Behind the words: telecommuting

At the beginning of March 2020, well before containment measures were taken by public authorities in the U.S. and Europe, the increased risk of COVID-19 contamination led some of Silicon Valley’s main companies, namely Facebook, Apple, Tesla and Google, to encourage their employees to work from home as a precautionary measure [1]. Nearly a million people have been working from home in the San Francisco Bay Area, turning the global center for tech companies into an open-air laboratory for what mobility would be like if remote working was the norm.The reduction of the number of trips led to an 18% decrease in traffic [2] at rush hour between 2 and 8 March on the Dumbarton Bridge that connects the eastern part of the Bay Area to Palo Alto, the heart of the Silicon Valley. The pioneering approach taken by tech companies has since become the norm everywhere else with the enactment of lockdown measures in early April 2020 [3].

Telecommuting is often linked to various promises, especially in terms of mobility, which will be the main focus of this paper. Working from home is praised for its ability to suppress work-related trips, which accounted for a little less than 20% of total daily trips in 2010 in France [4].Applied at a large scale, telecommuting could theoretically allow a significant reduction in daily flows, thus fueling public authorities’ ambition to reduce urban congestion and negative externalities linked to these trips.

To what extent can the spread of teleworking help solve certain mobility issues, such as urban congestion and CO2emissions? Does the reduction of commuting trips mean an overall reduction in mobility?

What does “working from home” mean?

It would be wrong to think that the concept of working from home came about thanks to progress in communications technology and the invention of the Internet. As early as 1950, Norbert Wiener, an American mathematician considered to be the father of cybernetics, mentioned the possibility of working remotely.He took the hypothetical example of an architect living in Europe and actively supervising the construction of a building in the United States using a technology that would allow him to send and receive messages quickly: the Ultrafax[5].

It took twenty years for the concept to gain relevance thanks to decades marked by various decisions and events that made the idea of optimizing travel, especially between home and work, more credible:

- In the United States, the 1970 Clean Air Act (CAA) gave the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the responsibility to control and set limits on CO2emitted from fixed or mobile locations[6];

- The term “gridlock”[7]appeared in the vocabulary of traffic and urban experts to describe the chaotic traffic jams that paralyze American cities every day, especially New York City. The regular paralysis of roads is described as a vector of negative externalities such as CO2and fine particle emissions[8];

- Finally,the first oil shock of 1973 affected the American economy and led to a significant increase in gasoline prices at the pump. It encouraged motorists to reduce their fuel consumption.

These decisions and events fueled reflections about the possible optimization of daily trips. In 1973, Jack Nilles, a former NASA engineer, developed the idea of an alternative to daily commuting: thus, telecommuting was conceptualized for the first time. The idea was to work without commuting from home to work. Three year later, in his book The telecommunications-transportation Tradeoff: options for tomorrow(1976), Nilles laid the groundwork for what he called teleworking, the possibility of working remotely. Subsequently, several words became commonly used to describe this new practice[9]. We now speak of teleworking, telecommuting, flexiworking, distance working, remote working, working from home, etc. These terms all refer to the possibility “to work periodically in a different place from the usual workplace, one or more days every week, from home, at a client’s workplace or in a dedicated place”[10]. For Nilles, teleworking could lead to a decrease in travel demand and, therefore, reduce traffic congestion and CO2emissions[11].

While this link is logical, should it allow us to conclude that telecommuting is an effective strategy for reduceing traffic congestion in cities and decarbonizing mobility in a sustainable way? For the time being, despite the massification of information and communication technologies (ICTs) and in particular the Internet, telecommuting is barely taking off. In France, in 2019, according to the French direction of the animation of research, studies and statistics (DARES), 3% of employees are working from home at least one day per week, with a higher rate among managers[12].

As promising as it is for travel demand, telecommuting remains a minor reality outside of the crisis we are going through. How can we explain this paradox?

An optimization of the activity program

What if the problem was a misconception of telecommuting? For Anne Aguiléra [13], Virginie Lethiais [14], and Alain Rallet [15], the social expectations that have constantly come with telecommuting have ended up giving it a role that does not suit it. Indeed, since its origins, working from home, as it was often called “telecommuting”, has been presented as a substitute for travel. For the authors, this perspective is a mistake that needs to be corrected by adopting a new perspective on telework.

Maybe it is finally time to consider telecommuting not as a tool for reducing overall commuting, but rather as a means to better manage individual mobility [16].

Jean-Marc Offner’s [17] definition of mobility as “the space-time of activity program”[18] shows that the objective of telecommuting is twofold. On the one hand, it allows individuals to act on their location system by making the place where they live, or another place, coincide with the place where they work. On the other hand, as a consequence of this action, they reduce, or even eliminate, their need to commute. From this definition, it is clear that the primary objective of telecommuting is not to reduce mobility, and with it, its externalities, but rather to optimize an individual activity program.

According to a CSA Research study for Malakoff Humanis [19], employees’ main motivations for telecommuting are the reduction, or even the suppression, of their commute (46%), but also the ability to plan working hours at their will (39%) and to better reconcile professional and personal life (37%). According to Yves Crozet [20], teleworking appears to be a solution to hypermobility [21] by allowing to reduce mobility at an individual level and thus helping people to live in a familiar environment with personal anchors.

However, the optimization of activity programs, by reducing commuting trips, does not exclude an increase in travel demand for other reasons, thus creating negative externalities linked to these new trips. Through a rebound effect [22], the beneficial consequences of telecommuting on the externalities linked to motorized travel can be blurred or even cancelled [23]. Indeed, the optimization of an activity program through the suppression of commuting trips can help people engage in other activities which can, in the end, generate additional trips. This rebound effect will be more or less significant depending on whether individuals use the travel time saved to do their groceries or to go on a weekend trip hundreds of kilometers away. For example, in 1998, in the United States, telecommuting led to a reduction of the total number of vehicle-miles traveled (VMT) by… 0.79% [24]. Although telecommuting appears to be an economically efficient way to reduce travel, its effect on the reduction of VMT is minor. The COVID-19 crisis, while being a large-scale test for how things would look with a large number of employees telecommuting, does not show the real effects of telecommuting on mobility and the possible rebound effects, since it has come with a ban on non-essential trips.

Shifting perspectives: the challenge of organizing telecommuting

This shift in perspective regarding telecommuting is essential. It raises an important question: how can we make telecommuting a more common practice in order to make it an effective lever for coping with the negative externalities caused by mobility? How can telecommuting be brought into the era of massification?

The answer is simple… at least on paper. We must change scale in the conception of telecommuting and consider it no longer at the individual level or the company level, but rather at the territorial scale. Following this logic, different actors of the Toulouse living area – the metropolis, companies (Airbus, ATR, etc.) and the transportation authority (Tisséo Collectivités) – have gathered around the European project DEMETER. One of DEMETER’s components is “COMMUTE”, a project dedicated to mobility. COMMUTE aims to design a new urban mobility model for the territory surrounding the Toulouse Blagnac Airport. The attractiveness of this zone generates a large number of trips, mainly by car (83%). The consequence of these trips is the recurrent congestion of the road network and the large share of road traffic in CO2emissions. Within the Urban Innovative Actions (UIA) project [25], the different partners involved with COMMUTE aim to test various solutions to reduce congestion episodes in the aeronautical zone [26]. One of the identified levers is to organize telecommuting on the scale of the business cluster and optimize modal shift to collective modes [27]. To this end, the project aims to set a joint commuting policy [28] (Plan de déplacement d’entreprises, PDE) that will be shared by all the stakeholders of the areadifferent company commuting policies in order to make it a lever not only for optimizing mobility at the individual level but also at the regional level.

We must look closely at this innovative initiative. Yet its very nature encourages us to draw a first lesson: unlike what we are experiencing with strict containment measures, which can be seen as imposed telecommuting in a top-down and national logic, telecommuting, in order to act on travel patterns on the long run, must be organized following a triple logic that should be local, partnership-based, and centered on real behaviors and practices. Local, meaning centered on the living area, putting administrative or company branch logics aside. Partnership-based, because it should take into account the different stakeholders. And centered on behaviors, because a thorough understanding of work and mobility habits must be fully part of the equation.

In other words, to make telecommuting an effective lever to reduce mobility demand takes time, the time required for experimentation and negotiation. This means that it will be difficult to apply uniform solutions onto different territories. This represents an important challenge for companies’ organization which, additionally, should be given a role in the reorganization of mobility beyond the financial logic of taxation to finance mobility.

[1] Mark Gurman, Apple encourages Silicon Valley staff to work from home due to coronavirus, Forbes, 6 March 2020. [URL: https://fortune.com/2020/03/06/apple-coronavirus-remote-work-wfh-silicon-valley-staff/]

[2] In number of cars.

[3] In France, according to a survey conducted by CSA Research for Malakoff Humanis in March 2020, periods during which mobility is strongly impacted, such as strikes or an injunction to social distancing, favors the development of working from home practices. In France, the strikes in December 2019 led to an increase of telecommuting: almost 50% of employees worked from home regularly (35% when Paris region is excluded), 4% were telecommuting exceptionally and 6% could work from home. In other words, 40% of French employees and 60% of Paris region employees could work from home.

[4] Jean-Marc Zaninetti, Les déplacements domicile-travail structurent-ils encore les territoires ?, MappeMonde, September 2017.

[5] United States Department of Transport, Transportation Implications of Telecommuting, April 1993.

[6] Lincoln County, Air Pollution and Traffic Congestion, Lincoln County. [URL: http://www.lincolncounty.org/DocumentCenter/Home/View/774].

[7] Traffic jam.

[8] James Gleick, National gridlock: Scientists tackle the traffic jam, The New York Times, 8 May 1988. [URL: https://www.nytimes.com/1988/05/08/magazine/national-gridlock.html?pagewanted=all].

[9] Paul J. Jackson, Jos M. van der Wielen, Teleworking: New international Perspectives FromTelecomuting to the Virtual Organisation, Routledge, 2002.

[10] Murugan Anandarajan, Claire Simmers, Managing Web Usage in the Workplace: A Social, Ethical and Legal Perspective, Idea Group Inc (IGI), 2003.

[11] Sangho Choo et al., Does telecommuting reduce vehicle-mile traveles? An aggregate time series analysis for the U.S., Transportation, 2005.

[12] DARES, Le télétravail permet-il d’améliorer les conditions de travail des cadres ?, 4 November 2019. [URL: https://dares.travail-emploi.gouv.fr/dares-etudes-et-statistiques/etudes-et-syntheses/autres-publications/article/le-teletravail-permet%E2%80%91il-d-ameliorer-les-conditions-de-travail-des-cadres].

[13] Deputy director of the « Planning, mobility, environment » department Gustave Eiffel University.

[14] Lecturer in economy at the IMT Atlantique (former Telecom Bretagne)

[15] Professor Emeritus in Economic science at the University Paris-11 Sud and member of the laboratoire d’économie-gestion « Réseaux innovation, territoires et mondialisation » (RITM).

[16] Anne Aguiléra & Virginie Lethiais, Alain Rallet, Le télétravail : sortir de l’impasse, Métropolitiques.eu, 8 December 2014. [URL: https://www.metropolitiques.eu/Le-teletravail-sortir-de-l-impasse.html] (Consulté le 8 avril 2020).

[17] General director of the Bordeaux Metropolis’s planning agency (A’urba).

[18] Interview of Jean-Marc Offner, General director of the Bordeaux Metropolis’s planning agency (A’urba) realized by La Fabrique de la Cité in 2017 [URL: https://www.lafabriquedelacite.com/publications/repenser-les-mobilites-du-quotidien-jean-marc-offner/]

[19] CSA Research, Étude Télétravail 2020, Regards croisés Salariés / Entreprises, 3e édition, Malakoff Humanis, 12 March 2020. [URL : https://newsroom.malakoffhumanis.com/assets/synthese-etude-teletravail-2020-2a13-63a59.html?lang=fr].

[20] Julie Colin, Se déplacer pour mieux s’enraciner : le paradoxe de l’hypermobilité, InMovement, 26 July 2019. [URL: https://www.inmvt.com/fr/eclairage/se-deplacer-pour-mieux-senraciner-le-paradoxe-de-lhypermobilite/].

[21] Hypermobility is defined as the increase of commuting distances allowed by the increase in travel speeds.

[22] A rebound effect is defined as the situation when the environmental gains made possible by energy improvement or by a better optimization of uses are canceled by behavioral modifications inducing additional emissions.

[23] AFP, Le télétravail, un outil de lutte contre la pollution à apprivoiser, Le Point, 20 June 2019. [URL: https://www.lepoint.fr/societe/le-teletravail-un-outil-de-lutte-contre-la-pollution-a-apprivoiser-20-05-2019-2313604_23.php#].

[24] Sangho Choo et al., op. cit.

[25] L’Urban Innovate Actions (UIA) is a European initiative that allows to urban areas in to set innovative solutions to cope with the challenges they face.

[26] Toulouse Métropole, Airbus, Région Occitanie, Le 1er engagement territorial pour la transition énergétique, Plaquette de présentation du « Démonstrateur des engagements territoriaux pour la réduction des émissions », October 2017. [URL: http://www.cdc-biodiversite.fr/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Projet-Demeter-Dossier-de-Presse-v3.pdf].

[27] Aurélie de Varax, Mobilité urbaine. L’Europe financera le projet Commute de Toulouse métropole, Touléco-green.fr, 10 October 2017. [URL: http://www.touleco-green.fr/Mobilite-urbaine-L-Europe-financera-le-projet-Commute-de,22873].

[28] Aurélie de Varax, Coup d’envoi du projet Demeter sur la zone aéroportuaire de Toulouse, Touléco-green.fr, 5 October 2017. [URL: https://www.touleco-green.fr/Coup-d-envoi-du-projet-Demeter-sur-la-zone-aeroportuaire-de,22816].

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Death and life of CBD

Is resilience useful?

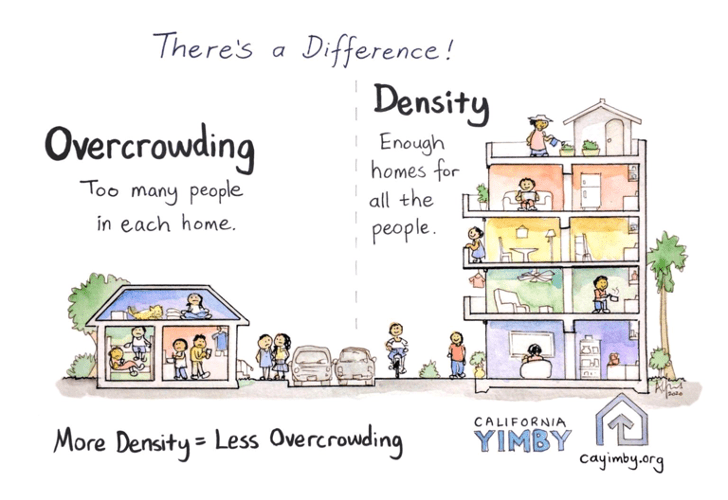

Long live urban density!

Behind the words: Recovery

Sending out an SOS

The ideal culprit

Behind the words: density

Behind the words: urban congestion

Behind the words: food security

180° Turn

Cities in safe boot mode

Across cities in crisis

A street named desire

The political and technological challenges of future mobilities

Inventing the future of urban highways

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.