Innovating in a constrained territory: perspectives on Singapore and Helsinki with Alistair Sim and Rikhard Manninen

In a context of climate change, the consequences of urban sprawl, which include growing pressure on natural environments and land resources as well as increasing CO2 emissions, have to be integrated into urban planning schemes. In 1965, as Singapore gained independence, the city, built on an island, found itself faced with limited natural and land resources. After intense verticalization and land reclamation works meant to accommodate its growing population and economic development, Singapore has started digging the ground for industrial and communications purposes. Also faced with a constrained territory and population growth, Helsinki published its first underground masterplan in 2010.

Rikhard Manninen, head of urban planning at the City of Helsinki, and Alistair Sim, regional director of Soletanche Bachy for the Asia Pacific Region, shared their cities’ experience of planning and land management in constrained territories during La Fabrique de la Cité’s urban expedition to Singapore, which took place from 10 to 12 July 2019.

What are the main constraints Helsinki and Singapore are facing in regard to their territory?

Alistair Sim: In Singapore, the most significant challenge is land scarcity. This explains why underground building is such an important part of the city-state’s strategy. Everything is done to maximize land use. The challenge consists not only in finding space for housing, transport, infrastructure, industry, etc. It is also about providing a green and pleasant environment. Interestingly, Singapore pays close attention to what cities around the world are doing. The city-state undertakes much research abroad before planning new projects. But Singapore has had an advantage in comparison to European metropolises, which must work and deal with already-existing infrastructure: it has had a clean sheet to work from. This advantage, however, is being eroded with the further underground infrastructure being planned in Singapore.

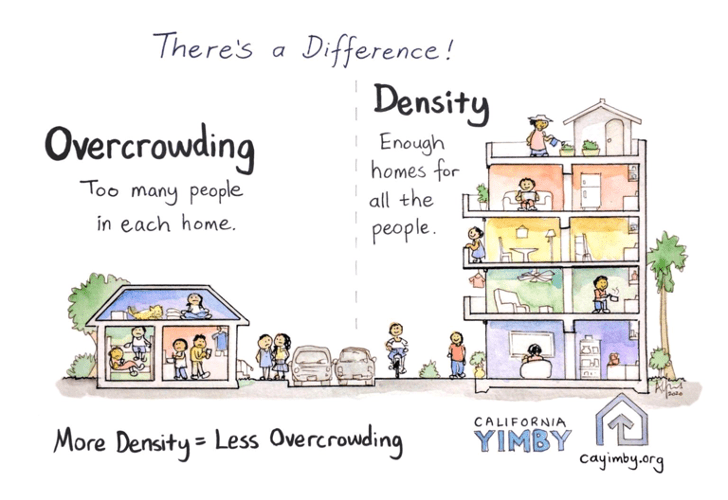

Rikhard Manninen: Land scarcity isn’t a major concern in Finland. However, the City of Helsinki is facing a challenging situation, as its city center is located on a peninsula and can thus not grow freely. In addition to this, all trends show that we must constrain urban expansion and hence build denser cities while dealing with a constant increase in population. Every year, about 17,000 additional residents move to the Helsinki region. This number is considerable in comparison with the overall metropolitan population of 1.5 million.

“The challenge consists not only in finding space for housing, transport, infrastructure, industry, etc. It is also about providing a green and pleasant environment”

– Alistair Sim

What are Helsinki’s priorities for the coming decades?

Rikhard Manninen: Helsinki, being Finland’s capital city, concentrates a major part of the country’s population and economic activities. It is necessary to take these elements into account when planning its future developments. In 2016, the Helsinki City Plan Vision 2050 was approved, which provides long-term vision (our focus year is 2050), and is purposely comprehensive: population projection, urban structure, urban economics, etc. We are now in the implementation phase, and, as head of urban planning, I oversee the detailed planning, including such transportation and traffic planning, in relation with the regional authority.

One of our major projects is focused on urban boulevards. As in other Western cities, several urban highways were built in Helsinki between the 1960s and the 1990s. These are run by the state, although the land is owned by the city. Both long disagreed on the future of these urban highways, eventually leading the Supreme Administrative Court of Finland to issue a decision partly in favor of Helsinki: two major roads are now being turned into urban boulevards, although the whole process will be long. Of course, technological development will help us, notably in dealing with some noise and air quality issues. Taking into account the new possibilities offered by technology, we aspire to promote increased use of electric vehicles, and the growth of our electric bus fleet is one of the City Plan’s priorities. The transformation of these urban highways into boulevards must be supported by the development of an attractive rail-based public transportation system.

Consequently, we have developed a vision of what the transportation system should be in 2050. In the city center, in addition to the already-existing metro lane, we are planning several light rail trams, one of which is already under implementation. There will be a commuter train system to connect the city center to the airport, which links Finland to the rest of the world. An underground city rail loop is also under planning, and a high-speed train will take you from Helsinki to Tampere, one of Finland’s largest cities, in one hour via Helsinki Airport. These are all developed in the framework both of a national l and a regional transportation plan that intend to tackle the problem of car dependency outside the city area and fight car-related CO2 emissions, which we aim to decrease by 50% by 2030. Our hope with these massive investments in public transportation is to create regional development.

“Our hope with these massive investments in public transportation is to create regional development.”

– Rikhard Manninen

Considering these constraints, to what extent can underground planning provide opportunities for cities?

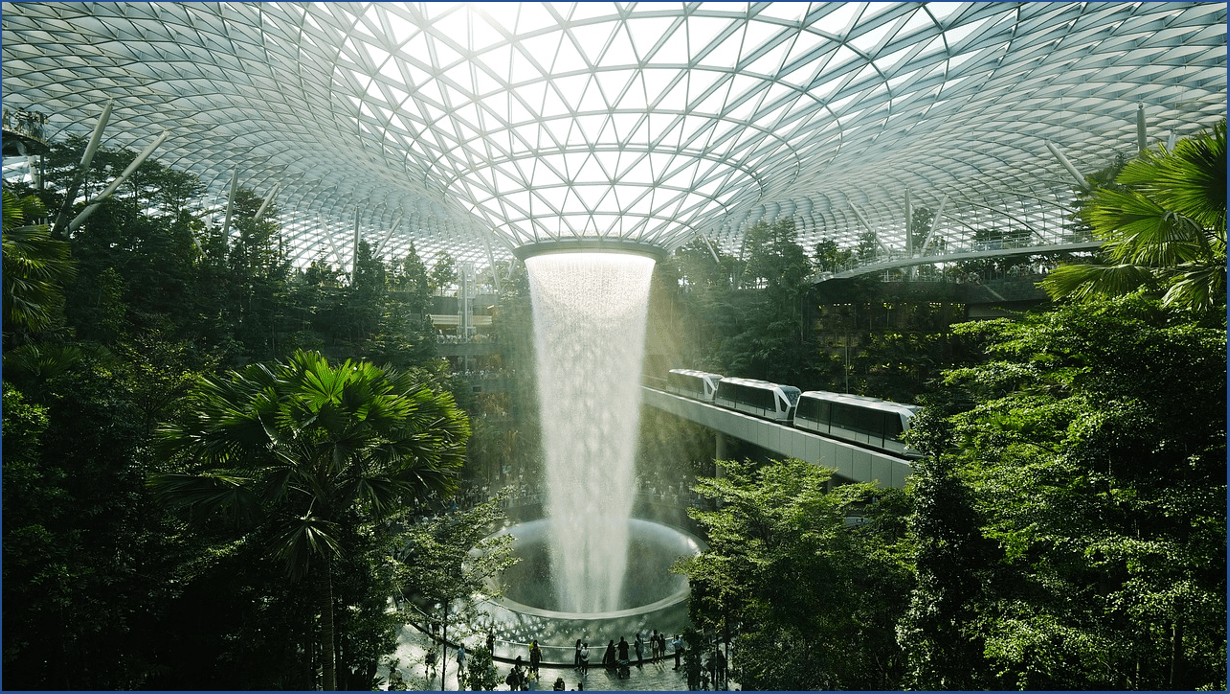

Alistair Sim: The underground is sometimes seen as an opportunity for people mobility. It can, in addition to this, be an opportunity for the transport of goods, especially in the Singaporean context, as it can provide routes from industrial areas to the ports. Generally speaking, the underground space has a much higher volume than the space above ground. So, because land scarcity is a major concern, Singapore is looking at all that can be done underneath the city. For example, the capture of used water and its transmission to central treatment points can be carried out underground. But the underground is not solely about utilities. A project linking both sides of Orchard Road – Singapore’s main commercial artery – provides underground shopping malls. ION Orchard perfectly exemplifies this aspiration: a four-level retail basement connects to the MRT (Mass Rapid Transit) station and to two below-road underground malls. Due to the climate, people tend to stay underground when they come out of the metro, underground shop properties are now very expensive – in the case of ION Orchard, retail space below-ground is now even more valuable than above-ground space. Generally speaking, underground construction in mature urban environments such as Singapore must consider the overall environment (context and various nuisances, including noise and dust), unforeseen elements, existing underground infrastructure, and the necessity of greater interconnectivity. Singapore’s government is also very concerned about security issues. If you travel on the MRT, you may notice that most of the stations have been Civil Defense shelters since the 1980s, which shows how much Singapore’s public authorities are concerned about the safety and security of the general public.

“Generally speaking, underground construction in mature urban environments such as Singapore must consider the overall environment […], unforeseen elements, existing underground infrastructure, and the necessity of greater interconnectivity.”

– Alistair Sim

Rikhard Manninen: Helsinki has also been working on its underground; our first underground masterplan was approved by the City Council in 2010. Like Singapore, our motivation is about taking advantage of all the space we can possibly use. For instance, we are now designing more underground pedestrian facilities than we used to. Furthermore, we are planning a large central tunnel that will be dedicated to car traffic. Yet we are faced with significant political debate, as some elected officials believe that this would attract cars into the city center instead of driving people to use public transportation. In other words, they think such an investment would go against our mobility strategy. At the planning level, we are taking this strategy into consideration and we will keep making suggestions to politicians, who will ultimately make the decisions. In any case, for this urban development to be sustainable, Helsinki is undergoing a massive transformation of its whole energy production system, which has direct impacts on its masterplan. By 2026, the city is to be completely independent from its current coal power plants, which implies finding new, effective technologies. Geothermic energy shows great potential and could be directly integrated into our new underground plan. Underground planning could also be thought of jointly with vertical planning, and we recently updated our underground masterplan to better integrate under- and above-ground developments. We now are in a process of continuously including all stakeholders in order to find new innovative solutions, including linked to verticalization, to tackle the challenges induced by urban growth. Nonetheless, the underground in itself is not a strategy for us. Some cities, such as Toronto or Montreal for instance, have huge underground networks under the city center. Helsinki does not.

“We now are in a process of continuously including all stakeholders in order to find new innovative solutions, including linked to verticalization, to tackle the challenges induced by urban growth [in Helsinki].”

– Rikhard Manninen

Building underground remains far more expensive than traditional construction. How does Singapore fund such work?

Alistair Sim: Thanks to rental revenues and taxes, the commercial part of Singapore’s underground strategy finds its economic balance. As for mass transit and road system costs, they should be considered with regards to Singapore’s car policy, since the levy system compensates for part of the investments. One must indeed keep in mind that, in order to own a car in Singapore, one must have a Certificate of Entitlement (COE) that is valid for a ten-year period. The Land Transport Authority will not increase the number of COEs available despite the rising population therefore their price, which relies on a bidding system, is expected to go up. Authorities have indeed decided to lower the vehicle growth rate from 0.25% per annum to 0%, with effect from February 2018. Moreover, car owners are required to pay an Additional Registration Fee, which varies according to the price of the vehicle, and can range between 100% for a car under S$20,000, 140% between S$20,001 and S$50,000, and 180% for a car over S$50,000. Overall, this has several consequences. On the one hand, it represents significant revenues for the state. On the other hand, the cost barrier of car ownership directly leads to high demand for public underground and above-ground transportation infrastructure.

To take full advantage of the underground space, knowledge about what is underneath is required. Do we have the right technology to map the underground?

Alistair Sim: We have good technology, but it does not necessarily tell us exactly where the facilities are, so when we arrive on site, we always have surprises. We discover lots of unexpected things in the underground.

Rikhard Manninen: We also have quite good data about the soil, but, as Alistair said, there is always something we don’t know about. When we extended Helsinki’s metro and had a section going underground and under the sea, we eventually had to move the building site slightly to avoid issues we had discovered. So, even with good technology, we are always surprised.

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Lisbon beyond the Tagus

Helsinki : Planning innovation and urban resilience

Forget 5th Avenue

Long live urban density!

Behind the words: density

Nature in the city

“Dig, baby, dig”

German metropolises and the affordable housing crisis

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.