“Dig, baby, dig”

Traffic is driving me nuts. Am going to build a tunnel boring machine and just start digging…

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) 17 décembre 2016

And then he dug. In late December 2016, Elon Musk, tired of Los Angeles’s traffic jams, decided to enter the tunnel business, in addition to his numerous other futuristic projects. Following this, the Boring Company was created. Located near the Space X hangars, the first tunnel boring served as a feasibility demonstrator in agreement with the City of Los Angeles. Yet this experience alone failed to satisfy the Californian entrepreneur’s ambitions; Elon Musk had much greater projects for the city. Consequently, in December 2017, he presented his vision for the future of car mobility in Los Angeles, based upon one question: why had we used the third dimension to accommodate people yet continue to build a two-dimensional mobility infrastructure network?

Thus, while cities have resorted to exploring heights (and urban sprawl) to accommodate a growing urban population in the last centuries, the solution to urban congestion may lie underground. By multiplying infrastructure layers, the network could absorb the mobility demand… and enable users to free themselves from the rules of land traffic. Such a network would combine the perks of public transport (priority lane) and cars (reduced cost). Thus, a futuristic project… If it had not already been imagined in the 1920s.

Futurama offered a vision of the city of the future sponsored by General Motors in 1939 at the New York World Fair. ARAMIS is a network of small cars running as trains. More recently, an elevated bus riding on top of traffic was imagined. Network or modal projects promising to solve the complexity of urban issues have always existed. However, this complexity may not be solved solely by the customization of an itinerary, congestion avoidance, or the burying of roads. If these projects have not been pursued, it is precisely because of their tendency to circumvent complexity rather than try to figure out and act on what prevents the seamless mobility of the majority of urban residents. Where to start from then? A first approach to this complexity involves understanding that mobility isn’t all about speed. It is also about capacity. What effects on mobility flows can we expect from a system that allows only a small amount of people to ride faster than 200km/h? Would this still be mass transit? Whom would this be directed to?

Although public transport and land traffic solutions might be uncomfortable and “boring”, they provide efficient mobility solutions to urban populations. Such projects will certainly offer a faster and more comfortable solution than an overcrowded train or a congested avenue, but it would not be able to meet the complete demand for urban mobility. Let us think of the model’s archetypical infrastructure denounced by Elon Musk: the Paris RER A moves 1.2 million travelers everyday, that is to say more than Lyon’s (France’s second biggest city) whole public transport scheme. Despite all the externalities it generates, the Parisian ring road remains the main mobility solution for 1.3 million daily users.

Before even succeeding in transporting the city’s residents, wouldn’t this project transform Los Angeles’s underground into a genuine golf course?

Subscribe now and never miss another Urban Snapshot.

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Lisbon beyond the Tagus

Helsinki : Planning innovation and urban resilience

Sending out an SOS

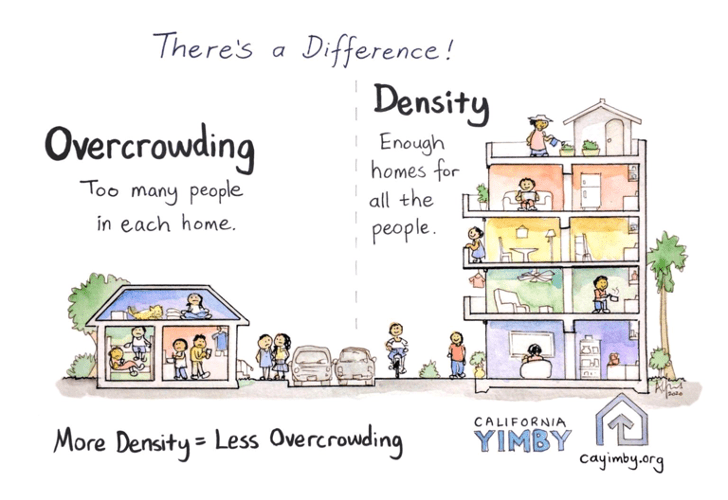

Behind the words: density

Behind the words: telecommuting

Behind the words: urban congestion

Toronto: How far can the city go?

The political and technological challenges of future mobilities

Inventing the future of urban highways

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.