Governing the city through/with digital data : The Big Disruption ? Conversation with Antoine Courmont

In the era of digital technology, data is becoming a key resource for urban governance and a major political and legal challenge for public institutions, which are destabilized by the rise of new players – specifically from the platform economy. The increasing production of data is the source of numerous challenges for public and private actors alike, especially as regards the accumulation and use of data and the creation of value that can be derived from it. La Fabrique de la Cité spoke with Antoine Courmont, researcher in political science, scientific director of the Cities and tech Chair at Sciences Po, and co-author of Gouverner la ville numérique (Governing the digital city), a book published in August 2019.

La Fabrique de la Cité : In your book, Gouverner la ville numérique, you marked 2008 as the pivotal year of the digital transition. Why exactly did you choose that year?

Antoine Courmont: It was primarily an assumption based on several concurrent developments. Firstly, 2008 was the year that the iPhone 3G became widely used, which marked the advent of the digital era, when IT became pervasive and penetrated all our environments. The iPhone has an amazing capacity to capture data and is also a device which provides services to people on the move. 2008 also saw the emergence of new urban stakeholders with very distinctive characteristics, namely digital platforms such as Airbnb (2008) and Uber (2009). Lastly, the global economic crisis of 2008 was an opportunity to rethink capital accumulation on the basis of data. A good example is the smarter city concept launched by IBM at the end of the 2000s, which introduced the digitisation and optimisation of how urban environments function through data. 2008 was selected as the turning point for all these reasons.

Our assumption is based on the postulate that there are new forms of data-related accumulation that are connected to digital technology. I am unable to say whether or not this is a new capitalistic system. However, we have observed that there are new stakeholders (digital platforms) whose business is predominantly or exclusively based on accumulating or leveraging data. Many conventional urban companies have also embarked upon the digitisation of their networks and data-led optimisation. They are now offering different services to what they traditionally offer. This is the case for Veolia, Suez, and Engie, which no longer restrict their business to the management of urban networks and now do business in the integration of data-related systems, dashboards and a wide range of digitisation services.

« We have observed that there are new stakeholders (digital platforms) whose business is predominantly or exclusively based on accumulating or leveraging data. »

LFDLC : Looking back at the history of science and technology, it can be noted that each technological revolution resulted in a period of uncertainty. Is digital technology radically disruptive?

We are at the beginning of a time of major uncertainty. The situation is changing very quickly, and we do not know what the positions are going to be. For example, when IBM entered the urban arena in the 2000s with its smarter city idea, the traditional market players were unsettled: the leading urban industrial players feared that IBM would manage information systems and cities worried about privatisation. Ten years on, after several failed partnerships (Veolia-IBM for example) due to a lack of skills and expertise, IBM has completely withdrawn from the smart city market. We can now observe that traditional players and public authorities are capable of renewal and some have strengthened their position through digital technology. In addition, we have noted that, in practice, digital technology has significantly heightened pre-existing trends. For example, Airbnb has worsened the problem of a housing market that is already severely overloaded. The same can be said of Uber: the job insecurity of Uber drivers is part of a general trend of an insecure labour market.

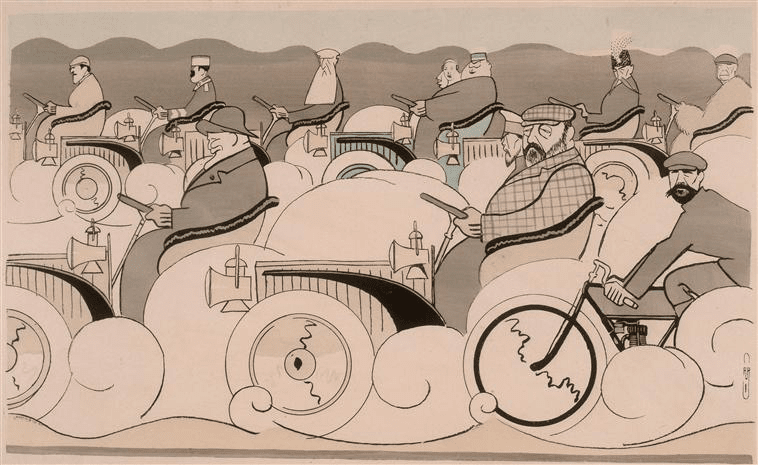

The truth is that any economic player wishing to develop its market looks for an opening. This is not simply the case of stakeholders in the digital sector. If Waze thrives off an imbalance, it does meet a need that results from a problematic management of infrastructure, urban sprawl, and a lack of alternatives to individual cars. The people in charge of regulating traffic have told me that, in some situations, Waze can be more responsive and effective than their own services, even if there is a disruptive shift of traffic to other districts. Along the same lines, Uber’s success is partly due to unsatisfactory services provided by taxis and public transportation. Chauffeured vehicle services are less spatially selective, as drivers cannot select their passengers according to their destination.

LFDLC : Ultimately, what is digital data? Is there a difference with simple data?

I don’t really make a distinction between digital and pre-digital data, as, for me, data has always existed. However, the move from IT to digital is a real change in that information technology, which is no longer restricted to computers and information systems, has become more significant and has penetrated all of our environments (personal, urban, work, etc.) This change, which comes on top of a number of technological developments, has in particular resulted in an increase in available data and more specifically in a new kind of data that can be placed in the category of big data.

LFDLC : The term big data is often used. How would you define it?

I don’t have an exact definition because I am primarily interested in how we could define this new quantification system, i.e., counting the number of social facts, which is different to statistics. Many people focus on the adjective “big” to emphasise the importance of mass. We do produce much more data than before. This increase raises a number of technical challenges, which are being quite well met by technological developments. However, this outlook is less interesting for a social science researcher.

« We do produce much more data than before. This increase raises a number of technical challenges, which are being quite well met by technological developments. »

I am more interested in the fact that we have many more records of behaviours and practices that allow us to identify them more effectively and in doing so to be able to govern them. We talk about digital traces, which can be on- and off-line. Furthermore, data circulates much more than before, particularly within companies and administrations but also between companies and administrations. This favours the use of data through circulation, and not solely through accumulation, which is what platforms do. I am interested in the public-private relationship in the urban sector, between public authorities, “conventional” private players, major digital platforms (Uber, Waze, Airbnb, etc.), for which the business model is exclusively based on data and their ability to accumulate, leverage and process data.

LFDLC : What exactly is a digital trace? How is it different to data?

In practice, data is a general term that aggregates a lot of information. A digital trace is a type of data that concerns more specifically the passive recording of our activities, such as geolocation for example, which enables a company like Waze to calculate traffic speed and suggest routes on the basis of this information. The production of digital traces which can be used by public or private players to create algorithms is possible as IT is everywhere (in particular through smartphones).

Not only has digital technology enabled private players to accumulate data more easily, it has also enabled citizens, especially those organised in associations, to accumulate as much data (e.g. Open Street Map), which would have been inconceivable prior to the widespread availability of GPS sensors and the low cost of data storage and production. It is interesting that now, on the basis of the data they possess, private companies and citizens can offer a counter-representation and a counter-rhetoric which contrasts with official state rhetoric. This may be a significant factor of emancipation, particularly in non-Western societies in which data production is not as strong. In Brazil, for example, for a long time the favelas of Rio did not appear on the map, as the city had never agreed to map them, as this would amount to acknowledging their existence. It was Google, in partnership with a local association, which decided to map the favelas. Their inhabitants were very proud of this. Data can therefore be a key factor in representing and legitimising populations. In many major cities in the south, where there was previously no data on all informal forms of transportation, there are now maps that enable these networks to exist.

LFDLC : Is this what you call in your book “transforming the city with data”?

When I talk about using data to transform the city, I am referring specifically to data production. Today, data production in the urban sector costs much less than it used to; this has resulted in new digital stakeholders emerging in this field. The restructuring of power relationships in relation to data is interesting. Now, major administrations are not the only ones who are able to produce data: these new stakeholders are testing the “state’s semantic power”, to quote Boltanski – the ability of public institutions to define a reality and to coordinate a number of individuals in relation to it.

Public bodies have therefore been disrupted, sometimes to a great extent in some areas. It is nevertheless important to stress that there are factors that recompose their power: this is not the death of public institutions, they regulate even private players and platforms in particular, even if this is done retrospectively. Uber and Airbnb, which are both emblematic urban platforms, have undergone stricter regulation in recent years and are for example prohibited in certain cities. This regulation will most likely contribute to a change in behaviour for these players; even if Airbnb is still in a confrontational mindset, Uber is increasingly leaning towards a partner-based approach. We must also remember that private players need a stable legal framework to develop their business and that, in this respect, they require regulation in a form most favourable to their activity. The digital urban markets are for the most part jointly developed between public and private stakeholders. The differences in balance are in the power relationship between these players.

« It is nevertheless important to stress that there are factors that recompose their power: this is not the death of public institutions, they regulate even private players and platforms in particular, even if this is done retrospectively. »

While there is the additional matter of expertise in public administrations, I have been struck in recent years by the fact that we tend to focus on the lack of expertise and undermining of public players and not enough on the fact that digital technology has kicked off an era of major uncertainty, for both public and private players in equal measure. When there is any form of technological innovation, there is necessarily an increase in society’s skills. This must happen but does take time. It is therefore unsurprising that there is a lack of expertise.

LFDLC : In your book, it seems like you are suggesting two new forms of governmentality: one through digital traces and the other through algorithms. Can you expand on this?

They are simply new types of instruments. The core of digital technology is data and algorithms. In practice, they are both inseparable: one feeds into the other. This is why they must be analysed together. The way in which methods of governing individual behaviours through digital traces and algorithms have been stepped up is quite clear. In the last fifteen years, there has been an increase in the individualisation of responses to a number of social issues, excluding digital technology. Today, digital technology is used to enrich these algorithms which steer our individual behaviours in a direction deemed more virtuous. This involves, for example, multi-modal applications which offer us all the options of getting from A to B. While this is nothing new, digital technology does heighten this steering of behaviour for the modal shift. We are currently able to gain real knowledge of individual practices and even to attempt to predict future practices which can be leveraged to steer individual behaviours. This is what Waze does when it guides drivers to one route or another.

LFDLC : Today, new data types are emerging, such as open data. What are they and what are the governance methods involved?

Supported by the ideology of information liberalism, the economic and activist movements have, in a way, forced public players to make their data available, for transparency reasons and also for economic development purposes. Open data in particular has contributed to the change in governance methods: while public players were the only ones to be able to use data, today other players can enjoy access to it. Depending on the way in which data is made available, its reuse will be geared towards some purposes which are more or less in line with public policy and a certain sense of general interest. This is why I don’t believe there is a single form of open data, but rather several forms. Take, for example, the Lyon metropolis (Grand Lyon), which I have studied. The water, transportation, waste management, and energy policies do not have the same types of data, the same interests, or the same configurations of players and challenges. These different policies will have different ways of disclosing data.

From the 2010s, open data became widespread in France and in Europe, with the idea that it would necessarily lead to economic development. Many players adopted open data, convinced that there would be major economic benefits. Yet, ten years on from the first initiatives, there haven’t been many benefits and very few applications manage to stay on this market in the long term. Open data raises many issues: all data produced is intended for a specific use, which makes reuse for an alternative purpose quite complex. Open data has, however, been used to optimise project management (on building sites, for example) as it improves the coordination between the various stakeholders of public policy that could now use the same data. In addition, open data is used to a considerable degree within administrations themselves. I am currently conducting a study for the Grand Lyon concerning municipalities’ open data. All the town councils I have met have told me that open data has enabled them to produce quality data and to make it accessible to all municipal services, which is very useful for internal coordination and to modernise the administration. Yet, paradoxically, this is more complicated for major cities than it is for very small municipalities. The former must review the architecture of their information systems in relation to data and its circulation, while the latter usually start from scratch.

LFDLC : Could open data be a new foundation for local democracy? Could it be associated with a form of empowerment of local societies?

This really depends on the area. Some cities or municipalities stress their aim of transparency through open data (information, budget, etc.), which would foster citizen participation. That said, the data made available is generally not particularly accessible to citizens, who therefore require the assistance of an expert to open a CSV (comma-separated values) file and understand it. I am quite sceptical about the idea of empowerment through open data. When local authorities refine the data, they modify it and sometimes remove information so that it can be reused. This means that the people who will have access to data do not necessarily have all of the details. The political importance behind this can therefore be quite significant.

LFDLC : If the digital transition of data is not used to empower populations, should it be feared?

Digital technology is not all bad. One thing it does is to provide us with new and useful services that optimise the way the urban environment functions. The book Gouverner la ville numérique strives to demonstrate that we are a long way from seeing a uniform trend. Using data is very complex. It depends on the stakeholder, the local area, the type of data, particularly as data is quite poorly structured.

However, it can definitely be said that digital technology disrupts some public players. Airbnb, for example, is greatly unsettling for the city of Paris and its housing policy. Going beyond public opinion, we are witnessing a swift change in the issue’s focus (a challenge for tourism, technology, or social matters, etc.) and therefore the way the policy is steered will depend on this focus, on which players are involved and the power balance within administrations. Thomas Aguilera, Francesca Artioli, and Claire Colomb analyse this aspect in one chapter of the book, in which they compare the way in which several major European cities regulate Airbnb. Stricter regulations will not result from the scale of the Airbnb phenomenon, but rather from the way in which the issue’s focus is defined (with which players and which configuration). This focus can also be defined through involvement within a single administration as there are many departments and each elected representative will have his or her own vision. At the city of Paris, for example, while Airbnb was initially considered as a tourism player with which public stakeholders had to work, it is now perceived by some, and in particular by Ian Brossat, deputy mayor in charge of housing, as a player to be confronted and regulated on the housing market. There are also tensions between levels of government with regard to these issues. The French state remains in favour of this rental platform for now, as it is aware that it is an asset for the country’s tourism policy, which is a significant economic policy.

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Behind the words: urban congestion

Toronto: How far can the city go?

The political and technological challenges of future mobilities

“Once Upon a Time”…

Boston Focus

Data for urban citizens

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.