Embracing complexity: how Singapore became Singapore

“In Esmeralda, city of water, a network of canals and a network of streets span and intersect each other. […] Since the shortest distance between two points in Esmeralda is not a straight line but a zigzag that ramifies in tortuous optional routes, the ways that open to each passerby are never two, but many, and they increase further for those who alternate a stretch by boat with one on dry land.”

Complexity isn’t what is complicated. Complexity is non-linearity, unpredictability. In our societies, complexity is an unavoidable parameter. It is systemic and, hence, is inherent to cities, which involve exchanges and flows of people, knowledge, money, and goods[1]. Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities[2] relates the unpredictable life of Esmeralda, city of water, where “a network of canals and a network of streets span and intersect each other. […] Since the shortest distance between two points in Esmeralda is not a straight line but a zigzag that ramifies in tortuous optional routes, the ways that open to each passerby are never two, but many, and they increase further for those who alternate a stretch by boat with one on dry land.” This narrative presents complexity in all of its living nature, in all of its sophistication, which challenges the rules of simplicity by ignoring the itinerary that, at first sight, looks to be the shortest.

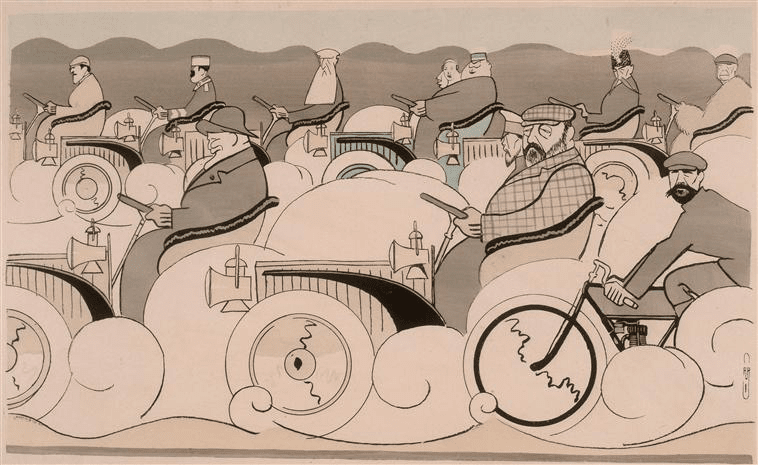

The journey to modern Singapore began in 1819, when a small fishing village was turned into a warehouse port by the British, offering a new maritime route to the British East India Company through the strait of Malacca. A confrontation with complexity soon occurred, when, to fulfil British trade aspirations, the city appealed to massive immigration from Southeast Asia, China, and India. The waterfront and the hinterland, which was once a luxurious rainforest transformed into vast plantations, became a place of encounter for men from various origins, speaking diverse languages and worshipping different gods. The Enlightenment had left a trace in Europe, and, in 1822, the Jackson Plan, drawn by the British, distinguished quarters based on their activities and workers’ ethnicity; the Plan, though it left an enduring legacy, failed to stand the test of time or practices. Nowadays, power and cultural institutions remain concentrated within the European city, characterized by its neoclassical and neo-Palladian architecture, although it is not rare to glimpse, at the corner of a Chinatown street, in between two shophouses, a temple adorned with shimmering Hindu deities. The invention of the automobile, tinned food, and new rubber processing methods, followed by the inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1869, firmly enshrined Singapore as a key port for trade in Southeast Asia.

The Japanese occupation (1942-1945) damaged the legitimacy of British government over the island. Anticolonial political parties emerged and helped the city gain progressive autonomy. In the midst of the Cold War, left-wing factions advocating the use of Chinese languages against the supremacy of English were seen as a threat to Western liberalism and were severely repressed. In 1954, the People’s Action Party, an English-speaking anticolonial political party, was born, led by the man who would become Singapore’s founding father after the nation’s independence in 1965: Lee Kuan Yew.

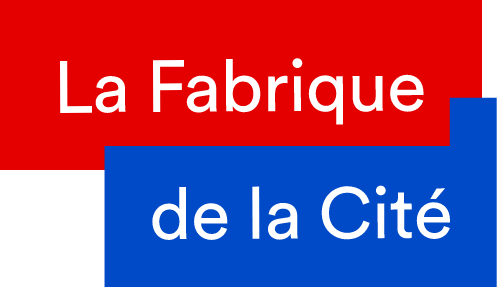

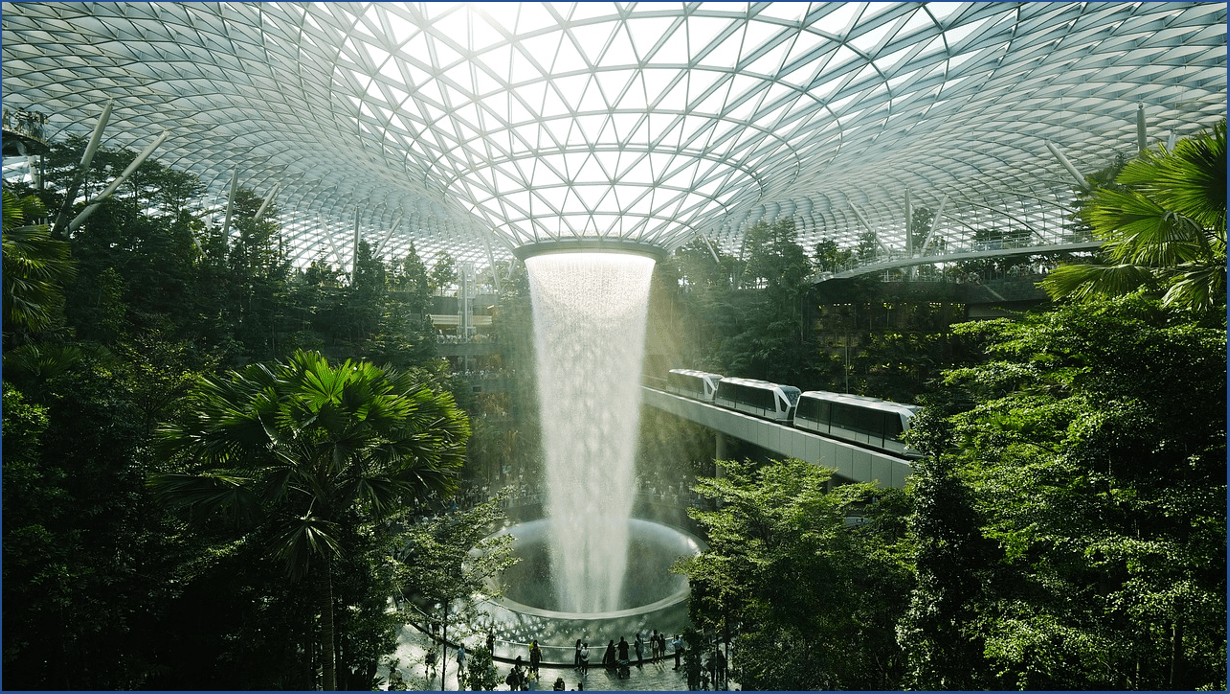

Post-independence years elapsed to the hectic pace of cranes and cement mixers. Accommodating a growing population requires building high and fast, as does fulfilling development ambitions. In 1987, the World Bank declared Singapore a high-income country: the city-state had become a world class financial centre and nicknamed “the Switzerland of Asia.” The 1997 Asian financial crisis curbed Singapore’s growth only to better complete its transition to a knowledge economy. Singapore’s resounding success was reflected in the expansion of its business district, with the opening of the Marina Bay Sands in 2010, and by the designation of the Botanic Gardens as a UNESCO world heritage site in 2015. Today, the overlapping of a digital layer and the physical layer hastens our experience of the city. This acceleration has been exacerbated by algorithms, substantially reducing the processing time and adaptative capacity of governments and citizens[3]. The smart city, as efficient as it promises to be, heralds a new era of complexity.

The English title of the ”Trading Cities” chapter in The Invisible Cities echoes the mercantile foundation of Singapore’s success. It nonetheless fails to translate the richness of what cities have to offer; Italo Calvino writes more broadly of exchanges, ”le città e gli scambi” in its original version. Modern Singapore is in essence a blend of cultures, and its language, or perhaps its languages, are in the image of its history. These languages reveal a subtle complexity ; in life as in town, they offer a clever mix of Malay, Chinese, and Indian idioms, Peranakan Creole and English, which is manifest in the city’s toponymy: Fort Canning Hill borders Dhoby Ghaut (in Hindi, “the launderer on the river steps”), while Jalan Bukit Merah (in Malay, “the red hill street”) delimits the Tiong Bahru neighbourhood, a combination of “thiong“, (“cemetery”, in Chinese Hokkien) and “bahru” (“new”, in Malay).

Is Singapore only this straight, logical and efficient city, as its glass and steel Central Business District, where men and women linked to the world via their smartphone come and go in a hurry, would have us believe? Its richness may not be encapsulated in the mere term “globalized city”. Singapore offers multiple facets, all cosmopolitan, to whoever follows its maze, through traditional quarters or through the new “towns” which blossomed in the 1970s, to discover local lives as they thrive a few kilometers away from downtown.

[1] Ho, P. (2017). The black elephant challenge for governments. Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/the-black-elephant-challenge-for-governments

[2] Calvino, I. (2006). Invisible cities. Orlando, FL [etc.]: Harcourt.

[3] Ho, P. (2018). Conference: Complexities of Time – Opening address. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-cSpNNK2SEs

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Behind the words: urban congestion

Toronto: How far can the city go?

The political and technological challenges of future mobilities

Nature in the city

Viktor Mayer-Schönberger: what role does big data play in cities?

Thomas Madreiter: Vienna and the smart city

“Once Upon a Time”…

Boston Focus

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.