Behind the words: density

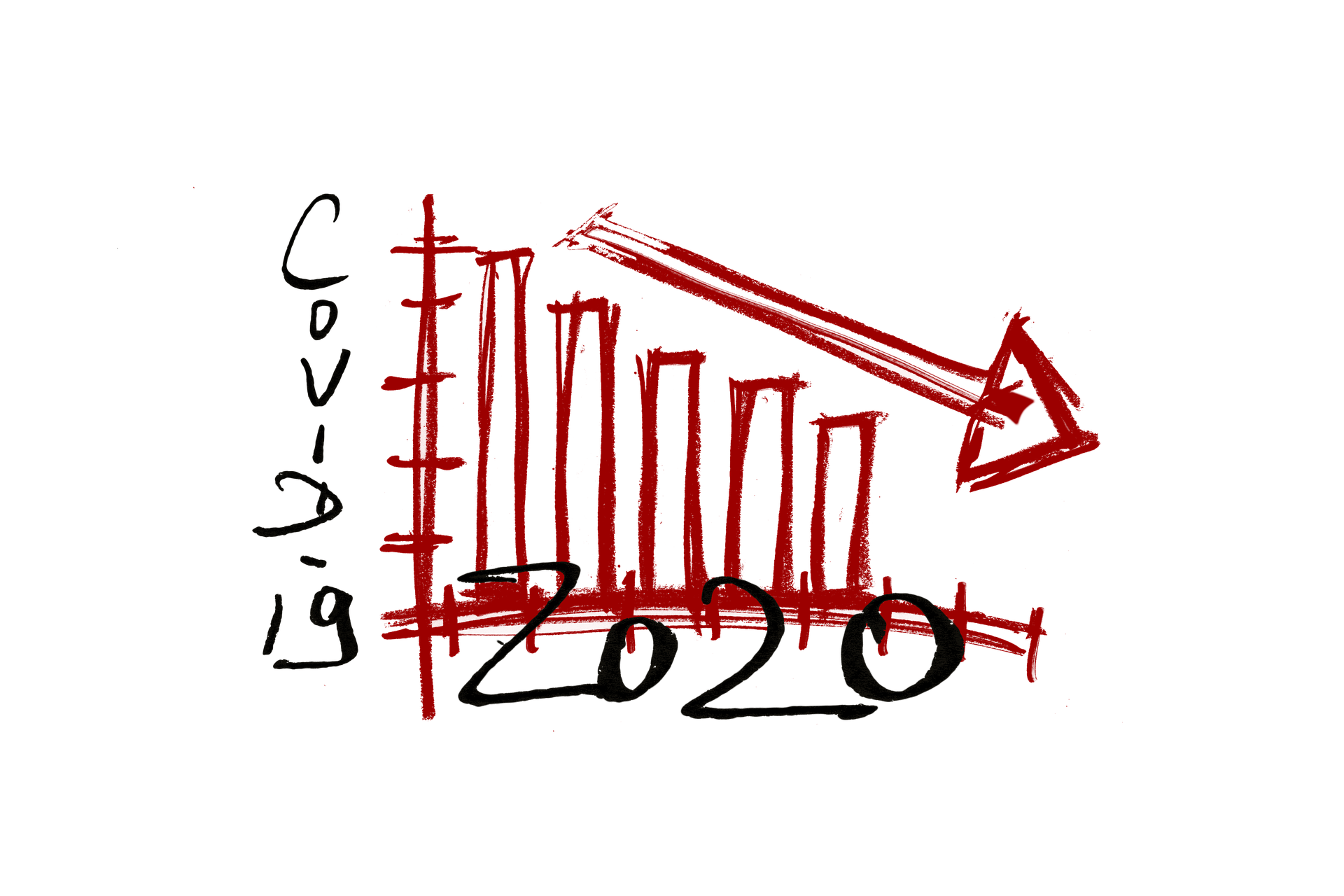

Is urban density responsible for the spread of coronavirus in urban areas?

“An enemy in the fight against the coronavirus [i]“, “a godsend for the coronavirus [ii]“: since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, much commentary has been published on density, commonly regarded as the primary explanation for the fast development of the epidemic in densely populated cities like New York City. The New York Timesexplains that when New York had 13,000 confirmed cases of coronavirus, Los Angeles, a city known for its spectacular sprawl and much less densely populated, had only 500 [iii]. Steven Goodman, an epidemiologist at Stanford University, notes that “density is really an enemy in a situation like this [iv]”. In France, Jean-François Delfraissy, chairman of the Covid-19 scientific council, recently declared, with regard to the coronavirus-related disease, that it is a “disease of big cities, of urban areas [v]”.

These analyses rightly identify a link between the epidemic and density, but err in making density the main factor in the spread of the epidemic. Indeed, the dynamics of the epidemic are linked not to population density per sebut to the density of social contacts. This explains why certain densely populated cities have been relatively unaffected by Covid-19: this is notably the case of Singapore, a city-state with a highly constrained territory but where the number of deaths linked to the epidemic remains very low. Conversely, less densely populated areas are by no means immune to epidemics; indeed, it seems that the first cases of coronavirus detected in Europe and the United States all originated in the urban periphery. In this regard, Michele Acuto, Professor of International Urban Policy at the School of Design of the University of Melbourne, notes that the pandemic tells “a story of connections between peri-urban spaces and between rural and urban, in places that often do not appear on the world map [vi]“, citing the example of the contamination of a small town in Bavaria, attributed to its relationship with the outskirts of Wuhan. Chloë Voisin-Bormuth, director of studies and research at La Fabrique de la Cité, confirms this diagnosis: “the hubs usually cited, namely metropolitan areas, disappear to reveal a geography of industrial establishments, places of residence and private relations. This geography is that of the periphery, which thus reveals itself distinctly as a place of habitat, mobility, and interpersonal relations, where people rub shoulders and, therefore, contaminate each other“.

This last point is essential: what the epidemic reveals is the existence of clusters favored not by density per sebut by physical proximity between individuals. These clusters are therefore likely to form anywhere, regardless of population density. “The discriminating factor is less density than modes of social interaction. It is for this reason that clusters can be found in any type of city, from the largest and densest (Wuhan, New York City) to the smallest (villages in northern Italy) and that cities like Hong Kong and Singapore have managed to contain the epidemic despite their very high density [vii],” notes Chloë Voisin-Bormuth.

As the dynamics of the epidemic are linked to the density of social contacts, it is by limiting social contacts that we can hope to curb the epidemic. And if living in a less dense area, where physical distancing is mechanically easier to implement, makes it easier to avoid social contacts, solutions also exist in dense metropolises. They include adopting a strategy based on widespread testing, the isolation of suspect cases, and protective gestures (physical distancing and masks) by the greatest number. Avoiding large gatherings and using private cars, which are less risky than public transport, can also allow individuals to avoid the social contacts that encourage the spread of the epidemic. In the post-lockdown period, this observation should lead some public transports users to shift to the car in the city centers of major metropolises. Gegative consequences can be anticipated: congestion, reduced air quality, etc.

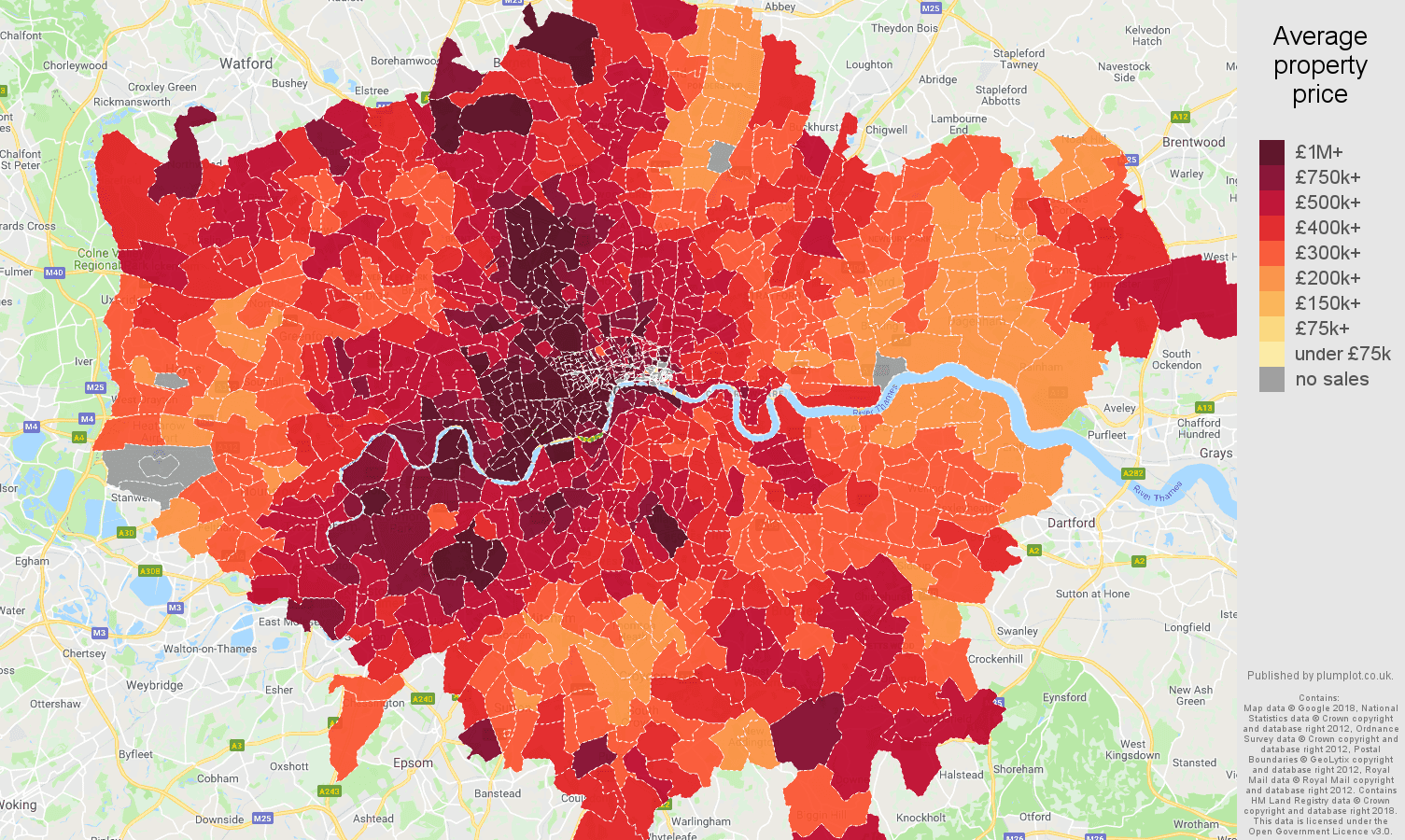

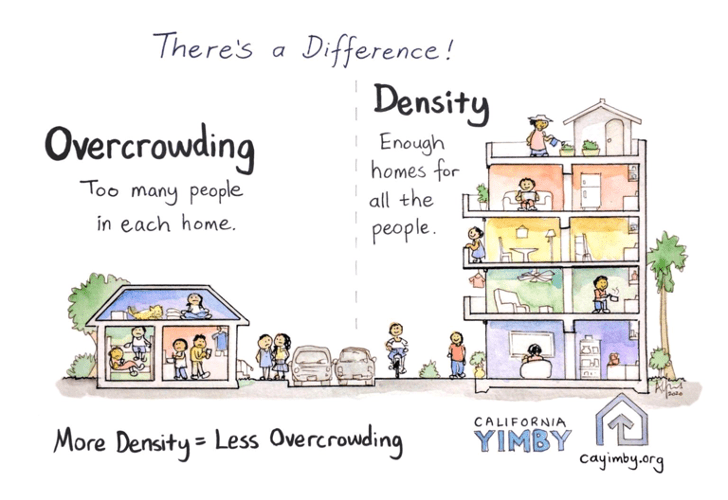

While urban density is undeniably a health risk factor in times of epidemics, it is not the ideal culprit that some people would like to make it. Indeed, it is not density in the strict sense that has penalized the metropolises affected by the coronavirus epidemic, but rather the density of social contacts, to which must be added the differentiated management, from one city to another, of the epidemic and its impacts. The example of the heavy toll paid by the department of Seine-Saint-Denis in France confirms this observation: the department, which has the youngest population in France, experienced a very high excess mortality at the height of the epidemic. With 6,800 inhabitants/m2, it is nevertheless three to four times less dense than the city of Paris. While the factors explaining this excess mortality are numerous and complex (poverty, the nature of the jobs occupied by the inhabitants of Seine-Saint-Denis, etc.), one should not be overlooked, the direct consequence of which is a high density of social contacts: the over-occupation of housing. “Seine-Saint-Denis is particularly affected by over-occupation conditions with more people in smaller housing units (approximately 26.5m² per inhabitant compared to 30.5m² per inhabitant in Hauts-de-Seine and 30.1m² in Val-de-Marne) [viii]“,as stated in the Departmental Action Plan for Housing for the Disadvantaged of Seine-Saint-Denis published by the DRIHLin 2014. Robin Rivaton writes that “the geography of the pandemic shows (…) the high toll paid by working-class neighborhoods, where housing conditions are the most degraded. In New York City, 16 of the 25 neighborhoods with the highest infection rates have the highest levels of overcrowding [ix]”. Here, therefore, it is over-occupation, a factor of social interaction, and not population density in the literal sense that seems to have favored the spread of the epidemic.

A complex concept at the heart of numerous misunderstandings

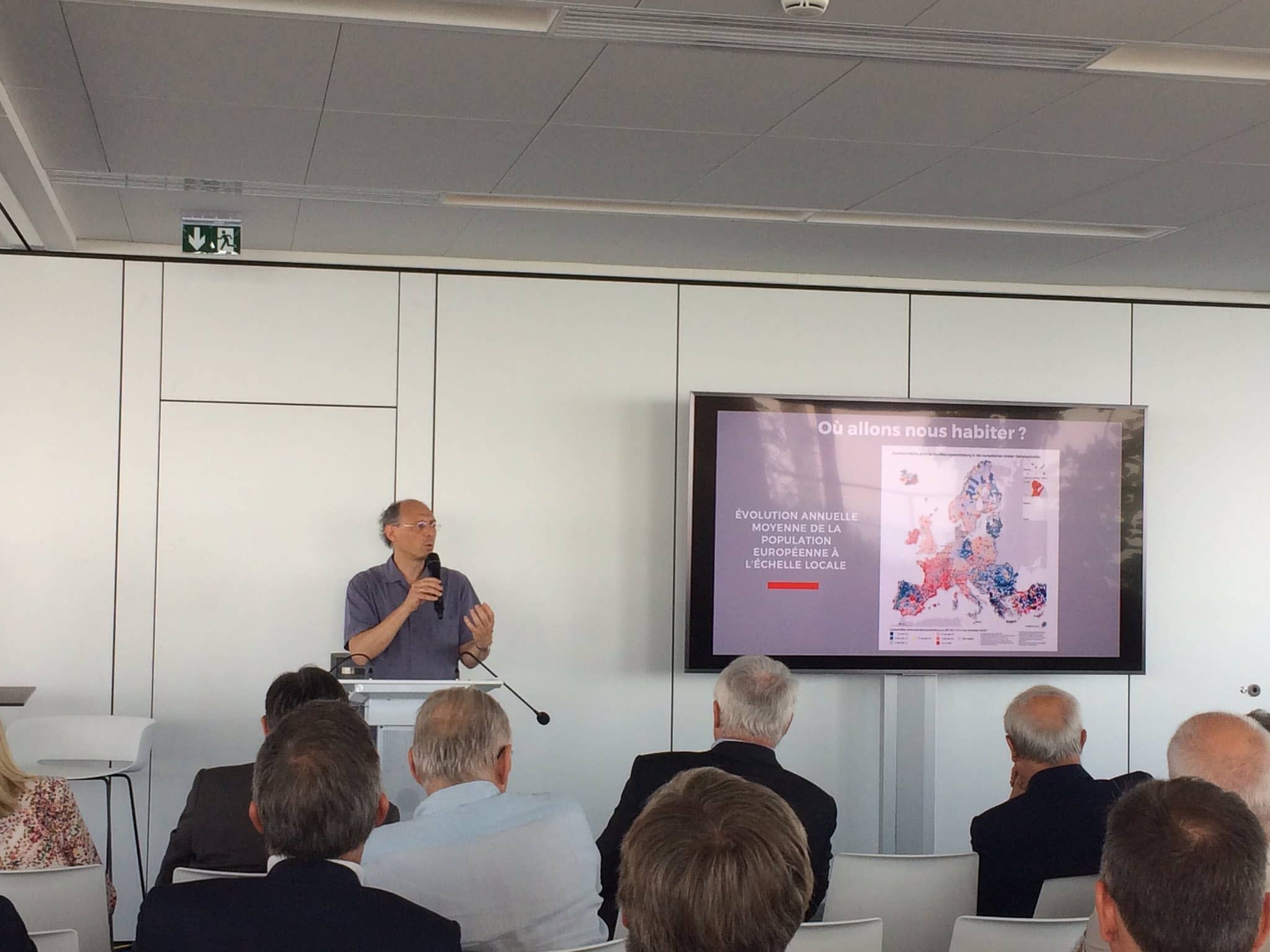

Why was density so quickly seen as the cause of the rapid spread of the epidemic in urban areas? Probably because it is a complex concept, the nuances of which are sometimes unknown. Literally, density refers to “the ratio between a statistical indicator, a number of ‘individuals’ (in the statistical sense: number of inhabitants, doctors, housing, production units, etc.) or other parameters (such as the linear course of a motorway network, for example) and a surface area [x]“. However, a distinction must be made between internal or “residential” density, which refers to the ratio between the number of dwellings and the surface area, excluding public roads, and external density, which refers to the number of inhabitants per square kilometer. This distinction makes it possible to conclude, counter-intuitively at first glance, that “a neighbourhood of overcrowded high-rise buildings often has a lower external density than a suburban area [xi]“. Éric Charmes makes the same observation, underlining at the same time the complexity of defining density:

“Urban planners and developers favor a morphological approach to density. To understand the built density, it is often recommended to use the coefficient of land area (i.e. the ratio between the surface area of the block and the surface area actually occupied on the ground by the buildings) multiplied by the number of levels. However, this measure remains imprecise. In particular, results vary greatly depending on whether or not the area taken into account for the calculation of the right-of-way coefficient includes green spaces or traffic lanes. The densities calculated in this way are also very poor indicators of built-up form. With a built density equal to 1, one can have a one-story building covering the entire plot or a four-story building covering a quarter of the plot. Thus, because of the large spaces left free, many large developments have a density equivalent or even lower than that achieved by individual strip housing [xii]“.

Understanding this complex notion is made even more difficult by the multiplicity of perceptions and experiences attached to it. In the 19thcentury, density was considered synonymous with promiscuity and therefore a source of preoccupation. It was then linked to the arrival of rural populations who came to work in factories. Baron Haussmann also showed a strong aversion to density (understood as the ratio between public space and built space) and over-occupation of housing. He was responsible for the implementation of a hygienic urban planning policy, which led to the invention of a city that was both dense and healthy thanks to the central place devoted to public space and an architecture of blocks that allowed for the design of apartments that facilitated air circulation. However, the appearance of this form that combines density and health failed to transform perceptions, which continue to associate the notion of density with the accumulation of inhabitants and thus with foul air that could precipitate the spread of disease. In addition to these perceptions, which stem from the confusion surrounding the definition of density and contribute to its perpetuation, there are also very different perceptions of density. Thus, the socio-economic profile of the inhabitants of a neighborhood, street or municipality has a significant influence on the perception of its density; there are “high densities that are well lived and badly lived“. Similarly, the presence of infrastructure, the quality of architectural form, the availability of essential services of daily life “can play a compensatory role in relation to the assessment of medium or high densities [xiii]“. The Institut Paris Régionconfirms this diagnosis: “many operations have thus shown that the acceptance of density is linked to architectural and urban forms, to their location in relation to the road network, to the treatment of public space, to the presence of vegetation or to the level of services and facilities [xiv]“. At the same density, experiences will vary greatly depending on the shape of the building: architecture close to the ground, tall buildings, individual housing… Thus, “’close to the ground’ architecture is better accepted because it induces intimacy and a feeling of well-being. Conversely, height is considered ‘oppressive’. The architectural forms given to density therefore play a major role in its acceptance by the population [xv] ,” notes a study by the Departmental Directorate of Territories. “The notion of high density conveys fears, or on the contrary attracts urban planning actors such as the population. (…) Density is therefore largely subjective and felt [xvi]“. Geographers Patrick Poncet and Olivier Vilaça confirm that “the density of the population or the size of an urban area gives a partial view of the city and urbanity; it is also necessary to take into account what we call spatiality, i.e. the ways of living in the city, of travelling around it [xvii]“. Two urban fabrics of strictly equal density can therefore be characterized by widely diverging degrees of acceptability, a fact that calls for a relativization of the overly clear-cut analyses of the advantages and disadvantages of high urban density.

The importance of representations and feelings in the acceptability of density explains the heated debates surrounding the notions of urban density and urban sprawl. In France, a public policy to encourage home ownership was implemented as early as the 1970s, encouraging the emergence of a national preference for individual housing and home ownership. This policy lasted for several decades: thus, the “France of homeowners” was, with thirty-three years difference, the leitmotiv shared by presidential candidates Valéry Giscard d’Estaing and Nicolas Sarkozy. It has proved efficient: France had 35% of homeowners in 1954 (INSEE) and 65% in 2015 (Eurostat). This public policy, combined with the low cost of land and the increased efficiency of car mobility, allowing higher speeds for the same travel time, led to urban sprawl, i.e. “development that reduces residential density” (Jean-Marc Offner). Urban sprawl is associated with an imaginary low density and a specific architectural form: the single-family home. The generalization of the automobile thus opens up a different path from that of the compact city, “a slow pre-war city where density was necessary for the implementation of individuals’ activity program”, Jean Coldefy points out.

From the 1970s onwards, however, many voices called for a halt to urban sprawl. France adopted legislative and regulatory instruments designed to combat soil artificialization and the exploitation of a rare resource: space. Density is increasingly praised as being more economical in terms of space and associated with less car use and therefore less air pollution. “In fact, numerous studies have confirmed the existence of a strong interaction between urban density and energy consumption linked to transport. They have shown that high densities are associated with shorter travel distances and a modal split to the disadvantage of the car, resulting in lower energy consumption for travel,[xviii]” notes Hélène Nessi. This observation leads some observers to equate dense or compact cities with energy sobriety. However, while these arguments are well-founded, the dense city is not a uniform solution to the challenge of the ecological transition of cities, and the effect of densification on the rate of soil artificialization must be qualified. Jean-Marc Offner thus points out that “an entirely peri-urban France would increase the proportion of artificial land from 9% to 10%, 11% at most, a much lower percentage than in the Netherlands“. At the same time, density is by no means a panacea in terms of environmental protection and the fight against climate change. Hélène Nessi thus hypothesizes that “compensatory” mobility, characteristic of dense cities, would neutralize the benefits of lower automobile use in these cities:

“The consideration of weekend mobility and long-distance travel significantly changes the results of studies on the advantages of the compact city. In 1990, Swedish research by Vilhelmson emphasized the importance of long-distance mobility and suggested that density would create new travel ‘opportunities’: the time and money saved from short-distance trips that could be used for long-distance trips. Kennedy, in 1995, adds to this hypothesis the link between leisure and long-distance mobility. The reduction in daily trips is compensated for by their increase to more distant places of leisure, particularly by air. This mechanism could cause density to lose the virtues it is supposed to have, since the inhabitants of dense cities would be more likely to want to escape on weekends”.

Cécile Féré also points out that “the search for density, which is supposed to lead to energy savings, in fact produces counter-intuitive effects: the over-consumption of energy in buildings, for example, or the greater leisure mobility of its inhabitants in search of green spaces, whereas the leisure mobility of peri-urban dwellers is less due to the ‘barbecue effect’ (Orfeuil, Soleyret 2002). The environmental benefits of density would thus be found rather in intermediate densities [xix]“. The trial of urban density thus ignores the complexities and nuances inherent to this poorly understood notion. Behind this debate about the respective vices and virtues of dense cities and less densely populated areas, lies is in fact another, political debate about lifestyle choices.

[i] Courrier international, Crise sanitaire. À New York, la densité de population ennemie de la lutte contre le coronavirus, 24 mars 2020.

[ii] Jean-François Bouvet, Circulation et virus : la terrible équation parisienne, Le Point, 16 mars 2020. URL : https://www.lepoint.fr/sante/circulation-et-virus-la-terrible-equation-parisienne-16-03-2020-2367367_40.php

[iii] Brian M. Rosenthal, Density Is New York City’s Big ‘Enemy’ in the Coronavirus Fight, New York Times, 23 mars 2020. URL : https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/nyregion/coronavirus-nyc-crowds-density.html

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Cité dans : Elsa Dicharry, Comment le coronavirus va changer le visage des grandes villes, Les Échos, 27 avril 2020, URL : https://www.lesechos.fr/idees-debats/sciences-prospective/comment-le-coronavirus-va-changer-le-visage-des-grandes-villes-1198481

[vi] https://www.citylab.com/design/2020/03/coronavirus-urban-planning-global-cities-infectious-disease/607603/

[vii] https://www.lafabriquedelacite.com/publications/une-rue-nommee-desir/

[viii] http://www.drihl.ile-de-france.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/pdalpd_-_93_-_2014_2017_-_version_finalisee_cle08bbf1.pdf

[ix] Robin Rivaton, Se serrer, sans s’entasser, L’Express, 23 avril 2020, page 57.

[x] Glossaire : Densité. Géoconfluences, ressources de géographie pour les enseignants. Dernière modification : octobre 2017. URL : http://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/glossaire/densite

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] https://www.aurm.org/uploads/media/f7018dfe821c61135f2016a5d277c984.pdf

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Damien Delaville, Laurence Nolorgues. Les espaces urbains au défi de la densification. Note rapide de l’Institut Paris Région n°836, février 2020. URL : https://www.institutparisregion.fr/fileadmin/NewEtudes/000pack2/Etude_2313/NR_836_web.pdf

[xv] http://www.bretagne.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Etude_sur_les_densites_dans_le_Finistere_cle7b351c-1.pdf

[xvi] http://www.bretagne.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Etude_sur_les_densites_dans_le_Finistere_cle7b351c-1.pdf

[xvii] https://www.liberation.fr/debats/2020/04/03/la-ville-protege-t-elle-des-epidemies_1784045

[xviii] https://www.aurm.org/uploads/media/f7018dfe821c61135f2016a5d277c984.pdf

[xix] Cécile Féré, « Villes rêvées, villes durables ? », Géocarrefour [En ligne], Vol. 85/2 | 2010, mis en ligne le 09 janvier 2010, consulté le 07 avril 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/geocarrefour/7478

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Helsinki : Planning innovation and urban resilience

Death and life of CBD

Is resilience useful?

Long live urban density!

Behind the words: Recovery

Sending out an SOS

The ideal culprit

Behind the words: telecommuting

Behind the words: urban congestion

Behind the words: food security

180° Turn

Cities in safe boot mode

Behind the words: Affordable housing

Across cities in crisis

A street named desire

“Dig, baby, dig”

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.