Building affordable housing in London: utopia or project?

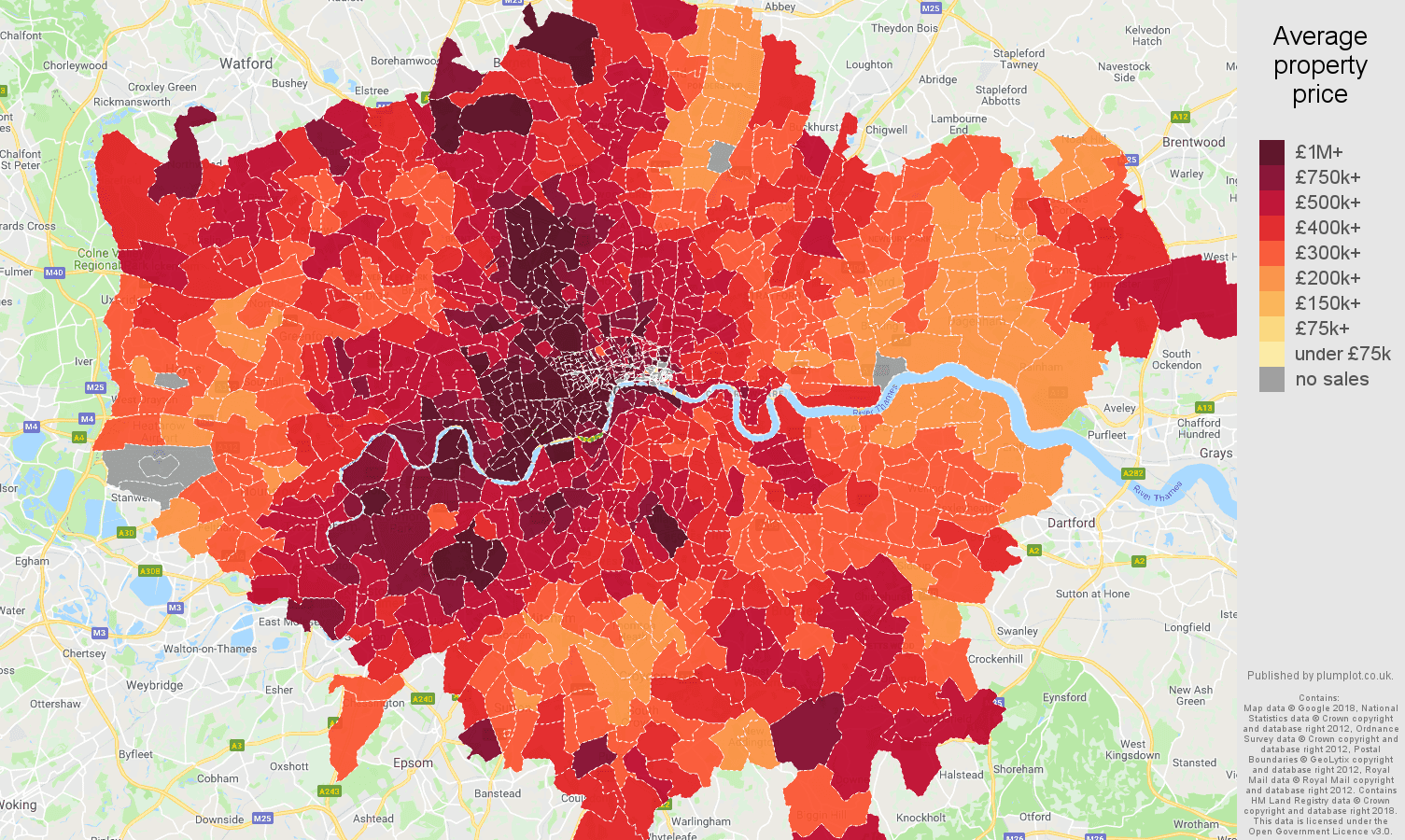

“Londoners know better than anyone that our city is in the grip of a major housing crisis – they live with the consequences every day”, wrote Sadiq Khan in October 2017 in an opinion piece published in the British daily newspaper The Guardian[1]. London has been one of the most expensive European capitals for many years, and while purchasing a home currently costs a UK inhabitant 7.77 times their annual earnings, a Londoner would have to spend 13.24 times the average earnings figure to hope to purchase housing in the British capital[2]. This situation stems from the UK’s adoption in the second half of the 20th century of a policy which actively incited homeownership, supported by favourable tax treatment and access to credit.

From simply being a place to live, housing has become the critical component of an asset-building strategy in preparation for retirement for British households. “Many UK households now have a personal interest in the maintenance and further growth of prices”[3]. Against a backdrop of soaring housing prices in the UK., it is paradoxically difficult, on a political level, to come up with strategies with the clear aim of driving down prices. This shift to considering housing as an asset is in itself a factor behind rising property prices: “The problems of affordability, which so many cities and rural areas now confront, stem from the fact that the inherited stock of housing changes hands as assets, at prices which bear no relation to original costs of building or the costs of replacement”[4]. A very pronounced decline in the production of public housing bringing construction to a standstill, compounded by policies to sell such housing to occupants (Right to Buy, see below), completes the picture.

In the 1950s, housing in the UK cost on average four times the average annual salary. By 2008 this figure had jumped to eight. In addition to price increases, these statistics demonstrate a stagnation in income which, together with the increasing consideration of housing as an asset, fuelled growing inequalities which are now concentrated along a generational axis. The baby boomer generation, most of which are homeowners who have fully paid off their mortgage, are now enjoying relatively limited housing expenses and good housing conditions. This is still not the case for those under the age of 50: due to difficulties in becoming homeowners, young households are generally tenants (in private housing stock). If they are homeowners, they are obliged to repay their mortgages through hefty monthly instalments. Overall, their housing costs are much higher than those of baby boomers. It is estimated that the generation currently aged between 18 and 35 years will still not have purchased a home in 20 years and their ratio of income[5] will remain high.

In London, this trend indicates a constant decline in the homeownership rate since the year 2000, falling from 69.6% in 2002 to 63.6% in 2013[6]. Private housing stock is also becoming less and less affordable for low-income households (in particularly of younger generations), while at the same time their income is not increasing as quickly as property prices[7]. Some people can therefore no longer house themselves in the market sector due to inadequate income (salaries or pensions), rising house prices and the regional imbalance of supply and demand[8]. In many cities, the private rented sector has consequently become the only source of housing both for those who would have preferred social housing and many who had hoped to buy[9]. In 2014, private rented housing accounted for 17% of the total UK housing stock.

London, a victim of its own popularity?

The population of the UK capital rose by more than 27% between 1991 and 2016 and is set to reach 10 million by 2030[10]. Fuelled by an attractive labour market and London’s economic dynamism, this demographic growth has also led to an increased demand for housing, which the slow developing existing residential stock is struggling to meet. In London, housing stock has only grown by 8.5% since 2006 – i.e. only around 65% of the growth in household numbers and 50% of the growth in population over the same period[11], while only 24,180 new units were completed in 2016 when population projections suggest that a minimum of 50,000 units need to be built annually just to meet demand[12]. “London has been very successful at creating jobs,” explains James Murray, Deputy Mayor for Housing and Residential Development, “and relatively unsuccessful, in fact a failure, at building homes. In the last 20 years, jobs have gone up by about 40% in London, but the number of homes has gone up by 15%”.

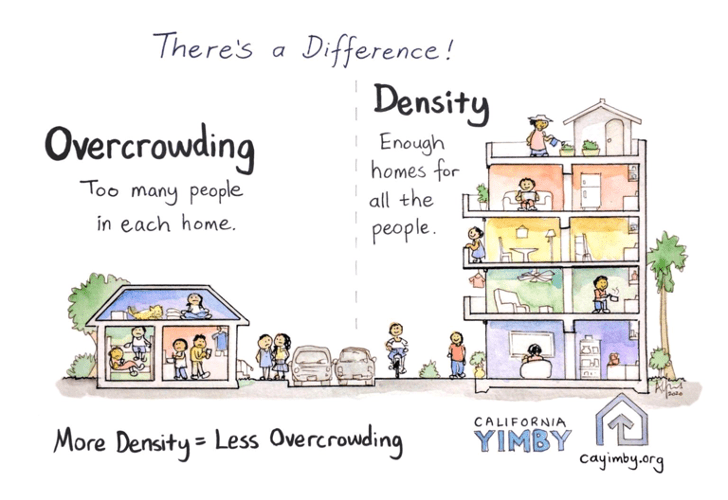

An overlapping of physical and regulatory restrictions weighs down the housing supply in London, and is the cause of the slow development of the city’s residential stock. The first of these restrictions is topographical: “all major cities are surrounded by massive green belts, so London cannot grow horizontally,” explains Christian Hilber, professor at the London School of Economics. This is compounded by the regulatory limit concerning the height of buildings in most London boroughs. The capital therefore cannot expand horizontally or vertically, and “if the housing can’t expand, then prices go up”, notes Christian Hilber. Another regulatory constraint is the requirement to protect heritage buildings, which hinders the development of housing supply in London: “In Westminster, 98% of all land is developed. Let’s say 2% are public parks. Essentially the only way to add housing is by knocking down a building at higher density, which is extremely difficult in Westminster because almost everything is preserved”, states Christian Hilber.

These regulatory and physical limitations prevent housing supply from rising to a level which would enable it to meet the soaring demand: “The shortage of affordable housing results from an imbalance between supply and demand. London being a very attractive city means demand is exceptionally high, and the UK has a long-term supply problem”, explains Luke Murphy, Associate Director for the Energy, Climate, Housing and Infrastructure Team at the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR). Christian Hilber confirms: “The main reason behind the shortage is about supply and demand. London is one of the few superstar cities in the world. It’s a very desirable place to be for many high-skilled people. The question of whether this demand will lead to extremely high prices and rents depends on whether or not it is easy to create supply, whether it is possible to add housing”. Housing prices, which are at the intersection between supply and demand, are what they are today because the demand for housing has the specific characteristic of being highly inelastic – nobody would agree to go without it, even at a significant financial cost. This means that, in a housing market such as in London where there is low supply and high and growing demand, the equilibrium price is clearly particularly high.

This simple economic statement is the root of a number of trends observed in London, often cited as evidence of the housing crisis: the increasing number of adults per household, indicating that some adults are living longer with their parents, the decrease in the average surface area per person, the clear rise in households’ ratio of income and the increased average age for first-time buyers, all demonstrate growing difficulties when purchasing a home. Another consequence of the rising prices and the shortage of affordable housing is the vacancy rate which is virtually zero, indicating an almost perfect alignment between the number of existing housing units and the number of households, depriving the housing market of the variable for adjustment which allows it to operate effectively[13]. These trends were exacerbated by the 2008 financial crisis: property prices in London are now 50% higher than they were prior to the crisis.

This increase in property prices feeds into a vicious circle: “The very fact that property prices and rents rise relatively fast in some cities compared with others […] attracts more money from investors who speculate that the relative growth will continue. […] while it is hard to get an initial toe-hold in the London housing market, high levels of capital appreciation are anticipated by those who do and this may be a factor encouraging some to enter that market”, notes Foresight in a report published in June 2015[14].

The rapid rise in London’s land value

In London, the average value of land has soared in recent years, to the extent that, today, “the cost of land accounts for more than half of the cost of building a standard flat in a central London location, as opposed to around a quarter of the cheapest suburban equivalent”[16]. As building costs vary little from one London borough to another, land prices are the main variable for housing prices in the UK capital.

The “Hope Value” mechanism is among the factors behind this rise in land value. Luke Murphy explains as follows:

“If you’re a land owner, under the current system, you can expect what is called currently the ‘Hope Value’. If I have a piece of land, a field marked for agricultural use, and the local authority wants to purchase that piece of land to develop housing, it will have to pay me the value of the land as it is currently, plus something called Hope Value. If my land is worth £10,000 as a farm plot, it is worth £1 million as a plot to build housing on, and I can expect the local authority to pay me an amount closer to what it would be if I already had housing. Many countries have regulated land sale prices so that there is no Hope Value. In Germany, as soon as land is designated as somewhere for housing, it is frozen at the existing price”.

This mechanism, together with the perception of housing as an asset, contributes to the increase in London’s housing prices.

The GLA faces the land consolidation challenge

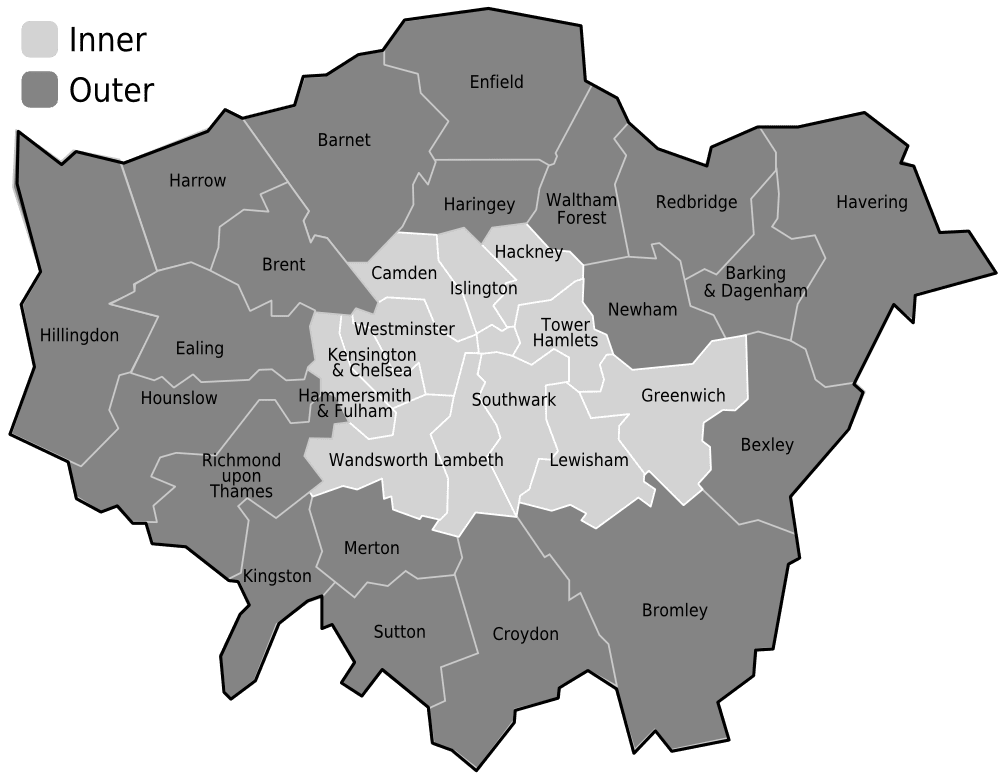

In addition to rising prices, land is also difficult to use. The Mayor of London has made this one of the focal points of his strategy and has announced his intention to conduct a policy which steps up interventions on the land market. He wishes to “intervene in the land market himself to secure land for a low enough cost that it can be economic to put up low-rent housing on it”, explains Kath Scanlon, researcher at the London School of Economics. The Draft New London Plan[17] does make the assertion of a sufficient land reserve in Inner and Outer London, to meet the estimated requirement of building 66,000 housing units per year, half of which would be affordable.

Yet a significant share of this land for potential development is owned by people who have no intention to sell, build on or convert their land: “What the Draft New London Plan calculations do not consider is who owns the land and whether they intend to build houses on it. Often, the answer is no. They have plans to use it for other things, they are in another business entirely, and they are not putting a lot of energy into optimizing their land value”, explains Kath Scanlon. Almost one quarter of London’s land is owned by public bodies[18] (nationally, 40% of brownfield sites[19] suitable for development are in public sector ownership[20]) for whom building housing is not necessarily a priority: “It is also understandable that active management of property assets to release land for others to provide homes is a low priority for organisations delivering public services. Quite simply, for the majority, managing property is an administrative function rather than a corporate goal, and building homes is not what they do”[21]. However, public authorities own many unused or under-used assets which could be “redeveloped to provide better public value”[22], in particular by building affordable housing. Yet several obstacles stand in the way of successfully implementing such a strategy, starting with the insufficient growth, by the various public bodies owning land, of their own assets.

A report by a team of researchers from the University of West England notes that:

“Council records[23] are not always complete and are, in some instances, wholly absent. Moreover, they only account for one part of the public sector. They do not, for example, touch on land or assets owned by the NHS [National Health Service] in London. Furthermore, such records do not account for land or assets still in use but underutilised, whether that is a part-occupied office block, decaying housing stock in need of renewal, or […] low-rise housing which could be redeveloped to provide more modern, high-density housing. Recent research has estimated that two million new homes could be built nationally on surplus public land. Of these, over 100,000 could be built on land owned by the Greater London Authority (GLA) group (including Transport for London)”[24].

The law does not oblige public bodies to disclose the list of land assets they own which are surplus to their own operational requirements. Moreover, there is no authority responsible for reviewing surplus assets or land belonging to public bodies to assess which plots may be sold to meet housing needs. Similarly, there is no authority responsible for identifying under-used assets and to implement the necessary measures to obtain greater value from them. The fragmentation of public landowners and their differing priorities[25] together with their poor knowledge of the assets they own are all factors to be resolved to enable the GLA to develop land identified in the Draft New London Plan and in a bid to grow the stock of affordable housing in line with the Plan’s sustained densification avenue.

Another reason why the GLA is struggling to develop land is because “the public sector has a very limited role in terms of assembling land, bringing forward land and unlocking the block sites”, regrets James Murray, for whom the GLA’s current authority is insufficient to meet the objective set in the Plan, which is appealing more for assistance from the British government. “The Mayor is quite clear that getting from around 30,000 housing units, where we are now, to 65,000 is not something which can be achieved just by dialling up the current model.

It requires us to support what is going now but have a complementary set of other approaches as well. It requires the national government to invest more money in infrastructure, and to give us greater powers for the public sector to build more homes directly. […] To get to 65,000 we’d need the government to help us change the rules of the game, with more investment, with greater formal land powers”, explains James Murray. Many people stress that the GLA should have greater powers in terms of land consolidation, arguing that its status as a major landowner gives it the necessary expertise to carry out this function.

In practice, these increased powers could include the identification of public land which is currently not utilised in its boroughs: “Government should empower the Mayor to identify the publicly owned sites in London – under the ownership of central government through to local government, including all public bodies – which are surplus to the public sector’s operational needs”, advises London First[26], which also recommends empowering the Mayor as the disposing agent for such sites.

Another obstacle to the building of affordable housing on London’s brownfield sites is boroughs’ control over development, which creates delays and unpredictability according to some experts. The GLA is therefore only the competent body to issue planning permission if the project under study involves the building of more than 150 housing units[27]. Smaller-scale projects are subject exclusively to the decision of the boroughs. There are 32 boroughs, in addition to the City of London, so therefore developers must deal with 33 different local authorities. This procedure “acts as a disincentive to entry into the London market for those seeking to invest in or develop housing”[28], in particular for small developers wishing to conduct business in several boroughs. Some therefore believe that the government should increase the Mayor’s powers in terms of issuing planning permission, leaving the boroughs with fewer powers, in order to simplify the current process and mitigate the risks carried by developers and investors when they undertake housing projects. London First stresses that “the Mayor is best able to balance the local interests of London’s different communities with the need of the city as a whole to see a substantial increase in housing supply. This suggests that the Mayor should either directly take more planning decisions over housing or be able to set tougher requirements on the boroughs”[29].

The Green Belt, an untapped land reserve

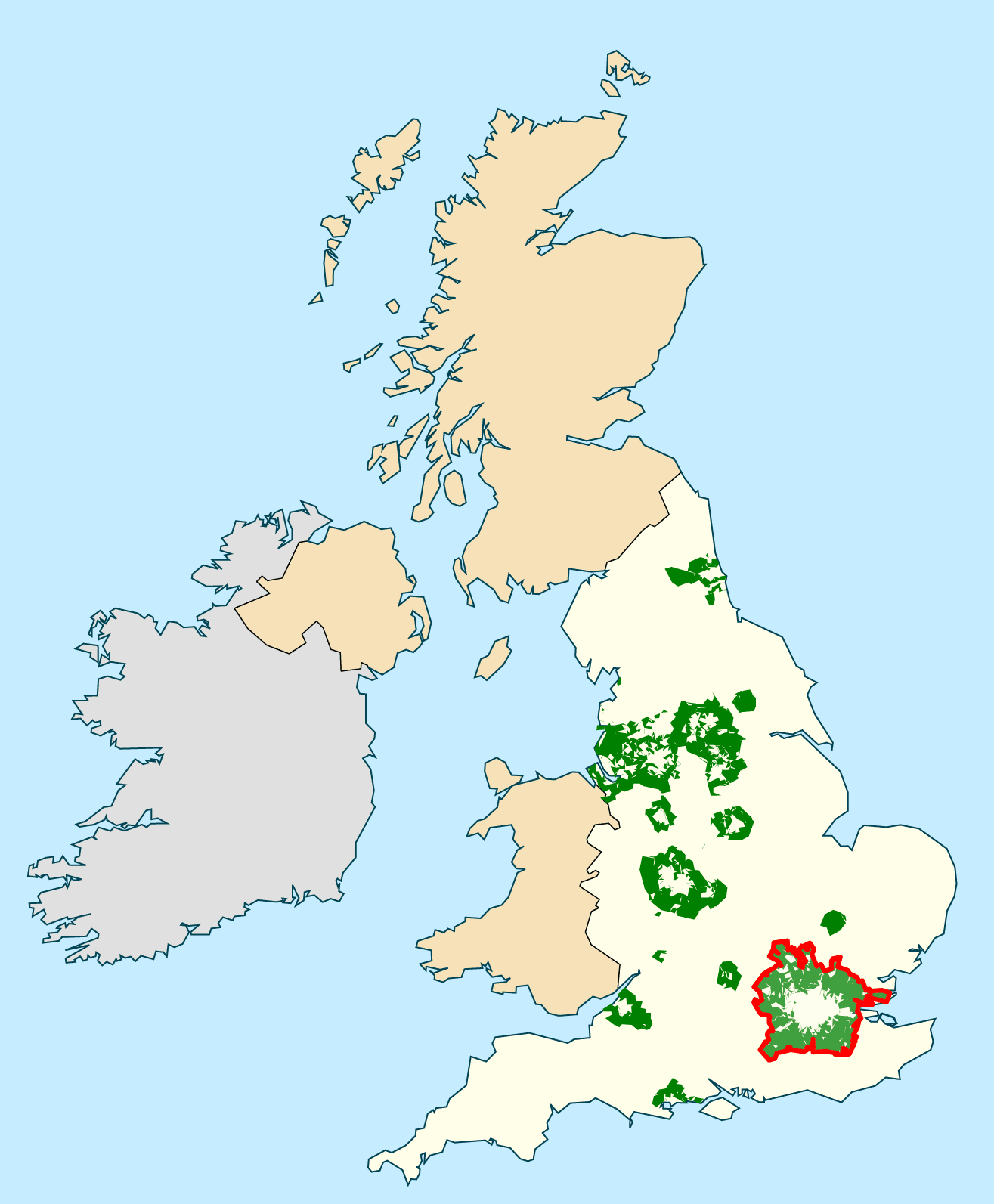

While the use of brownfield sites, the sustained densification strategy and the contingent attempts to optimise public land defended by the Greater London Authority will most likely allow London to develop its affordable housing stock, many experts agree that such efforts will not be sufficient to meet the announced annual housing production objectives, and that an additional measure – albeit controversial – is necessary: the use of Green Belt land around the capital. However, the Greater London Authority’s sustainable intensification strategy is based specifically on the renewed refusal to develop this Green Belt and to use the significant land reserve it represents. This refusal is probably motivated by the idea that London’s Green Belt is a green recreational area for the capital’s inhabitants, which is even more valued with the widespread perception of air pollution issues and the difficulties of living in a highly dense urban area. This does not mean that the current make-up of London’s Green Belt should not be considered. It is far from providing a breath of fresh air for Londoners, and its origins show that it was never designed for this purpose.

According to British researcher Paul Cheshire, the development of green belts was not a deliberate strategy, but rather an accident of history. In the 19th century, European cities did away with their city walls, as the “development of the nation-state and mechanised warfare had rendered them functionally irrelevant”[30]. For military strategy reasons, these walls were generally surrounded by an area deliberately kept clear. Their demolition, reminds Paul Cheshire, “released a substantial circular ring of space around the city. Bourgeoisie civic-mindedness was just developing. The map shows what was proposed: a Green Belt if ever there was one! But only a belt by accident. It was on the space released by the city walls and not surprisingly city walls had a roughly circular shape”[31]. In the United Kingdom, the creation of London’s Green Belt, rather than for environmental protection reasons, was the result of a proposal by Lord Meath, an Anglo-Irish philanthropist inspired by the example in Vienna who was convinced that cities “corrupted the gene pool of the British” and that their spread must be contained[32].

The idea was raised several times at the start of the 20th century and was finally enshrined in law in 1938 with the adoption of the Green Belt (London and Home Counties) Act, which gave local authorities the power to purchase land destined for public use. “By the late 1940s, 20,000 hectares of land had been bought around London dedicated as public open space”[33]. After World War II, a law provided green belts for any major city wanting one. This law remains the foundation of the current British planning system, explains Paul Cheshire, and it gave power to local governments to prevent urban development on as yet undeveloped land: “Privately-owned land, if designated as Green Belt, would remain private. While still promoted in the name of green space, in practice the Green Belt provisions in the 1947 Act just stopped anything happening – rather than creating valued recreational or open spaces”[34]. Although Green Belts were designed in 1947, they were only implemented as from 1955, under a Conservative government that changed their purpose: suddenly, “no more were Green Belts to be green lungs or recreational space; they were just to stop development”[35]. This is still their purpose in the 21st century; extending over 1,639,090 hectares[36] on a national scale today, green belts still have the primary objective of curbing urban spread. The National Planning Policy Framework states that “the Government attaches great importance to Green Belts. The fundamental aim of Green Belt policy is to prevent urban sprawl by keeping land permanently open; the essential characteristics of Green Belts are their openness and their permanence”[37]. Paul Cheshire considers green belts to be “a very British form of exclusionary zoning […], with the effect of confining the urban poor to live at high densities in the cities and preserving the Home Counties […] for the aspirant gentry who had got there earlier on the tracks of the suburban railway network”[38].

Today, the Metropolitan Green Belt around London extends more than 40 miles (60km) from the city; 94%[39] of it is outside the British capital. The remaining part of the Green Belt located within the city’s boundaries is in the boroughs of Outer London and accounts for 22% of all the land in the capital. By means of comparison, 27.6%[40] of London is covered by buildings, roads and railways. This provides a greater understanding of the huge land reserve that the London Green Belt represents within the city. It should also be noted that it is mostly privately owned and therefore inaccessible to the public. In addition, while the Green Belt’s environmental value is clear, it is limited to certain sites of specific scientific interest or habitats for protected wildlife species, which make up, with green areas open to the public, only 26% of London’s Green Belt[41]. The remaining land has a variety of uses: agricultural land (59%), airfields, water treatment plants, former hospitals, and golf courses[42] (the latter making up 7.1% of the capital’s Green Belt!). “I think it is being built up into the idea that all Green Belt land is rolling hills, beautiful. There is a kind of a myth over this land”, explains Luke Murphy.

Protecting the Green Belt (of which only 2% currently has buildings)[43] and the refusal to use it to unlock land for development which could create new homes are a conscious political decision made by London Mayor’s Office: “The argument that some have put forward that we need to build on Green Belt land, is one we do not accept, because we’ve identified the capacity on brownfield sites”, explains James Murray, Deputy Mayor for Housing and Residential Development. However, many observers see the Green Belt as one of the key elements in a strategy to meet the estimated annual housing demand. “If you calculate how many houses could you build in the vicinity of 800-metre walking distance from existing tube stations in the green belt, you could build about one million homes in the Greater London area alone”, explains Christian Hilber, Professor at the London School of Economics. “You’re not going to get there with brownfield sites alone”, he states, referring to the Mayor of London’s ‘Brownfield First’ strategy. The Green Belt’s potential to produce housing has been proven: 60% of it is within 2km of an existing rail or tube station[44], while 14 London boroughs, covering most of Outer London, have more land designated as Green Belt than is built on for housing[45].

Tom Papworth (Adam Smith Institute) stresses that “Green Belt policy imposes a strict limit on the supply of developable land around major urban areas. This constrains development and thus puts upward pressure on the purchase and rental prices of homes“[46], and argues that the pressure that the Green Belt system puts on housing supply has contributed to the extreme housing price volatility in the UK in the last 50 years. It is not surprising then that this point of the GLA’s policy is highly contested by urban planners and housing experts in London. “Excluding the possibility of development on highly connected or degraded greenbelt sites could result in decisions that run counter to the creation of healthy, connected and affordable communities”[47], wrote the London School of Economics in its response to the New Draft London Plan. Christian Hilber comments wryly that:

“One may be quite sympathetic to this notion of not building on the green belt because what you probably have in mind is beautiful landscapes and areas where very rare birds are nesting, and that Londoners will go to the green belt for recreation purposes. This is not true at all. […] It’s too far away, it’s too difficult to get there. It’s not attractive, to a good extent it’s dense agricultural land. From an environmental point of view, actually, low-density residential is probably environmentally better than that dense agriculture. And yes, we need to produce potatoes, but maybe not just outside of the city that has the worst housing affordability problems in many decades”.

Christine Whitehead, Professor at the London School of Economics, confirms that the decision not to leverage some of the Green Belt’s land despite high levels of tension in London’s residential stock is a “political statement by the Mayor. From an economist’s point of view, it is total nonsense. The Housing Minister and others are MPs for Green Belt constituencies – that doesn’t help”. Luke Murphy also confirms the political reasons behind the refusal to use Green Belt land: “there are various things in policy, including housing, which I think are regarded as too difficult to touch, and Green Belt is one of them […] If we could ensure that, particularly through the Green Belt, the benefit of that value and the uplift in value goes towards infrastructure, roads and schools and could guarantee more affordable housing, I think you could start seeing a different debate. But you’d need mechanisms to ensure that you get that kind of viable, sustainable, development that people will support, as opposed to just expensive three- or four-bedroom houses”.

Many have spoken out to propose potential reforms to the current Green Belt system with a view to releasing land to ease the strain on residential stock. Some recommend a complete abolition of the Green Belt, “a step which could solve the housing crisis without the loss of any amenity or historical value” and would “enable towns once again to grow organically and spontaneously and people to live nearer to their jobs”[48]. Another solution, championed by Professor Paul Cheshire, would be to extract land from London’s Green Belt located within a ten-minute walk of a tube station, which would release enough land to build one million new homes. The question is, however, whether the housing crisis will become so critical that it will overcome political resistance to use this land.

Housing construction: a highly concentrated sector

In the UK, local authorities have a long-standing key role in affordable housing. “Since the Second World War, we have only ever met housing need with a significant contribution from the public sector. Between 1948 and 1978, local authorities built an average of 90,000 council homes a year, but by the 1990s it was next to nothing”, writes Luke Murphy. “Research by the Institute for Public Policy Research last year showed that 92 per cent of local authorities were failing to build the number of affordable homes their areas needed”[49]. A clear indicator of this trend, the boroughs, which once were major producers of affordable housing in London, have gradually distanced themselves from this role, in particular under the council housing sale mechanism introduced by the ‘Right to Buy’ policy of the Thatcher government which “resulted in 1.3 million households purchasing their council homes in the 1980s and 2.5 million households from 1980 to today” reminds Hélène Steinmetz[50]. 113,090 housing units moved from local authority to private ownership in the 1980s. It is proving difficult for the boroughs to replace this housing as the council housing stock is now significantly reduced. In a more general sense, the role of local authorities in building affordable housing has receded considerably: once those primarily responsible for residential construction in London, they have only completed a negligible quantity of homes in the last twenty years. “Now we have a much less diverse house building sector where the local authorities’ provision is radically declined. You’ve got housing associations which are making some provision and this has certainly increased, but far less than it was in the past”, notes Luke Murphy.

This significant decline in house building by local authorities has made the private sector responsible for producing most new homes in London. At the same time, this sector has become highly concentrated, even on a national level: “The nine house builders in the FTSE 100 and FTSE 250 hold 615,152 housing plots in their land bank, according to financial disclosures. This is four times the total number of homes built in Britain in the past year”[51]. In London, the production of affordable housing is currently in the hands of a limited number of major private developers. This concentration is partly due to the complex nature of managing relations with the boroughs, each of which has its own administration and plan. As a result, the sector is broken down into small companies active in a single borough and “very large developers, able to throw the necessary resources, albeit at some cost, in dealing with multiple planning authorities”[52].

These private developers focus on large-scale housing projects, the value of which is provided by housing sold at relatively high prices on the open market at a pace that some observers deem too slow. Nationally and in London, this sluggishness is often considered to be a compounding factor of the housing shortage: “Developers tend to release completed dwellings on to the market in each development site at a speed which maximises their margins — a speed which may be much slower than had been assumed by planning authorities in compiling their forecasts and targets […] It has not been in the power or in the interests of house building firms to lower land prices or to secure a steady supply of cheap land and thus create conditions for mass-production of the dwellings which are needed: to do for housing what IKEA has done for furniture”[53]. It is not in the interests of developers to deliver their housing in extremely short timeframes, as the Housing Finance Institute notes:

“Developers need a pipeline of land because the process of buying all the required land, obtaining planning permission and building out a site can take years. […] House building is labour intensive, and with large sites there needs to be a steady flow of work for the various skills that are required rather than, for example, trying to install bathrooms or kitchens in 4,000 units that are exactly the same time. And, sensibly, developers do not aim to complete a large site all at the same time because local markets cannot absorb a huge increase in supply at prices that make a development worthwhile”[54].

A group of researchers from the London School of Economics have shown that “even on sites that will eventually have thousands of homes, developers usually sell only a few hundred a year”[55]. It should also be noted that local housing markets “cannot absorb a high volume of new supply without reducing prices so much as to threaten the viability of the scheme. […] This is therefore a risky business requiring significant capital and can be done only by large companies”[56].

This sluggishness in turn feeds into suspected land speculation, further bolstered by the fact that 210,000 cases of planning permission granted in London have not yet resulted in any building. Developers are often accused of acquiring and then holding land with development prospects “until it can most profitably be used, the timing depending upon the spatial evolution of prices and their fluctuations”[57]. Yet this problem must be put into perspective, as it is not so much the developers who conduct such practices, but rather investors: the Molior report published in December 2012 notes that “45% of homes for which permission had been gained would not be built because the companies that had secured them were not actually in the building business”. Owner-occupiers, historic land owners, government, investment funds and developers ”who do not build”, were listed[58]. At the same time, as The Guardian reports, the Molior report states that “if work on every site for which planning permission had been obtained at that time began immediately ‘somewhere between 50,000 and 70,000’ homes would be completed for each of the ensuing three years”[59].

Based on the twofold observation of a concentration in the housing production sector and the slowness of building completion, deemed to be factors which explain the broadly insufficient supply of affordable housing, the GLA has set an objective to diversify the construction sector: “From my point of view, the key thing to keep us building is to shift away from this expensive market housing-driven system. And to have a lot more different actors, councils, associations, institutional investors, as well as the big builders”, explains James Murray, Deputy Mayor for Housing in London.

The GLA intends to meet this objective of diversity by tackling several points. First of all, it aspires to become a housing builder in its own right or at the least to significantly increase its own current production. James Murray explains as follows:

“One of the most promising avenues would be to give the public sector a greater role in directly building housing. We want to encourage the small builders, we want to encourage investors in rent and so on, but we have to have the public sector alongside that to complement it and to really increase the level of affordable housing. The private sector model is not going to double output so they recognize we need something complementary to that, which is the public sector”.

Another avenue that the GLA intends to pursue to diversify the sector is that of developing the role of SMEs in the production of affordable housing. “Around half of all housing construction used to be undertaken by SMEs but many were killed by the financial crisis”[60]. Obstacles which are currently hindering these SMEs’ access to the market include the cost of obtaining planning permission, insufficient access to financing through credit and above all the lack of small sites, land with a surface area lower than or equal to 0.25 hectares and with capacity for up to 25 housing units. “We want to increase the number of particularly small sites delivering housing because that creates more opportunities for small builders”, explains James Murray. The Draft New London Plan expects that 38% of the annual housing target of 65,000 homes will be delivered on small sites in the next decade. This development is set to be concentrated in the outskirts of London, with consultancy company Lichfields estimating that the boroughs of Outer London could deliver 68% of the total units on small sites.

Council tax: the GLA’s Achilles heel?

The GLA stands apart from other local authorities in charge of cities of comparable size by its narrow degree of latitude in terms of tax. “70 per cent of London’s revenue comes from central government, compared to 26 per cent in New York, 16.3 per cent in Paris, and 5.6 per cent in Tokyo”[64], notes the Centre for London. “The UK has a very centralized tax system where most of the taxes are collected at a national level”, explains Christian Hilber. “The main taxes, income tax, the value added tax, are collected at the national level. There is only a tiny tax, the council tax, that is at the local level”. Council tax, “a local tax levied on domestic residential properties”[65], is the focus of one of the fiercest debates on affordable housing in London today. Council tax descends from the poll tax, introduced in 1990, “a flat rate charge to be paid by every adult at a locally set rate”[66]. The introduction of the poll tax proved to be a “political disaster”, as the IPPR puts it[67]. The tax was believed to have shifted the tax burden from rich to poor households. A widespread campaign of non-payment as well as protests and riots ensued, with some now citing the poll tax as the reason behind Margaret Thatcher’s resignation as Prime Minister[68]. In 1994, the poll tax was replaced by the current council tax, presented as “more politically pragmatic” and which, according to the IPPR, is a “hybrid of a property-based tax, a consumption tax and a charge for local services”[69]. Properties are assigned into eight tax bands (A to H) based on their value. “The ratios between the council tax band rates are set by central government but the overall level – via a Band D rate to which all other bands are pegged – is set locally”, i.e. in London, by each borough, which results in significant spatial inequalities which contribute to the tax’s current unpopularity[71].

Income from the council tax is collected and received by local authorities (by London’s boroughs) and is one of the main sources of funding for local authorities. In London, boroughs are becoming increasingly dependent on income from this tax, in particular due to a decline in government aid triggered by a national austerity policy.

Yet “as it stands, council tax isn’t capable of meeting the funding gap – London boroughs need to make cuts of more than £540 million in 2018, yet a 1 per cent increase in council tax would raise little more than £30 million”[72]. In London, the IPPR notes that “there are 3.6 million domestic residences in London which are liable for council tax, comprising 15 per cent of England’s total housing stock of residential homes. The majority of these homes (57 per cent) are located in London’s outer boroughs. […] London has a higher proportion of homes in the upper council tax bands as a consequence of its high house prices – 15 per cent in bands F to G compared to just 8 per cent in the rest of England”[73]. The most common band in London is Band C (27% of housing stock); across England, Band A is the most common, accounting for 28% of homes, compared to only 4% in the capital.

Why is the council tax currently being called into question and why is it raised so often in debates on the shortage of affordable housing in London? Firstly, this tax is based on property values set in 1991, meaning that the current amount of the tax is totally uncorrelated to the real value of the taxed property. “Absurdly, when a new build property is constructed today, there is a need to calculate what the value of the property would have been over a quarter of a century ago for council tax purposes”, notes IPPR[74], which states “the failure of successive governments to conduct a revaluation on the property prices upon which council tax bands are based”[75].

Another criticism of this tax is its regressive nature, which is said to penalise low-income households. IPPR estimates that the highest value property in Band H will attract a maximum of three times the tax on the lowest value homes. This is despite the fact that a Band H property is worth at least eight times that of a Band A property[76]. “This means that as a proportion of property value, lower valued properties pay a larger proportion than higher value properties”[77]. Council tax disadvantages households living in low-value homes, while these households are often low-income households, the very ones targeted as a priority by the affordable housing initiatives conducted by the GLA and boroughs. In addition, the continued use of 1991 property values in the calculation of council tax amounts “renders the tax base fundamentally inelastic because it doesn’t increase until more homes are built or properties are revalued”[78].

The council tax is also considered to be a cause of the growing spatial inequalities, as each local authority[79] sets the amount for Band D. Council tax rates therefore vary from one London borough to another, and “bear very little relation to house prices”, notes IPPR[80]. The Band D rate is therefore higher in Outer London than in Central London. This reflects a combination of factors including “local priorities and needs, the political priorities of borough councils, and the distribution of properties across council tax bands”[81].

Ultimately, the council tax curbs the production of affordable housing in London. In its current form, it places a disproportionate burden on the lowest-income households, while its inefficiency deprives the GLA of precious resources that it could reinvest in building affordable homes. According to Christian Hilber, it discourages local authorities from investing in new housing:

“If a local authority in the UK permits development, it will receive a little bit of additional revenue through the local council tax. There are new people moving in, who will pay local council taxes, but that’s a very small tax. At the same time, they must provide the infrastructure – water, electricity, roads, et cetera – and these development projects lead to more congestion on the roads, more pressure on local schools, more pressure on local services, social services, etc. Local politicians have no incentives whatsoever to permit local development. So they say, ‘We have a housing crisis, we need to build more housing, but not in our borough’. That’s driven by the current tax system”.

All these factors have resulted in an increasing number of people calling for a council tax reform. Some are already considering what such a reform could entail (see p.33). Yet the political fiasco of the poll tax, which left a lasting impression, has created a high level of political reluctancy to tackle such a reform, despite the highly negative view the British have of the council tax[82]. However, a reassessment of the value of taxed properties, for example, could be a means to capture systematically any increases in land value resulting from public investment, as the GLA explains:

“If the council tax system were reformed to be more in line with current property prices – and frequent revaluations were in place – then any increase in property prices derived from a new transport scheme or improvements to the public realm (for example) should feed through into increased tax receipts automatically”[83].

Some experts are even advocating a full abolition of the council tax, to be replaced by a new tax with a view to encouraging a more efficient use of land, which has become scarce in London. The Mirrlees review conducted in 2010 by the Institute of Fiscal Studies notes that “taxing land ownership is equivalent to taxing an economic rent—to do so does not discourage any desirable activity. Land is not a produced input; its supply is fixed and cannot be affected by the introduction of a tax”. Yet there are several barriers blocking the introduction of such a system: “Introducing Land Rent Value Taxes is politically risky, since it requires major reform, creating winners and losers across the whole population of a defined territory. It is also practically difficult, since land in urban areas is rarely sold without existing property on it, and therefore cannot be readily valued through market prices”, explains the Centre for London[91].

The London case study is interesting as it provides an atypical example of a local authority, the Greater London Authority, which is currently ill-equipped in the battle it must fight against rising land and housing prices and the growing shortage of homes accessible to low- or medium-income households. With its limited latitude in terms of land consolidation and the inefficacy of one of the only available local taxes, the GLA is obliged to deal with many obstacles which curb its ability to produce affordable housing itself, or at the least to encourage its production by other parties. Another major obstacle stands in its way, this time political: the GLA’s decision not to use the land reserves in London’s Green Belt, which, if put to better use, could possibly increase the stock of affordable housing in one of the most expensive capitals in Europe.

1 KHAN, Sadiq. We’re starting to fix London’s housing crisis. But the government has to help. In: The Guardian. [on-line]. Published on 27 October 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/oct/27/were-starting-to-fix-londons-housing-crisis-but-the-government-has-to-help. (Viewed on 12 September 2018)

2 CHU, Ben. UK houses now cost almost eight times average earnings, says ONS. In: The Independent. [on-line]. Published on 26 April 2018. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/uk-house-prices-average-earning-ratio-latest-unaffordable-housing-crisis-a8323086.html. (Viewed on 12 September 2018)

3 EDWARDS, Michael. Prospects for land, rent and housing in UK cities. [on-line]. Working paper. London: Government Office for Science, Foresight, 2015, 55 p. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/440527/15-28-land-rent-housing-uk-cities.pdf. (Viewed on 11 June 2018)

4 Ibid.

5 The ratio of income is the ratio between total expenses related to the primary home and the household’s income (source: INSEE – French national institute for statistics and economic research). For tenants, these expenses include the payment of rent and charges in addition to housing tax. For homeowners, they include the repayment of a mortgage taken out to purchase the housing and the payment of condominium fees and land and housing taxes.

6 HILBER, Christian. UK Housing and Planning Policies: the evidence from economic research. [on-line]. London: Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics, 2015, 16 p. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/61745/1/ea033.pdf. (Viewed on 13 June 2018)

7 BARRETT, S./DILKE, T. Strength in Numbers: Funding and Building More Affordable Housing in London. [on-line]. Policy report. London: Centre for London, 2017, 71 p. Available at: https://www.centreforlondon.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/CFLJ5181_strength_in_numbers_policy_report_0217_WEB.pdf. (Viewed on 12 June 2018)

8 EDWARDS, Michael. Prospects for land, rent and housing in UK cities. [on-line]. Working paper. London: Government Office for Science, Foresight, 2015, 55 p. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/440527/15-28-land-rent-housing-uk-cities.pdf. (Viewed on 11 June 2018)

9 Ibid.

10 BARRETT, S./DILKE, T. Strength in Numbers: Funding and Building More Affordable Housing in London. [on-line]. Policy report. London: Centre for London, 2017, 71 p. Available at: https://www.centreforlondon.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/CFLJ5181_strength_in_numbers_policy_report_0217_WEB.pdf. (Viewed on 12 June 2018)

11 SCANLON, K./WHITEHEAD, C./BLANC, F. A Sustainable Increase in London’s Housing Supply. [on-line]. Research report. London: London School of Economics, 2018, 24 p. Available at: http://lselondonhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/REPORT_LSE_KEI_digital.pdf. (Viewed on 13 June 2018)

12 BARRETT, S./DILKE, T. Strength in Numbers: Funding and Building More Affordable Housing in London. [on-line]. Policy report. London: Centre for London, 2017, 71 p. Available at: https://www.centreforlondon.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/CFLJ5181_strength_in_numbers_policy_report_0217_WEB.pdf. (Viewed on 12 June 2018)

13 SCANLON, K./WHITEHEAD, C./BLANC, F. A Sustainable Increase in London’s Housing Supply. [on-line]. Research report. London: London School of Economics, 2018, 24 p. Available at: http://lselondonhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/REPORT_LSE_KEI_digital.pdf. (Viewed on 13 June 2018)

14 EDWARDS, Michael. Prospects for land, rent and housing in UK cities. [on-line]. Working paper. London: Government Office for Science, Foresight, 2015, 55 p. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/440527/15-28-land-rent-housing-uk-cities.pdf. (Viewed on 11 June 2018).

15 BARRETT, S./DILKE, T. Strength in Numbers: Funding and Building More Affordable Housing in London. [on-line]. Policy report. London: Centre for London, 2017, 71 p. Available at: https://www.centreforlondon.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/CFLJ5181_strength_in_numbers_policy_report_0217_WEB.pdf. (Viewed on 12 June 2018)

16 Ibid.

17 A draft version of the “London Plan”, a strategic plan for the development of Greater London, signed by the Mayor of London and published by the Greater London Authority. The first London Plan was published on 10 February 2004 and was revised in 2004, 2008 and 2011. The current London Plan, published in 2016, was amended in January 2017 and will remain in force until 2036.

18 BOLEAT, Marc. The Housing Problem in London – a broken planning system. [on-line]. Research paper. London: The Housing & Finance Institute, 2017, 29 p. Available at: http://thehfi.com/downloads/housingprobleminlondon.pdf. (Viewed on 14 June 2018)

19 Disused land.

20 PUGH, T./SEAGER, J. Wasted Space to Living Place – Using surplus public land for housing in London. London: London First, 2015, 16 p.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 In the United Kingdom, the county council is a non-metropolitan council in charge of education, transportation and social services. In London, these councils are given the honorary title of boroughs.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Home Truths – 12 steps to solving London’s housing crisis. London: London first, 2014, 38 p.

27 The Mayor of London defines the Greater London development strategy through the “London Plan”. The Mayor is always consulted for planning permission applications of strategic importance (i.e., in practice, applications for projects involving at least 150 housing units).

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 CHESHIRE, Paul. Are they Green *Belts* by Accident? In: LSE Spatial Economics Research Centre. [on-line]. Published on 22 May 2015. http://spatial-economics.blogspot.com/2015/05/are-they-green-belts-by-accident.html. (Viewed on 5 June 2018)

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 PAPWORTH, Tom. The Green Noose: An analysis of green belts and proposals for reform. [on-line]. Research report. London: The Adam Smith Institute, 2015, 64 p. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56eddde762cd9413e151ac92/t/56f71c957c65e4881ff6e395/1459035287095/The-Green-Noose1.pdf. (Viewed on 12 June 2018)

37 Ibid.

38 CHESHIRE, Paul. Are they Green *Belts* by Accident? In: LSE Spatial Economics Research Centre. [on-line]. Published on 22 May 2015. http://spatial-economics.blogspot.com/2015/05/are-they-green-belts-by-accident.html. (Viewed on 05/06/2018)

39 CHESHIRE, P./SEAGER, J./STRINGER, B. The Green Belt: A place for Londoners? [on-line]. London: London First, 2015. Available at: http://londonfirst.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Green-Belt-Report-February-2015.pdf. (Viewed on 6 June 2018)

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Ibid.

46 PAPWORTH, Tom. The Green Noose: An analysis of green belts and proposals for reform. [on-line]. Research report. London: The Adam Smith Institute, 2015, 64 p. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56eddde762cd9413e151ac92/t/56f71c957c65e4881ff6e395/1459035287095/The-Green-Noose1.pdf. (Viewed on 12 June 2018)

47 BLANC, Fanny. Draft London Plan consultation LSE London Response. In: LSE London Housing. [on-line]. Published on 24 mars 2018. http://lselondonhousing.org/2018/03/draft-london-plan-consultation-lse-london-response/. (Viewed on 14 June 2018)

48 PAPWORTH, Tom. The Green Noose: An analysis of green belts and proposals for reform. [on-line]. Research report. London: The Adam Smith Institute, 2015, 64 p. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56eddde762cd9413e151ac92/t/56f71c957c65e4881ff6e395/1459035287095/The-Green-Noose1.pdf. (Viewed on 12 June 2018)

49 MURPHY, Luke. To create housing for the many not the few, we should reform Britain’s land market. In: CityMetric. [on-line]. Published on 23 April 2018. https://www.citymetric.com/politics/create-housing-many-not-few-we-should-reform-britain-s-land-market-3855. (Viewed on 14 June 2018)

50 STEINMETZ, Hélène. Les politiques du logement en Europe : comparaisons. Cahiers français, 2015, n°338, p. 8-14.

51 BOLEAT, Marc. The Housing Problem in London – a broken planning system. [on-line]. Research paper. London: The Housing & Finance Institute, 2017, 29 p. Available at: http://thehfi.com/downloads/housingprobleminlondon.pdf. (Viewed on 14 June 2018)

52 Ibid.

53 EDWARDS, Michael. Prospects for land, rent and housing in UK cities. [on-line]. Working paper. London: Government Office for Science, Foresight, 2015, 55 p. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/440527/15-28-land-rent-housing-uk-cities.pdf. (Viewed on 11 June 2018)

54 BOLEAT, Marc. The Housing Problem in London – a broken planning system. [on-line]. Research paper. London: The Housing & Finance Institute, 2017, 29 p. Available at: http://thehfi.com/downloads/housingprobleminlondon.pdf. (Viewed on 14 June 2018)

55 HOLMAN, N./FERNANDEZ-ARRIGOITIA, M./SCANLON, K./WHITEHEAD, C. Housing in London: Addressing the Supply Crisis. [on-line]. London: LSE Knowledge

Transfer: Higher Education Innovation Fund, 2015, 20 p. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64158/1/Fernandez_Arrigoitia_Housing_in_London.pdf. (Viewed on 7 June 2018)

56 BOLEAT, Marc. The Housing Problem in London – a broken planning system. [on-line]. Research paper. London: The Housing & Finance Institute, 2017, 29 p. Available at: http://thehfi.com/downloads/housingprobleminlondon.pdf. (Viewed on 14 June 2018)

57 EDWARDS, Michael. Prospects for land, rent and housing in UK cities. [on-line]. Working paper. London: Government Office for Science, Foresight, 2015, 55 p. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/440527/15-28-land-rent-housing-uk-cities.pdf. (Viewed on 11 June 2018)

58 HILL, Dave. London Housing Crisis: Tackling Landbanking. In: The Guardian. [on-line]. Published on 2 March 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/davehillblog/2014/mar/02/london-housing-crisis-landbanking. (Viewed on 11 June 2018)

59 Ibid.

60 HOLMAN, N./FERNANDEZ-ARRIGOITIA, M./SCANLON, K./WHITEHEAD, C. Housing in London: Addressing the Supply Crisis. [on-line]. London: LSE Knowledge Transfer: Higher Education Innovation Fund, 2015, 20 p. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64158/1/Fernandez_Arrigoitia_Housing_in_London.pdf. (Viewed on 7 June 2018)

61 BARRETT, S./DILKE, T. Strength in Numbers: Funding and Building More Affordable Housing in London. [on-line]. Research paper. London: Centre for London, 2017, 71 p. Available at: https://www.centreforlondon.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/CFLJ5181_strength_in_numbers_policy_report_0217_WEB.pdf. (Viewed on 12 June 2018)

62 Ibid.

63 Ibid.

64 BOSETTI, N./BROWN, R. Fiscal Devolution and Reform to Strengthen London. In: Centre for London. [on-line]. Published on 13 July 2017. https://www.centreforlondon.org/reader/open-city-london-after-brexit/fiscal-devolution-and-reform-to-strengthen-london/#council-tax-reform. (Viewed on 6 June 2018)

65 MURPHY, L./SNELLING, C./ STIRLING, A. A Poor Tax – Council Tax in London: Time for Reform. [on-line]. London: Institute for Public Policy Research, 2018, 60 p. Available at: https://www.ippr.org/files/2018-03/a-poor-tax-council-tax-in-london.pdf. (Viewed on 13 June 2018)

66 Ibid.

67 Ibid.

68 Ibid.

69 Ibid.

70 Ibid.

71 Ibid.

72 Ibid.

73 Ibid.

74 Ibid.

75 Ibid.

76 Estimate based on 1991 prices.

77 Ibid.

78 The Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) gives the example of a Band A home, with an estimated value of £40,000 in 1991 and which would have paid a council tax rate of £275 in 1993, while a Band H home, with a value of £320,001 would have paid £824. The same Band A house, now valued at £209,600, would pay an average council tax rate of £689 in 2015/2016 (i.e. 0.33% of its value), compared to £2,037 for the Band H property currently valued at £1,676,800, which represents a council tax rate of only 0.12% of the property’s value.

79 Ibid.

80 Ibid.

81 In London, each borough.

82 Ibid.

83 The Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) gives the example of a Band H property (the highest band), located in Westminster, valued at £10 million, which would pay £1,345 in council tax, i.e. less than a Band C property located in Harrow with a value of £240,000, which would have paid £1,359 in 2015/2016.

84 Ibid.

85 Ibid.

86 WINGHAM, Mark. Council Tax in London – A publication for the London Finance Commission. [on-line]. Working paper. London: GLA Economics, 2017, 100 p. Available at: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/council-tax-in-london-wp-80.pdf. (Viewed on 14 June 2018)

87 Ibid.

88 Ibid.

89 MURPHY, L./SNELLING, C./ STIRLING, A. A Poor Tax – Council Tax in London: Time for Reform. [on-line]. London: Institute for Public Policy Research, 2018, 60 p. Available at: https://www.ippr.org/files/2018-03/a-poor-tax-council-tax-in-london.pdf. (Viewed on 13 June 2018)

90 WINGHAM, Mark. Council Tax in London – A publication for the London Finance Commission. [on-line]. Working paper. London: GLA Economics, 2017, 100 p. Available at: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/council-tax-in-london-wp-80.pdf. (Viewed on 14 June 2018)

91 Ibid.

92 Ibid.

93 BOSETTI, N./BROWN, R. Fiscal Devolution and Reform to Strengthen London. In: Centre for London. [on-line]. Published on 13 July 2017. https://www.centreforlondon.org/reader/open-city-london-after-brexit/fiscal-devolution-and-reform-to-strengthen-london/#council-tax-reform. (Viewed on 6 June 2018)

94 Ibid.

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Helsinki : Planning innovation and urban resilience

Forget 5th Avenue

Long live urban density!

The ideal culprit

Behind the words: density

Behind the words: Affordable housing

German metropolises and the affordable housing crisis

Berlin Focus

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.