Cities in the race for quality of life: between local area marketing and a new approach for urban policy

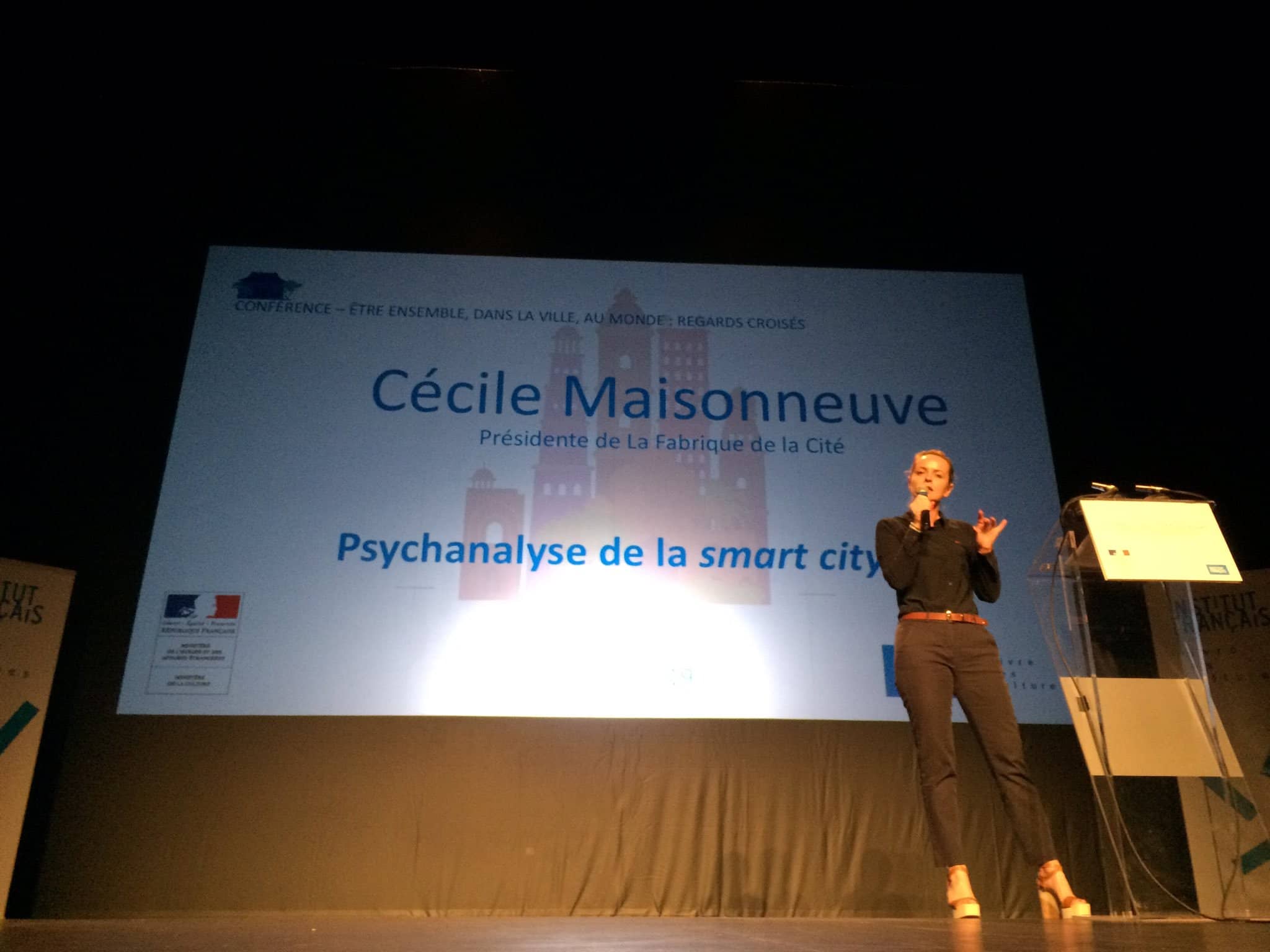

Each year, the Mercer rankings assess quality of life in cities across the globe. In 2019, Vienna topped the list for the tenth year running. Along the lines of this ranking, there are an increasing number of labels and cities are competing to obtain them: they have become genuine local area marketing tools. What are the challenges related to assessing quality of life in cities? Quality of life can be defined and assessed according to which criteria? Which realities are concealed behind these many labels? La Fabrique de la Cité looked at these questions during its international seminar held in Vienna in July 2018.

What is quality of life?

The term quality of life emerged in the 1960s, when the consequences of massive urban development and industrialisation were starting to be felt in Western nations. At the time, it referred to the conditions necessary for an individual’s personal development.

At the end of the 1990s, Amartya Sen claimed in his work on the economics of well-being that quality of life is “the individual freedom to use one’s capabilities to act on something, to produce acts and to achieve goals that are meaningful to them”. A city that offers optimum quality of life would therefore be a city in which individuals can thrive in a healthy environment. This definition of quality of life naturally makes the notion more complex than if it is considered merely in terms of amenities and facilities to be made available to inhabitants.

How can quality of life be measured?

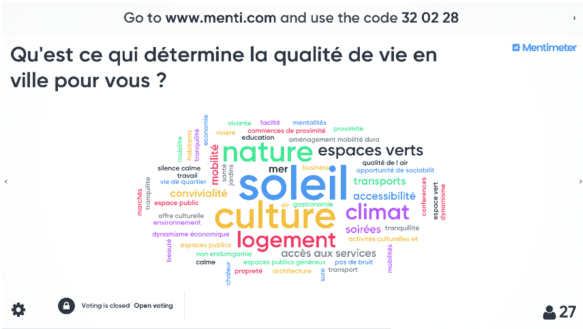

Can quality of life be measured? The existence of reputed rankings and assessments, such as those produced by Mercer or the OECD, point to this conclusion – as their differences indicate that each ranking uses different indicators and weightings. “Measurement institutes do not agree on which measurement tool to adopt”, commented Aziza Akhmouch, Head of the Cities, Urban Policies, and Sustainable Development Division of the OECD. Behind the apparent simplicity of their rankings and their extreme clarity, which are often deftly reworked in local area marketing initiatives (“the top 10 best cities to live in”, “the 20 medium-sized cities which are reinventing quality of life”, etc.), the measurement of quality of life is a major challenge: it has direct repercussions not only on the competitiveness of the cities concerned but also on the definition of public policies. The measurement of quality of life has become an important tool in the steering and management of cities – a tool which is not quite like others due to its reliance on a certain definition, or interpretation, of what quality of life is.

There is a history of quantitative criteria. Which city has the best GDP, the best HDI, the most dynamic growth or the longest life expectancy? Which infrastructure is available in its area? The Mercer ranking, for example, is based on these criteria, explained Slagin Parakatil, principal at Mercer. Such criteria have the advantage of being objective and can be measured on different scales, both spatial and temporal, and therefore comparisons can be made between 231 cities across the world. These criteria, which measure international standards, are particularly relevant in view of Mercer’s desired objective: to give major companies a tool to calculate the hardship allowance to be allocated to their internationally-mobile employees.

However, even in this very specific regard, Mercer has decided to add to the quantitative data conventionally used for this type of assessment, with qualitative data that can reflect lifestyle and certain local value systems: “Mercer also takes into account subjective data, on the basis of the concerns of the inhabitants in different cities, in the weighting of its measurements”, specified Slagin Parakatil. “The use of a vehicle and its environmental impact is a concern which does not have the same importance in India as in Europe for example”. Such adjustments tend to show that quality of life cannot be considered and measured solely in terms of international standards and without taking the local situation into account: individuals’ requirements in terms of quality of life – even for highly international workers – vary depending on their city of residence and adapt to this city.

This is the reason why the OECD has also reviewed its measurement instruments. “There are limits to the approach based on per capita GDP and the argument of strong growth”, confirmed Aziza Akhmouch. There are two types of limits: firstly, these indicators ignore the citizen’s point of view– an argument shared with Mercer; secondly, they are not indicative of the environmental and social impact of the policies conducted, or of the actual endorsement of the infrastructure made available: providing the number of roads or hospitals indicates a potential but does not state who can access them or the quality of the service provided by such infrastructure. To understand whether all inhabitants can access a better quality of life and under which conditions, the OECD has developed a Better Life Index. This is innovative in the way it highlights possible social disparities and introduces criteria requiring subjective points of view (the perceived quality of social relations, the work-life balance, etc.) yet it also allows each person to rank the different indicators in accordance with their own understanding of quality of life in order to create a personalised ranking of cities.

This approach is therefore a departure from a certain universalist vision of quality of life. Quality of life seems to be the result of a combination of three separate and complementary concepts[1]:

- “Objective” quality of life, which measures internationally defined standards.

- “Normative” quality of life, which is reflected in local area marketing, focused on a few strong ideas. This societal image, which is extremely powerful in this era of mass media, is a benchmark from which we can assess our own lives and our own understanding of a good life. Yet this does not necessarily reflect what each person is individually aspiring to.

- “Subjective” quality of life, which reflects strictly individual preferences, which are more or less influenced by the first two categories and also primarily by each person’s personal experience, value system and private recollections of places.

This approach to quality of life requires a review of measurement and statistical skills. Aziza Akhmouch claimed that “there is intense debate within the OECD as regards the indicators which measure well-being. Today, a multifaceted approach is essential and it must be developed so that decision-makers can conduct appropriate policies”. The potential for innovation remains very high here: which new indicators should be developed? How can statistics be adapted to measure subjective and qualitative aspects? The question is raised more keenly as we now understand that quality of life does not depend solely on quantifiable elements: how can the atmosphere of trust in a place be measured, the tolerance expressed or the ability of people to forge community ties in a space? These criteria contribute fully to inhabitants’ individual and collective development as defined by Amartya Sen. How can cities be created in which individuals have the freedom for their personal development and can conduct actions which are meaningful to them?

The discussions on indicators reveal significant tension between an individual understanding and a collective understanding of quality of life. The challenge for cities and public authorities is to overcome this tension in a balanced manner: can the total of individual optima constitute a collective optimum?

The ups and downs of rankings

Quality of life rankings are increasingly used as tools to guide public policy. As Slagin Parakatil explained, they can act as a stimulus for public authorities. The Mercer ranking sends them a mirror image of their city as an external assessment of how it functions. It highlights the strengths and weaknesses of the different cities in view of the trends governing international quality of life standards. The strength of the ranking compiled by Mercer lies in its consistency from one year to the next: it can be used to make a reliable comparison over time on the basis of the same indicators, to observe positive developments or impairments to quality of life and to assess the impact of the policies conducted. The Mercer ranking has become a genuine benchmark for both public and private stakeholders, to the extent that the company has developed a consulting service aimed at local authorities, in addition to its corporate services. The impact of the rankings therefore exceeds their primary objectives and they have become excellent instruments for cities’ economic development, as they are used primarily as a powerful local area marketing lever to attract talent. Thomas Madreiter, head of urban development at Vienna city council, confirmed this: “cities are now competing on a global scale to attract the best talent, the best companies and the best researchers…. The Mercer ranking is therefore very important as it enables Vienna to enjoy great visibility on an international level and to be attractive”. Cities also view the rankings as a tool to encourage a positive feeling of belonging and pride among inhabitants that cements the community. However, all rankings are based on a comparison – and all comparisons, if they are correctly used, require us to be aware of their limits: what are we comparing and to what extent is the comparison valid?

The first limit to comparisons lies in the difficulty of establishing common indicators for all cities worldwide, in particular due to the very different levels of data availability and collection in cities: “how can sufficient similar data be collected in all countries, given that the territorial scales, available amenities and practices and habits in the city differ?”, questioned Aziza Akhmouch. Qualitative polling institutes do not operate in all countries for example and do not all enjoy the same quality. While we manage to obtain precise information for OECD countries, data collection is more complex in African nations for example, stated Slagin Parakatil.

The second limit concerns the scope studied: what does “quality of life in Paris” mean? Is the boundary the municipality of Paris? Greater Paris? The Paris region? Very few rankings specify clearly the scope selected and even fewer justify their methodological choices. However, for most indicators, the choice of scope plays an important role, which could mean a city going up or down a few places in the ranking, or could even bias the assessments. Aziza Akhmouch stressed the importance of interactions between local areas: “[they] go well beyond the regulatory administrative boundaries and borders are porous. It is thought that the population of a city is inflated by around 75% of its inner-city population in practice – commuters, individuals seeking public services which are unavailable or even inexistent in their local area”. If this parameter is ignored, the measurements can be distorted for some indicators. This is why “we must change the way we look at cities, and adopt a broader dimension than the conventional administrative boundaries. The OECD has decided to base its assessment criteria on cities’ functional areas”, explained Aziza Akhmouch. These functional areas take into account local areas which are closely connected in the way they operate.

Vienna, champion of quality of life

Vienna has topped the Mercer rankings for ten years running. However, in the collective consciousness, Vienna is rarely among the cities perceived to have the highest quality of life. Vienna, ville Janus[2], is full of paradoxes, and yet, how can its continued presence at the top of rankings be explained? What is the basis of quality of life in Vienna? What can be learned from the Viennese approach?

Vienna has been conducting a proactive quality of life policy for many years, which has earned it the top place in the ranking. It does not, however, view this position as an achievement but as an incentive to continue the work undertaken. This is based on an original positioning: the idea is not to define what quality of life is in Vienna but to develop an agile and flexible methodology to meet inhabitants’ expectations and requirements as much as possible and thereby offer them a better quality of life, the definition of which changes. “In Vienna, we place the emphasis on the social aspect of life in the city. Quality of life involves making connections between inhabitants and this is a real challenge for the city council and urban planners. For us, it is also very important to understand the needs of the Viennese and to be able to provide them with an environment in line with these needs”, confirmed Thomas Madreiter. To do so, tools aimed at fostering citizen dialogue are required. The city council has, for example, developed the DISKUTO platform, which encourages the Viennese to get involved in a certain number of issues concerning life in the city.

The originality of Vienna’s approach is also due to a strong interconnection between the different timeframes for action:

- the present, of course, by understanding inhabitants’ needs and drafting appropriate responses,

- and also the past, through an acute awareness of the heritage of past policies (going back very far, such as affordable housing policies, in addition to more contemporary policies), seen not as a burden to be carried but as an untapped potential. This is made possible in particular by an in-depth public policy assessment approach rolled out to estimate the extent to which the objectives set by a public policy were reached, or not reached, and to analyse the actual impact of actions conducted at grassroots level,

- and lastly the future, through the identification of opportunities available to the city and the consideration of threats to what has been gained in terms of quality of life. The city council has set itself the following strategic goal: how can the level of quality of life which makes Vienna famous and attractive be maintained in the future while protecting its resources as much as possible?

This interconnection between the past, present and future enables the city to tackle long-term challenges and to ensure that the gains from the various policies conducted are protected, while retaining a certain flexibility in its actions.

While Vienna does not become blinkered by the definition of quality of life, it nevertheless advocates a certain approach. This involves building up a “Stadt für’s Leben” (city for life), the aim of which is to promote social inclusion, maintain a heterogenous society and reduce social and economic inequalities. To reach this objective, it has decided to place its quality of life policy at the core of its “smart city” strategy, and in doing so disrupts the codes which are usually related to this strategy.

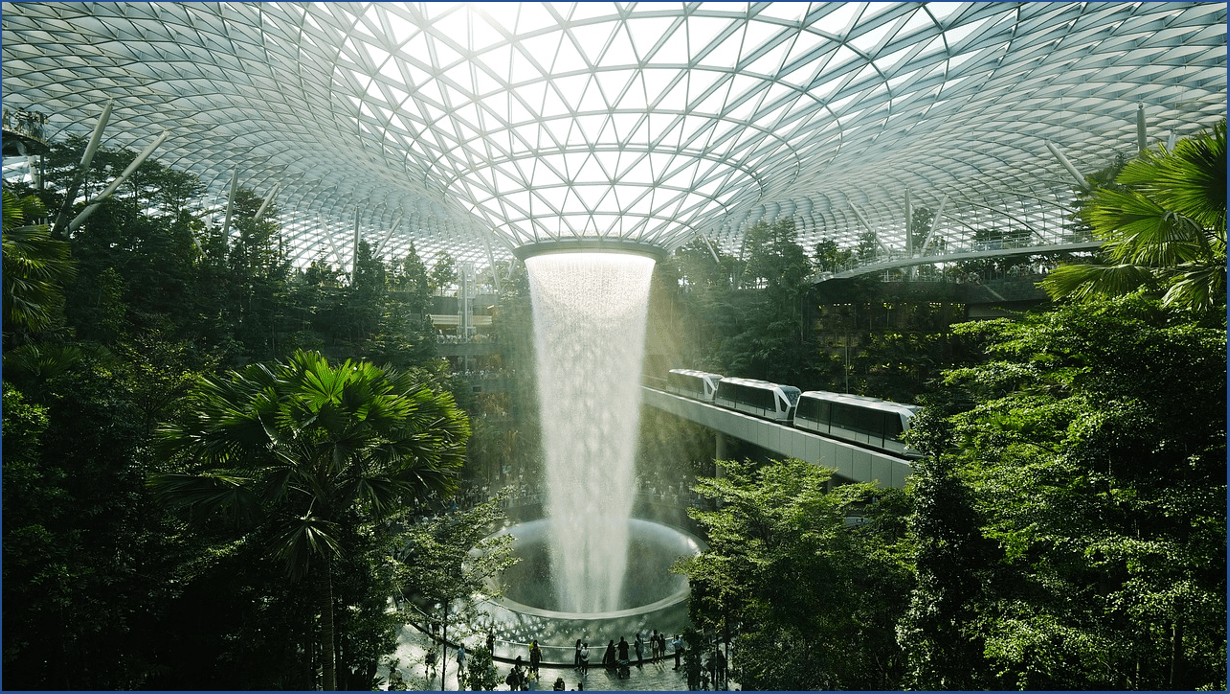

The promise most commonly made in “smart city” strategies is to make the city more efficient and better managed through new technologies, which are used to collect and process a quantity of data which was hitherto unachievable. Data must afford an understanding of habits and actual users and therefore be leveraged to develop services which are more likely to meet individuals’ needs – and not those of socio-economic profiles which erase the specific features of the persons that make them up. The promise of the “smart city” is therefore clearly linked to the ambition of improving quality of life. Furthermore, strategies have changed significantly since the responses provided by the first “smart cities” such as Songdo and Masdar: staking everything on technology without including the human aspect, they failed in the objective of improving quality of life. The “smart city” strategies are now more subtle. They have understood that quality of life cannot be defined solely by an optimisation of daily life: Singapore has created a “Centre for liveable cities” to consider the interconnections between technologies and social sciences.

How is Vienna’s “smart city” strategy innovative? By distancing itself from new technologies themselves, that it views simply as some of the tools at its disposal and on no account as its cornerstone. This strategy is based on the following three pillars: (1) to preserve resources, (2) to develop and leverage innovations and new technologies, and (3) to achieve a high level of socially‑balanced quality of life. “What makes inhabitants feel good in their city?”, asked Thomas Madreiter before claiming that “innovations in a smart city, which is what we call a city focused on its long-term future, must go further than technological innovations. Technology is necessary but not sufficient”. This position has two significant consequences: the first is a certain shift of focus away from the very concept of the “smart city”, for which the label and therefore local area marketing dimension is acknowledged and nevertheless accepted as a major part of Vienna’s international urban policy. Thomas Madreiter joked that “the term smart city is very widely used today. Words such as ‘intelligent’ and ‘smart’ are now used unduly: my grandfather smoked ‘smart’ cigarettes and today we build ‘smart’ cities…”. The second consequence is the importance attached to social innovations in Vienna’s “smart city” strategy, such as the creation of the public transportation pass costing one Euro per day or the social mobility assistance rolled out by the city council. These innovations, which are not based on the use of new technologies, have brought about a swift drop in the number of vehicles in the Austrian capital.

The Viennese approach to the “smart city” is therefore interesting in that it offers a new interpretation of the meaning of “smart”: a city is “smart” if it successfully puts people and the satisfaction of their needs at the centre of its policies, regardless of how (with or without new technologies), including all those who are not and will not be service users. In doing so, Vienna overcomes the tension often observed at the centre of “smart cities” between, on one hand their ambition to be user-centric, and on the other the reality of the actions conducted, which do not result in an improvement to everyone’s quality of life. Vienna, with its approach which aims to achieve a social balance, successfully combines “smart city” and quality of life.

[1] City Life: Rankings (Livability) Versus Perceptions (Satisfaction), Adam Okulicz-Kozaryn, “Social Indicators Research”, Vol. 110, No. 2 (2013), pp. 433-451, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24718714

[2] La Fabrique de la Cité. Portrait de ville : Vienne. Juin 2018. En ligne. URL : https://www.lafabriquedelacite.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/FABRIQUE_VIENNE_20180627_WEB_FR.pdf

Find this publication in the project:

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Toronto: How far can the city go?

The political and technological challenges of future mobilities

Viktor Mayer-Schönberger: what role does big data play in cities?

Thomas Madreiter: Vienna and the smart city

Vienna

Breathless Metropolises

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.