Helsinki : Planning innovation and urban resilience

The wood industry is one of the country’s key sectors and the forest covers three quarters of Finland. Wood and paper production is the second largest export, and a long-standing tradition of wood construction is alive and well in Helsinki and beyond. However, the industry still faces many obstacles, despite Finland having created global giants in the sector. Developing wood production has now been technically constrained by the necessity to protect the resource and manage forests in a sustainable manner – without impeding the market’s growth. Some obstacles, both economic and political, particularly with the European Union, make it difficult to exchange best practices between countries, producers, and manufacturers. Our urban expedition has been an opportunity to understand how the Finnish State, alongside local authorities, and builders, are structuring a wood construction industry, from growing forests to building entire neighborhoods of state-of-the-art wooden buildings.

What lessons can be learned from the industrialisation of the wood construction sector? What makes a wooden building so innovative in Finland? From the forest exploitation to building with wood: how can we ensure the sustainable development of a very demanding and international sector?

The underground city is a more recent field of study than wood construction, but no less structured in Finland. In fact, Helsinki was one of the first cities in the world to have set up a plan for the use of its underground spaces. Often derived from previous military uses, underground facilities in Helsinki are not mere urban backstage areas designed to hide transport, waste, water and energy utilities. They also host places of worship, leisure, offices and even housing, most often reversible as bomb shelters. The city is emblematic of this shift in urban planning, where basements, once relegated to technical aspects, take on their full value at a time of densification, when space in the city has become scarce. This look at underground construction also reminded us that contemporary geopolitical struggles are still played out both above and below ground in Helsinki. Several questions arise when looking at how a city can accommodate and protect its underground spaces.

What contribution can the underground make to the realisation of an urban project in the context of a sustainable metropolis?

And how can an underground planning project nourish the city’s resilience? Finally, there is a strong question of governance and political management of the underground space. Can it be developed as a normal urban space, or does it need its specific rules and political organisation? How can we make sure both dimensions (over and under-ground) are linked?

Helsinki’s development reflects Finland’s history and construction

A short History of Helsinki’s development and construction

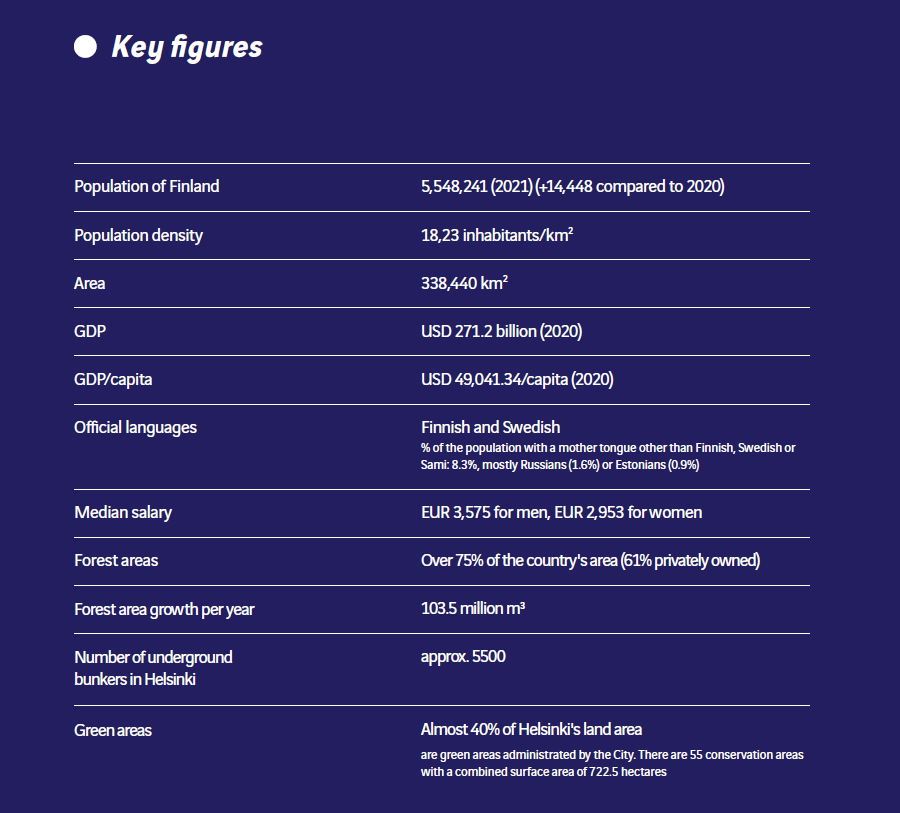

Most of Finland’s history is intertwined with Sweden and Russia: a heritage Helsinki’s architecture keeps a trace of. The country has been occupied by Sweden between the 14th and 19th centuries, before being conquered by Russia in 1808-1809, and thus being annexed by the Russian Empire by Emperor Alexander I, who gave it the status of an independent Grand Duchy.

During the Russian period, Finland experienced a period of prosperity punctuated by conflicts with Sweden. It was under Russian hegemony that the City of Helsinki, then called Helsingfors, became the capital of Finland, replacing Turku, located on the west coast of the Grand Duchy, which was considered too close to Sweden both geographically and culturally. It’s also under this time that the city underwent a considerable expansion: the city center was rebuilt under the plans of Carl Ludwig Engel, and infrastructures such as the University of Turku – which was to become the University of Helsinki – were moved to the new capital.

Carl Ludwig Engel was a Prussian architect: he was born on July 3rd, 1778 in Berlin and died on May 14th, 1840 in Helsinki. His most notable work is the rebuilding of the City of Helsinki. His work includes the Helsinki Cathedral, the Senate Square and all the buildings surrounding it, the City of Helsinki Town Hall and many other prominent buildings of the Helsinki city center. Later in his life, he was also responsible for the new city plan for the City of Turku, in Western Finland, after it was almost destroyed by a great fire in 1827.

It was during the many conflicts between Russia and Sweden that a strong Finnish national identity was built. In 1917, taking advantage of the Bolshevik revolution raging in Russia, Finland gained its independence along with other territories that would become the Baltic States. It was on this occasion that Helsingfors changed its name to Helsinki. In 1918, however, a sanguinary civil war broke out in the country, resulting in a victory of the German-backed “Whites” against the Soviet-backed “Reds”. During this period, Germany and the USSR fought over Helsinki as an area of influence. In 1939, at the height of the alliance between the two powers, Finland and its capital city was assigned to the Soviet sphere of influence until the collapse of the German-Soviet pact, and then fought on the side of Nazi Germany.

During the War, Helsinki was repeatedly targeted by massive bombing raids from the Soviet air force. Fortunately, only a hundred buildings were destroyed, and 150 inhabitants killed. Helsinki had 275,000 inhabitants at that time. The war period generated strong population displacements and Helsinki grew by more than 50,000 inhabitants and its territory increased fivefold.

Finland and the USSR then went at war during the difficult “Winter War” (1939-1940), but both countries kept political and commercial relations after the conflict. However, following the fall of the USSR, Finland experienced a period of massive recession in the early 1990s. This ended in the mid-1990s, especially when the mobile phone giant Nokia had its heyday. Finland joined the European Union in 1995 and was also one of the first countries to adopt the euro as its official currency.

Helsinki’s general economic and institutional context

The City of Helsinki is built on a peninsula surrounded by over 330 islands and had most of its development shaped by its relation to water (ports, docks, commercial exportations, tourism and fishing). In fact, of the total area of 715.55 km2, only 213 km2 is on land. This characteristic and Helsinki’s openness to the Gulf of Finland make the city one of Finland’s largest trading ports. It’s also, on another note, the second most northerly capital in the world after Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland.

The Helsinki municipality is organised around the City Council, the executive body of local politics. Its responsibilities include city planning, urban development, schools and public transport. The city government has a strong power in urban planning and future development scheduling. It consists of 85 members who are elected every four years during the municipal elections. The City Council then appoints the mayor: this position is currently held by Juhana Vartiainen since 2 August 2021, a member of the National Coalition Party, a centre-right conservative and liberal party.

The City of Helsinki is divided into 60 districts (kaupunginosa) which exist for city planning purposes, and 34 districts (peruspiiri) which exist to facilitate the co-ordination of public services within Helsinki. In addition to this, the metropolitan area of Greater Helsinki includes the four municipalities that make up the Capital Region (Helsinki, Espoo, Vantaa, and Kauniainen) as well as 10 other municipalities, each with between 5,000 and 50,000 inhabitants.

Helsinki’s demographics differ greatly from the rest of Finland. The city’s population has grown steadily since the 1800s, reaching 658,457 in 2021, with projections of growth to 730,098 by 2040 according to Statistics Finland. In total, the Greater Helsinki region had 1,488,236 inhabitants as of 31 August 2018, which is just over 25% of the total Finnish population in 2018.

The city’s population is approximately 80% Finnish and 20% foreign. The largest minorities are Russian, Somali and Estonian. Due to its past strong ties to Sweden, Finland, and by extension Helsinki, has a large Swedish- speaking minority of between 5 and 7% of the population. Finnish and Swedish share the position of official language of the country.

Helsinki is a showcase of Finland’s construction techniques

Incorporating wood in the city

The timber industry

The Finnish timber industry is one of the country’s key sectors. It really began in the 19th century when the forest was heavily exploited and helped produce buildings, paper or heating products. Later in the 20th century, with the two wars and the USSR – once a good client of Finnish wood – setting its sights on petrol, the production could not be maintained at high speed. And after the Cold War, Finland progressively managed its forest as a recreational capital to be protected and progressively invested in other wood innovation, produced at a lower scale.

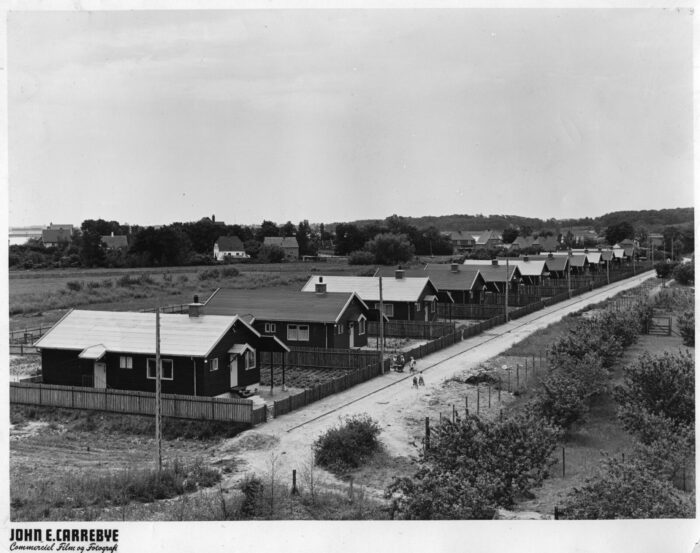

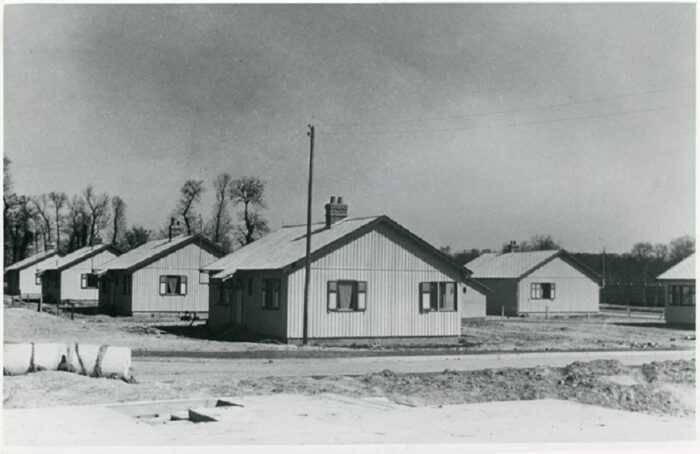

During the learning expedition, we met Laura Berger and Kristo Vesikansa, two architects and scholars of New Standards, which represented Finland at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021. Their pavilion presented the story of Puutalo Oy (Timber Houses Ltd.), an industrial enterprise established in 1940 in response to a national refugee crisis, when some 420,000 Finnish citizens were displaced by war. In this moment, architects and industrialists came together to create a new model of timber factory-built housing that not only modernized Finland’s construction industry but also became a worldwide export, expanding across all inhabited continents. From the very first order (10,000m2 of barracks built to house German troops in Norway) to today’s constructions (mainly individual houses), this story shows how Finland came with an innovative and adaptable way of building with wood. In fact, Puutalo houses can be found all over the world now, from Finland to Latin America. After the war, in 1946, Finland started exporting the house in exchange of raw materials, machinery and other essential goods. This success story is also an example of how close the cooperation should have been between European countries after the war.

Puutalo produced nearly 120 000 houses in more than 30 countries and definitely helped define the new standard of housing in the post-war reconstruction until 1955.

“As a global pioneer in the prefabrication of timber structures, the Puutalo corporation spread wood from Finnish forests across the globe in the form of schools, hospitals, dormitories and single-family homes, thousands of which remain in use.”

Supporting wood construction

In the 1990s, and to keep the wood industry at high speed while protecting the resource, Finland decided to invest in innovative products for the construction sector. Finland has long been famous for high-quality buildings made of wood, but at small scale or very localized. While Puutalo Oy is a very good example of innovative Finnish wood building, it remained localized and it is only today that prefabricated houses are back under development as well as modular construction for offices, train stations, warehouses, etc.

On that topic, Mikka Pesonen, head of sale of Stora Enso, a Finnish world leader in wood production, insists on the wide range of wood products specifically developed for construction. From digital tools to analyse a building’s components once it’s built to low-carbon wood material inserted into the construction process, Stora Enso is well engaged into the wood-based product market and keeps its role as a world leader. It’s the perfect example that the Finnish wood industry has a strong momentum and thrives through diversification of wood-derived products.

In fact, wood construction is also strongly promoted in key national planning documents, such as the Government Programme, the National Energy and Climate Strategy, the

National Forest Programme and, finally, the Finnish Bioeconomy Strategy. The most important is the National Wood Programme (2016-2022), which focuses on developing rules, regulation, and regional skills to promote wood construction. It also develops public- private practices between the public sector, construction industry professionals and the academic community. The target is to increase the market share of wooden constructions in public buildings to 31% by 2022 and to 45% by 2025. In fact, as shown by Petri Heino, Director of the National Wood Programme for the Ministry of Environment, wood building is particularly helpful in meeting Finland’s very ambitious goal: carbon neutrality by 2035, carbon negativity in the 2040s.

Sustainable forest management and the sustainability of the sector

Sustainable forest management is a major issue for the viability of the wood industry in the longer term: while wood is a particularly efficient material for capturing CO2, building with it may also lead to poor forest management, a progressive reduction in forest habitat for biodiversity or the loss of CO2 capture from these areas. Finally, the import of foreign wood for construction sites considerably increases the carbon impact of the operation.

There is therefore an important issue of training and regulation of the forestry system to manage the resource in a sustainable way.

To answer this issue, wood productors have been increasingly investing into new products: biofuels and combustible, wood for construction and bioplastics, with very high standards of resource protection and excellent rates of material use (with as little scrap wood as possible). The future and strength of the Finnish wood sector lie in this capacity to develop low-carbon solutions and an excellent ratio of used wood compared to cut down trees. In other terms, to limit the loss of the wood resource, each tree should be entirely used and integrated to the production process.

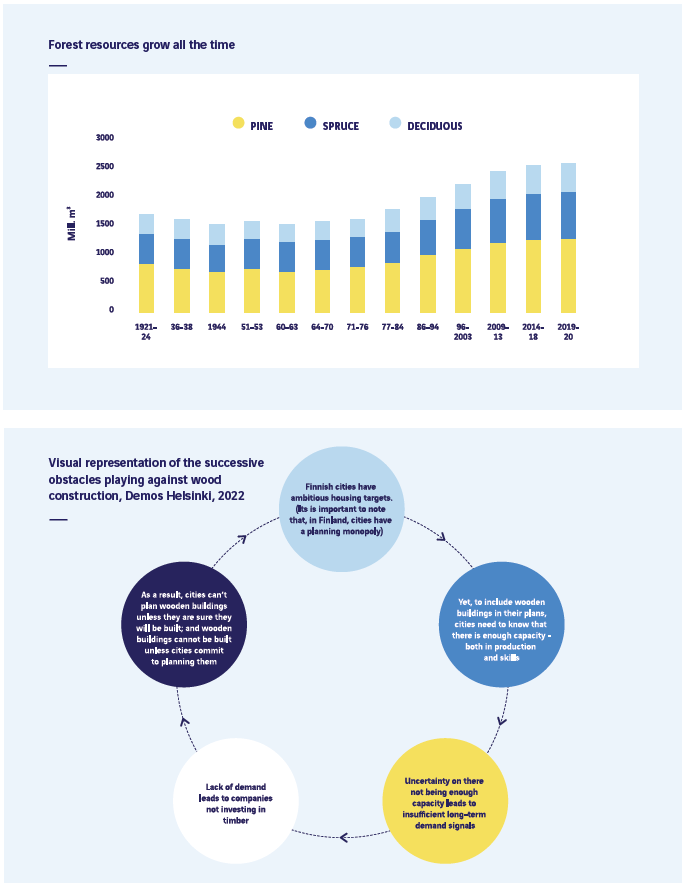

As shown by Petri Heino during the learning expedition, the Finnish forest is not in a bad situation either. In fact, the volume of the growing stock has increased in Finland since the 1960s, and the volume of trees is now almost two times higher than 100 years ago. Also, the annual increment of growing stock is bigger than total removals and natural mortality.

Protect the forest and use it at the same time, the Finnish National Wood Programme is based on many objectives, but all rooted in one principle: cooperation between industries, regions, countries. As a result, Petri Heino strongly defended the wood-based bioeconomy and bringing together public and private actors in the wood sector at national and regional level. The aim of the programme is also supporting investments in bio-based solutions and wood-based value chains. In fact, the biggest investment in the history of the Finnish forest industry (with a value of 1.2 billion euros) lies in the new bioproduct mill in Äänekoski, the first next generation bioproduct mill in the world, with low-carbon products and last-generation production methods.

However, according to a recent Finnish study, the wood industry is still dependent on energy intensive activities, and fossil fuels (peat, coal in boilers, oil and gas). The same study shows the sector could decrease its emissions with a strong reduction of fossil fuel use but, despite the abundance of initiatives and their innovative companies, widely used to highlight Finland’s commitment to cleantech and the bioeconomy, commercial results are still low. In summary, the use of wood in housing appears to be slowed down by a circle of operational obstacles, as summed up by the Finnish Think Tank Demos Helsinki:

In France, by comparison, the forest represents 31% of the national surface and grows at a rate of 85 000 hectares per year (10 000 football pitches). The French timber industry is dynamic but could benefit from a simplified system. As the President of the Union des Industriels et Constructeurs Bois, Frédéric Carteret told the urban expedition team how useful a simplification could be for the French timber industry. Indeed, he regretted that the sector was still very much divided between the forest management and the wood construction. Although this separation was not said to be conflictual, it surely doesn’t help the global industry to scale up the production and industrial process for wood to be incorporated into more construction projects. However, the new legislation adopted in France in January 2022, called “RE2020” will give a radical impulse to the wood construction. As shown by Armelle Langlois, head of sustainable performance at VINCI Construction, the regulation should pave the way for buildings that consume less energy (decarbonised energy) and that are adapted to hot weather. To reduce the impact of buildings on the climate, the regulations will then promote construction methods that emit little greenhouse gas, which means greater use of wood and biosourced materials, which have the advantage of storing carbon during the life of the building.

The French wood sector has therefore been given a major role with the RE2020. To accompany the entry into force of the regulation, the sector launched a “Plan Ambition Bois Construction 2030” in February 2021 to support the revival of sustainable buildings. In order to meet the government’s ambition and climate objectives, the sector’s professionals have set ten commitments, concerning the training of professionals, the development of employment, research and development, support for the regional economy, the development of the supply of French wood and the recycling of end-of-life wood.

Wood construction in Helsinki

As the capital of Finland, Helsinki is home to many wood buildings, and wood construction in the city epitomizes the different epochs of architecture and timber management.

The district of Puu-Käpylä is probably one of the most famous and historically preserved districts of Helsinki. Built in the 1920’s for poor working classes and workers of the construction sector, the district operates as a city on its own, with a very specific organisation of the wooden house. Houses were shared among several families with sometimes more than 3-4 people in the same bedroom. Each house has a courtyard which dominates the social life, directly inspired by the Garden City paradigm, coming from England and Germany in the 1920s. Threatened of demolition in the 1960s, the Protection Act voted in 1970 engaged its protection and general refurbishment.

However, since the 1990’s, demolishing wooden districts is now out of question. Even more, the city strongly encourages innovative and modern buildings and now hosts several

innovative projects to showcase Finnish wood construction, with the Woodcity as a flagship programme.

This new landmark of Helsinki with green areas, playgrounds, and low-carbon buildings is also home to Finland’s largest wood building, which captures the CO2 equivalent of a year’s

driving for 600 passenger cars 4 and is home to Supercell, the famous and international Finnish video game studio.

Wood architecture is also used in the Central Library building, which was named Public Library of the Year (2019). Built to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Finnish independence, the building, named Oodi, is a strong calling card for Finish Wood architecture around the world. In fact, the Oodi Library represents a new type of library, offering the public different activities. The ground floor is in continuity with the Kansalaistori Square. The public space seems to continue within the building, once past the large entrance arch. The main facade of the library is made entirely of red fir wood and consists of prefabricated modules made using 3D parametric design. The first floor is organised around small, closed spaces: work areas for small groups of people distributed throughout the floor. Library users have access to recording studios with musical instruments, rooms dedicated to conferences or video projections, workstations and computers, a games area, a printing area with 3D printers, a kitchen, sewing machines and spaces for parties. On the other hand, the second and top floor of the building is dedicated to the library, which develops under an undulating cloud-shaped ceiling. In fact, the wood building is a first in Helsinki, and is made for local people to enhance their daily lives (research, experimentations, music, children’s activities, etc).

But, what do local people really think of wood? How do they picture and accept wood buildings in their neighborhood?

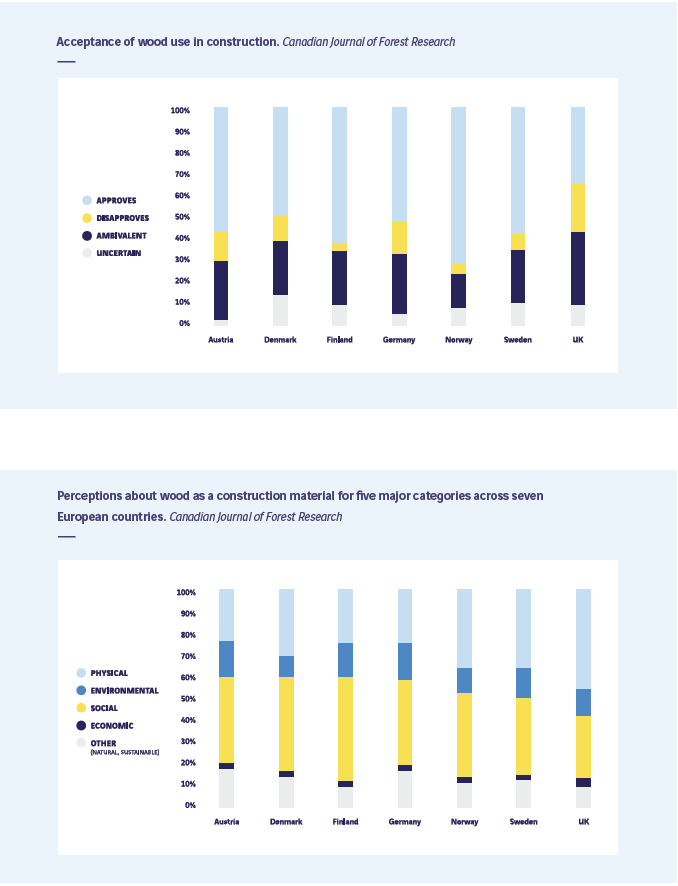

A unique study has been published in the Canadian Journal of Forest Research 5, measuring how people see wood buildings in the urban environment, based on several principles: its impact on national industry, urban aesthetic, environment and carbon emissions, and social life. In conclusion, the paper shows that in Finland, people are generally in favor of wood construction (before most of the other European countries), to defend tradition and aesthetic values. The environmental benefits come way after in the answers.

The garden city movement was a 20th century urban planning movement promoting satellite communities surrounding the central city and separated with greenbelts. These Garden Cities would contain proportionate areas of residences, industry, and agriculture. Ebenezer Howard 4 first posited the idea in 1898 to capture the primary benefits of the countryside and the city while avoiding the disadvantages presented by both.

Building the subterranean city

Today, the heritage value of basements and underground areas is little recognized. Often intended for industrial and technical use, the burial of urban activities has been a solution chosen to hide the “ugly” city, the urban backstage (sewers, waste treatment, power generation, underground transport). Yet several examples, and many in Helsinki, show the important value of underground space. In the 19th century, novels and journalists’ accounts of the expansion of cities into the suburbs (with the first metros) fed the social imagination in which the underground was the place of urban anti-capitalism, where the victims of this new mode of social organization were rejected.

The two world wars renewed the imagination of underground life, intended to protect populations from the risk of war, while the nuclear threat of the following years led to thinking about the survival of humanity, its cities and its functions, in the event of an attack. The first large-scale underground spaces came into being.

The construction of the vast underground network began in the 1980s and will continue in the coming years. According to the City of Helsinki, there are now 10 million square meters of underground spaces below the city and the uses are surprisingly diverse: a church, an art museum, swimming pools, go karting tracks, shops and even some civil defense shelters in case of war. According to Ilkka Vähäaho, the head of geotechnical division at the City of Helsinki, the underground life represents more than 400 premises, 220km of technical tunnels, 24km of raw water tunnels and 60km of ‘all-in-one’ utility tunnels (district heating and cooling, electrical and telecommunications cables, and water). One remarkable example is the famous Itäkeskus Underground swimming pool, which can welcome 1,000 customers at a time and can be converted into an emergency shelter for 3,800 people.

Another example is the not least remarkable Viikinmaki Wastewater Treatment Plant, which treats waste water for the entire City of Helsinki – and more. The urban expedition led us to the underground plant after a presentation of its origin and functioning. In fact, the plant is mainly built inside the rock and remains the largest wastewater treatment plant in Finland and the Nordic countries. The plant is very innovative: thanks to a dragging system based on gravity (it is sometimes 25 meters below sea level), it uses very few energy to move water along the tunnels. In fact, it is even more clever than that: the water biological treatment converts dissolved nitrogen into nitrogen gas, that is then reused for heating and electricity. Most of the retrieved waste is then converted into sludge, which is after dispatched all over the country for agriculture purposes.

In that example, going underground was not just a solution to hide the plant and protect the neighborhood’s calmness. It is also a solution to radically improve energy and heating consumption to the point of being almost self-sufficient.

Of course, many cities have their own underground spaces, connected to the transportation system or energy transfer. However, what’s typical to Helsinki is the integrated planning approach, based on the Helsinki Underground Masterplan. The document is at the basis of each underground land use and is often updated with new needs and developments. The first objective of the document is to keep some underground space aside, to accommodate future developments, such as tunnels, water and waste systems. As Jarmo Roinisto told us, having worked for the Underground department of the City of Helsinki, there are approximately forty rock spaces under reservation with no designated purpose yet. As an underground work is a one-off action (it is very costly and difficult to reseal a quarried space), the entire underground masterplan is resource-based, conceived in a way that ensures a development is at the right place and cannot be moved. Finally, efforts have been made in the Underground Masterplan to allow some underground spaces to be developed outside the underground city center area, where the stock of available spaces is scarce.

This new approach for underground planning has not only revolutionized city development and environmental protection. It has also changed the cadastral and property regulations, by creating a three-dimensioned document. A property is now defined by both its outdoor footprint and underground potential. This will help prevent any abuse and determine new stocks.

Based on a very precise and methodological approach that both preserves and develops the underground spaces, the City of Helsinki has seen many different uses grow in its entrails.

Some of them are internationally famous and were part of the learning expedition, such as the Temppeliaukio church, the Itäkeskus swimming pool or the numerous commercial galleries. However, there is one project that stands out from the others: the 100-kilometer tunnel that will link Helsinki and Tallin under the Gulf of Finland. The underwater tunnel will even entail the construction of one artificial island between the two cities, and would link them in 30 minutes (against 2 hours on a ferry). The project has now received a total of 15 billion euros from a Chinese company, which covers nearly all the construction costs. It is planned to open not before the end of 2024 at the earliest – if the approval process goes smoothly.

The environmental impact assessment is causing some delays with the Estonian government still refusing to sign the approval. Having signed a partnership with the China Railway Engineering Company, Peter Vesterbacka, founder of the company, claims the tunnelling works for the longest undersea train tunnel in the world would be very fast (around two years), largely supported by the experience of Finland in underground construction.

Today, about 50,000 Estonians are living in Finland. 20,000 more are working in Finland, and there are about 5,000 Finnish people living on the Estonian side. The tunnel is supposed to boost these numbers and support the relations between the two countries.

Helsinki has many particularities, both as a capital city and a harbor. The famous Finnish forest and timber competences are rooted into the city’s development, with buildings and districts showcasing local skills and innovation. From the prize-winning national library to the biggest wooden office building in Europe, Helsinki plays an important role in developing the Finnish timber tradition in the world.

The city is also very famous for its underground corridors, halls, and energy or transportation facilities. In fact, a whole city lies underground with its own churches, leisure activities and even swimming pools. Partly inherited from the wars Helsinki had to face during its construction, the underground city is now a rich source of solutions and innovations to accommodate urban development and climate change.

Overall, Helsinki shows a great potential of urban resilience and smart building. From the forest to its underground, there is plenty of inspiration. In fact, geo-thermal infrastructures, low-carbon buildings, and state-of-the art underground construction are all planned, built, and used with a particular approach : a smart and effective public/private partnership. The wood industry is perhaps the best example with its own national public program, supporting

local companies and international Finnish majors. It is time now to make sure France and urban planning have an ambitious public/ private approach to make sure the not-less ambitious carbon neutrality objectives are met.

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Lisbon beyond the Tagus

Forget 5th Avenue

A warm tomorrow

Long live urban density!

Behind the words: density

Toronto: How far can the city go?

Nature in the city

Inventing the future of urban highways

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.