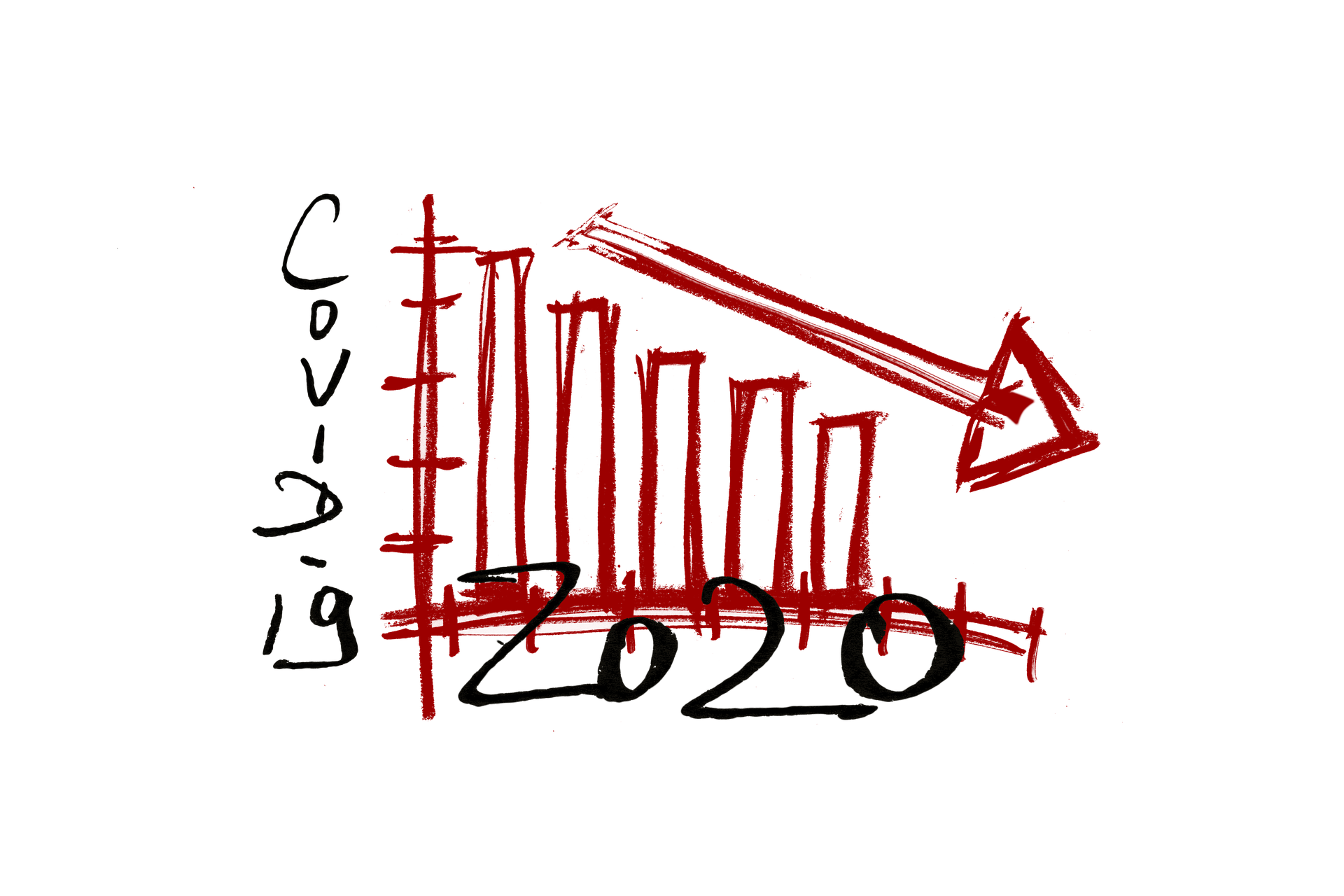

If the topic of food security did not emerge earlier in the North, it is also because it has long been a concern associated to cities of the Global South. Dependence of developing countries on food imports has accelerated since the 1980s, due to massive urbanization, specialization in crop production and structural reforms which led to the plummeting of domestic food production. In 2007-2008, a global food crisis, originating from a sharp rise in the price of basic food staples (wheat, rice, soybeans, corn), plunged some countries of the South into a state of political crisis and instability, particularly in North Africa (one of the factors that sparked the Arab Spring protests). This major crisis contributed to the repositioning of food security at the top of the global urban agenda and created renewed interest for urban food policies among the academic community.

The Economist Intelligence Unit, in its latest 2019 Global Food Security Index [12], underlines the vulnerability of countries dependent on food imports, given the growing consequences of climate change. Singapore, for instance, which has ranked at the top of the overall index in 2018 and 2019, drops 11 places when adding in the natural resources and resiliency metric, as a result of factors that include vulnerability to sea level rises, ocean eutrophication, and food import dependency. Today, food vulnerability no longer affects only the countries of the Global South but is shifting to the North, which creates new concerns and opens up a new phase in the city/food relation history.