Behind the words: Recovery

While it may not be over, the health crisis linked to the coronavirus epidemic now seems to be under control in most European countries. The time has come to draw up economic recovery plans capable of saving France, Europe, and the world from the economic and social slump into which they have been plunged by several weeks of frozen economic activity. National and regional economies are already being severely tested. The growth forecasts unveiled by the European Commission on 7 May 2020 reveal the extent of the disaster towards which the countries of the euro zone are heading: the Commission forecasts a 7.7% drop in gross domestic product (GDP) for the euro zone in 2020 (although this will be offset by an expected 6.1% growth in 2021). Along with Greece, Spain, and Italy, France is one of the euro zone countries where the recession is expected to be the most pronounced, with an expected decline in GDP of 8.2% this year. The International Monetary Fund expects a global recession of 3% in 2020, a situation it describes as “much worse than during the financial crisis of 2008-2009 [i]“. Unemployment figures are equally staggering: the much-anticipated monthly report of the US Labor Department, released on 8 May 2020, revealed that 20.5 million jobs had been destroyed in the United States in April alone, and it is not yet certain which proportion of these job destructions will prove temporary; in France, the IMF forecasts an increase in the unemployment rate of nearly two points, from 8.5% in 2019 to 10.4% in 2020. The economic crisis is on its way, and with it, its procession of bankruptcies and layoffs.

In this context, the word “recovery”, which refers to a policy aimed at creating a recovery in economic activity by promoting consumption or investment, is on everyone’s lips. Interestingly, compared to other crises, neither the principle nor the means of this recovery are debated: all countries, even those described as liberal, are mobilizing the public authorities to support and the economy and get it moving as soon as possible, with the support of central banks, in unprecedented proportions. The real issue at stake with this recovery is qualitative: what are we going to do with the money injected into the economy when the question – at least right now – is not so much how to find the money but rather how not to make mistakes in what we do with it?

Behind the word “recovery” lies a series of decisive choices that governments will have to make in the weeks and months to come. A first choice pertains to the link between the recovery and the environmental transition, at a time when all attention and resources are focused on the immediate survival of heavily strained economies and the containment of what promises to be massive unemployment. The second choice concerns the sequencing of the recovery, when the crisis is both a supply shock, due to the sudden and almost total halt of activity in many industries (mobility, tourism, leisure, etc.), and a demand shock – households are not mistaken, as shown by the explosion of the savings rate. A third choice, less discussed, concerns the scale of stimulus measures. Beyond the major sectoral support plans, the question of the right scale of action needs to be asked.

The economic crisis, a considerable risk factor for the ecological transition

The dramatic decline in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as a result of the economic downturn and lockdown measures is a one-off event that does not change the dynamics of growth in atmospheric emissions in any way. “The 30% decrease in CO2emissions observed during containment is not to be counted on. It is not sustainable because it is not the result of a structural change,[ii]” notes Corinne Le Quéré, President of the High Council for the Climate. What is more, the world with coronavirus could lead to an even greater increase in greenhouse gas emissions, particularly CO2.

In a context of persistently low oil prices, a certain number of countries may be tempted by a “grey” recovery, while the low cost of fossils may mean an increase in household purchasing power in the absence of high taxation on this energy source. Some may argue that the sharp drop in electricity production due to the near stoppage of industrial activity as well as the reduction in residential consumption, is just as much in favor of increased use of electricity and could encourage the electrification of uses (mobility, heating). The price of electricity has collapsed on the markets, particularly in the context of European overcapacity. The problem is that, in the European context, and more particularly in France, not only will households see nothing of this fall, but falling prices on the markets could even lead to an increase in households’ electricity bill. The rules governing the remuneration of investments on the networks, made necessary in particular by the increase in intermittency linked to renewables, are the direct cause of this [iii]. At the same time, the spectacular fall in electricity prices is massively increasing the cost of supporting renewable energies at a time when the resources earmarked for their development are shrinking. With a state-guaranteed feed-in tariff of around €70/MWh (average value for wind power) and a market price of €55/MWh, the cost of support is normally €15/MWh. But with a market price of €20/MWh, this differential increases to €50/MWh [iv]. Additionally, the revenue from the domestic tax on petroleum products (TICPE), part of which is channeled towards renewable energies, is in free fall. It is therefore both supply, via investment capacity, and demand, via purchasing power, that are being hit hard.

As far as mobility is concerned, the fear of contracting the Covid-19 will lead to a massive shift towards the private car, whatever the progress of alternative modes or teleworking: it is illusory to believe that the disaffection for public transport will be totally compensated by the disappearance of part of home-work commutes thanks to teleworking and cycling. The mobility data site proposed by Apple is spectacular in this respect: while it shows that mobility has not at all returned to its pre-lockdown levels, even more striking is the spectacular fall in the use of public transport around the world. On the other hand, the car is much more resilient and has even, in places like Germany, returned to levels that are close to normal. This change in mobility behavior is likely to continue as long as the pandemic has not been curbed, and even beyond, by virtue of the well-known hysteresis effect. Already exhausted, the public transport economy is undergoing a massive and unprecedented crisis that could lead, in many cities, to the outright elimination of part of the service offered. Yet in the heart and close outskirts of our cities and metropolises, public transport has been conceived as the backbone of the mobility system.

What does “green recovery” mean, and what method lies behind the political slogan?

In a context where the survival of entire sectors of the economy is at stake, the disappearance of which would have major systemic effects, it is natural that the modalities of the recovery should be the subject of debate. It could be tempting for states to address the most urgent needs and to reduce the resources they devote to the fight against climate change, a threat that may seem more distant and remote today than the one posed to our societies by the coronavirus. In the face of the above-mentioned threats, however, this would be a short-sighted calculation with serious economic and social consequences. “Stimulus packages can kill two birds with one stone – putting the global economy on a zero-emissions trajectory – or they can lock us into a fossil fuel system from which it will be almost impossible to escape … They can be ‘grey’, reinforcing the links between economic growth and fossil energy and creating the risk of asset neglect … or ‘green’, decoupling emissions from economic activity,[v]” write Joseph Stiglitz and a group of economists in an article published by Oxford University Press.

Where there is a consensus on the principle of a green recovery, such as in the European Union, it is clear that this common understanding is not enough to exhaust the debate. First of all, the environmental imperative should not obscure the fact that, for a large part of the economic fabric, the choice is not about whether to be green or brown, but how to survive. In this respect, the roadmap presented by the director of the Circle of Economists, Jean-Hervé Lorenzi (in French), is worth reading in that it articulates the short-medium term (the next six months) with the long term: “The long term is not only about health or the environment, because we must give priority to two areas that are currently neglected: the solidity of the economic system and a public service worthy of the name, responsible and strengthened in its means. These are the two priority subjects before looking at the ecological dimension. It is after the restoration of the economic system and public service that the growth model can evolve towards more ecological and environmental concerns. Let us not confuse priorities and emergencies. Let us not forget that in the short term we are going to be faced with the disappearance of thousands of businesses and massive unemployment. Let us avoid the hemorrhage, let us strengthen both our legs: the economic system and the public service. We can do this simultaneously. At the end of the year we will then be able to reflect on our new growth model, which will not be efficient and sustainable if our base is not consolidated. In the order of priorities that must be spread out over time, let us first resolve the social crisis, then rebuild a solid base and then think about a new growth model“.

Methods and tools are as much under debate as the sequencing of actions. As Christian Gollier points out, “the capacity of states to subsidize the transition has diminished. This action will have to be limited to financing the public infrastructure needed to coordinate private actions, households and businesses. We must be honest and recognize that public support for private transition efforts is mortgaged.”. The director (and co-founder, along with Jean Tirole) of the Toulouse School of Economics pleads for an immediate carbon tax at 50 euros. In fact, the effectiveness of direct state support mechanisms for a given sector is not guaranteed, either in ecological or industrial terms. In this respect, the increase in the premium for the purchase of an electric vehicle today means de facto support for the Chinese battery industry, which is extremely CO2-emitting. Even though France’s almost carbon-free electricity mix ultimately reduces CO2emissions, no one can deny the ecologically and industrially limited nature of this type of measure in terms of the public investment made. On the contrary, a carbon tax sends a price signal and has long-term effects that profoundly modify the technological and industrial fabric.

Thinking and spending on the right scale for an effective recovery

While the G20 has committed to “an inclusive and environmentally sustainable recovery” and the OECD has made a similar call [vi], the fact remains that a green recovery will only be effective if policy-makers manage to”think and spend at the right scale, i.e. by designing stimulus policies that are territorialized, tailored to the issues at stake, which are clearly spatialized, and by investing available financial resources at the right scale, as needed. Cities and territories will thus be at the forefront of post-Covid-19 economic recovery, and “will be, even more than before, the bridgehead of the transition, accelerating efforts to reduce pollution and overtaking States that are not always up to the task [vii],” writes Marc-Antoine Eyl-Mazzega, Director of the Energy and Climate Centre of the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI).

This question of scale leads to the no less important question of stakeholder networks. It is on the alliance between cities and territories on the one hand and, on the other, citizens who are now aware of the urgency of the environmental and energy transition that the success of the recovery will depend.

This territorial approach is at the heart of the decarbonization of mobility, as shown in our report on financing mobility, published on 28 May in French (English version forthcoming). In it, we show that this approach is all the more justified since mobility practices and uses vary greatly from one territory to another, depending on its characteristics, and that mobilities have a variable effect on the climate depending on the territories in which they are deployed. The interest of a territorialized perspective is obvious when we know that the mobilities between the peripheries and the center, the most GHG-emitting ones, are still forgotten in mobility policies. The identification of the relevant scale is therefore a sine qua noncondition for the effectiveness of public spending.

As far as buildings are concerned, while Bruno Le Maire recently announced that the recovery would involve investments in the thermal renovation of buildings, the observation is also true: it is at the scale of the block, i.e. of a group of buildings and the public space surrounding and crossing it, that an efficient energy renovation plan must be focused on. Current rates of building renovation, which average 1% per year, should at least triple. Simply increasing the resources devoted to this work will not be enough: accelerating renovation requires a new way of approaching the subject by first of all integrating a multi-building approach, in order to maximize the effects of the differences in the pace of life, which lead to different consumption profiles of buildings depending on the time of day, the days of the week and even the seasons. In addition, public space and the multiple networks it houses must be integrated into the equation. In the 21stcentury, a roadway, a pavement are strategic spaces where heat can be stored, for example: the innovations are there, which must be integrated into ambitious and visionary projects. Rather than reasoning on a building by building basis and spending massive amounts of public money for lack of a profitable model, let us reason more broadly, systemically, on the right scale and with multiple actors. Such an approach would also have the advantage of allowing for a more peaceful debate, moving away from the landlord-tenant face-to-face where time horizons, and therefore interests, may diverge. By integrating the public space, energy renovation projects lead to talking to the citizen and his representatives as well, thus becoming projects for the ecological transition of neighborhoods. Such a change in approach implies reasoning no longer by norm but according to concrete objectives, integrating system effects. It makes it possible to move away from a quantitative logic by maximizing the effect of each euro invested.

This is to say that it is not only a less carbon-constrained world that needs to be built for future generations, but also a less indebted world. Sustainable development, which is unfortunately all too often forgotten, has a dual component, environmental of course, but also economic. As the world prepares to face the most formidable economic crisis in decades, it is high time to remember this.

[i] https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020

[ii] https://www.actu-environnement.com/ae/news/rapport-HCC-climat-sante-covid-relance-35362.php4

[iii] https://www.usinenouvelle.com/article/covid-19-huit-chiffres-pour-comprendre-l-impact-du-confinement-sur-le-reseau-electrique.N955811

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Will COVID-19 fiscal recovery packages accelerate or retard progress on climate change? Cameron Hepburn , Brian O’Callaghan , Nicholas Stern , Joseph Stiglitz, Dimitri Zenghelisi

[vi] https://www.ifri.org/fr/espace-media/dossiers-dactualite/compatibilite-mesures-de-relance-laccord-de-paris-evaluation

[vii] https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/edito_maem_covid_energie_2020.pdf

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Is resilience useful?

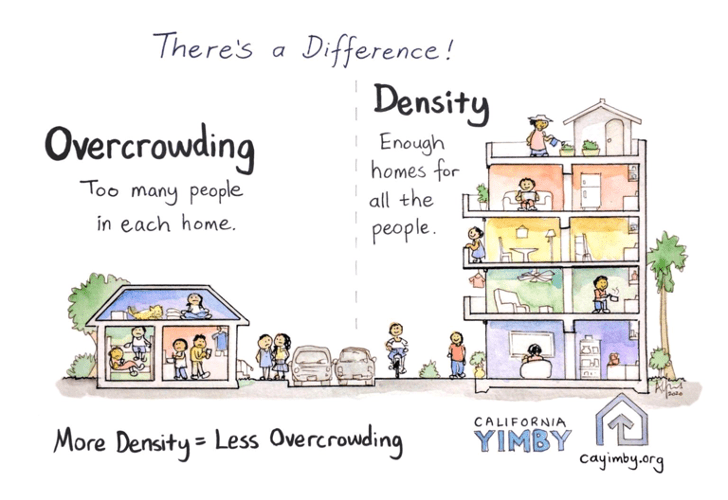

Long live urban density!

Sending out an SOS

The ideal culprit

Behind the words: density

Behind the words: telecommuting

Behind the words: urban congestion

Behind the words: food security

180° Turn

Cities in safe boot mode

Across cities in crisis

Behind the words: Degrowth

A street named desire

Feeding and fueling the city

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.