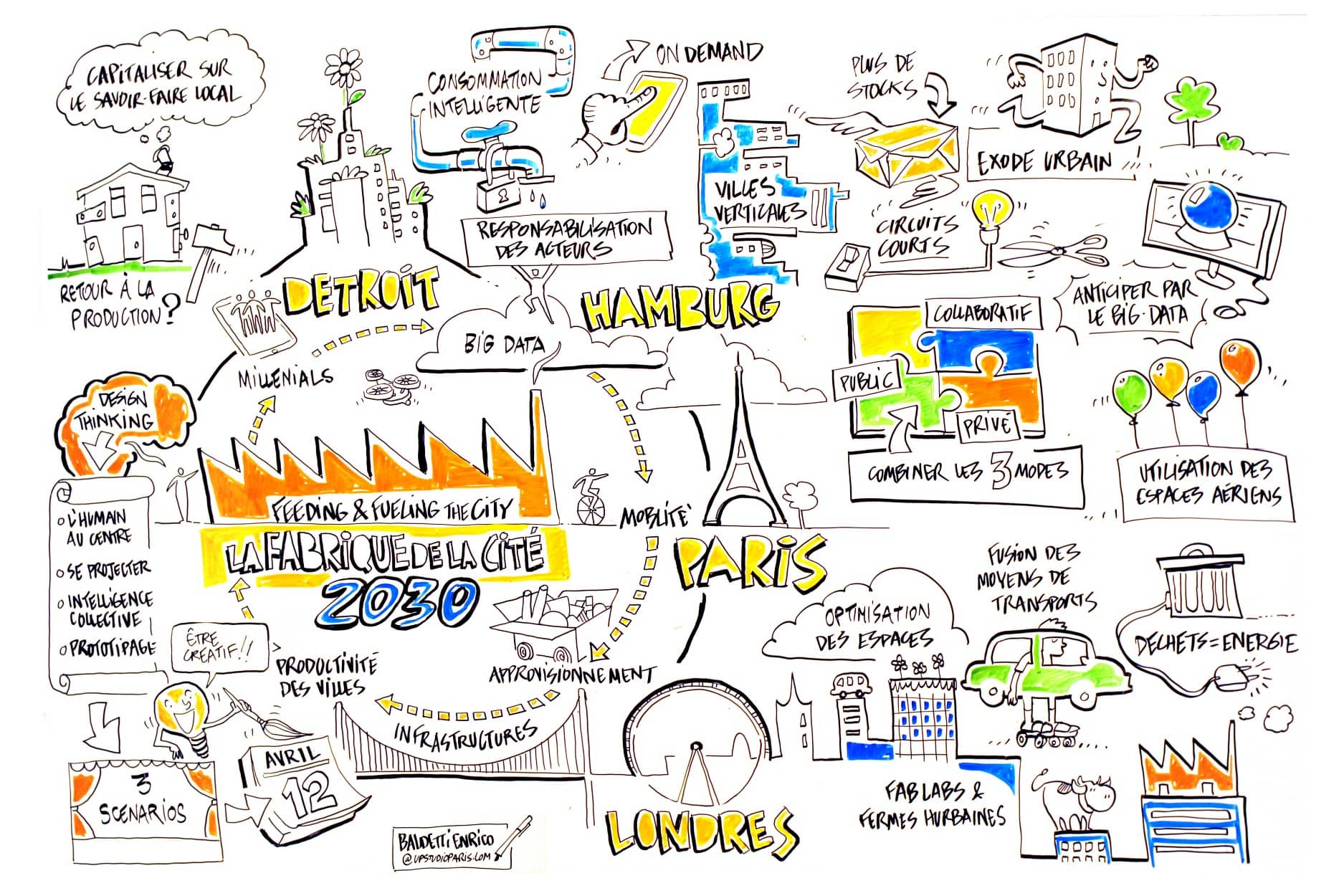

Feeding and fueling the city

Towards the Amazon city?

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.