Is soil artificialization the real enemy?

The fight against soil artificialization is at the heart of the proposals put forward by the 150 citizens selected to participate in France’s Citizens’ Climate Convention. It is also in the name of this fight that opposition to the EuropaCity commercial and leisure development project, suspended by the government last November, was structured. The concern appears justified when one reads that artificial soils represent about 10% of France’s surface area, that this ratio is only increasing, and that “over the past years, the equivalent of a départementhas been concreted[1]“. Artificialization contributes to the destruction of natural environments that provide ecological and ecosystem services which are “essential for our society: carbon storage, food and bio-based materials production, water purification, reduction of flood risk by infiltration, maintenance of natural landscapes, etc.[2]“. But what do we really mean by artificialization of soils? And is artificialization necessarily undesirable?

What is artificialization?

Gardens and parking lots

In France, the most commonly accepted definition of soil artificialization is the following, proposed by the Observatory for natural, agricultural and forest areas:

“A change in the actual state of an agricultural, forest or natural area towards artificial surfaces, i.e. urban fabrics, industrial and commercial areas, transport infrastructures and their dependencies, open-cast mines and quarries, landfills and construction sites, urban green spaces […], and sports and leisure facilities, including golf courses[3]”.

This extensive definition therefore considers green spaces like parks and gardens as artificial, even though they may have ecological value. At the same time, it considers natural, agricultural and forest areas that can sometimes be “polluted or deprived of their topsoil[4]“as not artificial. This definition thus precludes a precise distinction between areas with high ecological value and areas with weakened biodiversity, since, as France Stratégie explains, “it amounts to counting an urban park or a paved car park in the same way[5]“. It is nevertheless this definition that the French government uses when it talks of a 9.3% artificialization of the metropolitan territory; it is also the basis for the often-invoked idea of an artificialization rate leading to the disappearance of one départementper decade.

Divergent figures

There is, however, another, more restrictive definition of artificialization, used by the Eurostat agency, according to which “artificialized soils include built up soils and paved and stabilized soils (roads, railways, car parks, tracks, etc.)“.

The coexistence of these divergent definitions leads to significant disparities in the results of quantitative assessments of soil artificialization in France. While the definition adopted by the government, on which the annual “Teruti-Lucas” survey is based, shows an artificialization rate of slightly less than 10%, the European CORINE Land Cover survey, which is based on the Eurostat definition, evaluates the rate of soil artificialization in France at 5.6%, i.e. almost half as much!A report by INRA and IFSTTAR even notes that “the differences in measurement between the two sources range […] from 2% for Île-de-France[…] to more than 50% for regions that havebeen artificialized in a more limited and dispersed manner[6]“.

The two methods have one unfortunate point in common, however: they operate by extrapolation. Neither method covers the entire territory, thus illustrating the confusion that reigns around artificialization. Alice Colsaet (IDDRI) points out that “the various existing data[…] do not allow for comprehensive coverage of the territory or precise localization of the new artificial surfaces and does not offer satisfactory evaluation[7]“.It is therefore impossible, in the current state of the data collected, to distinguish different types or degrees of artificialization “according to the degree of impermeability or the impact on biodiversity[8]“.

These definitional difficulties are causing discord even in the debates on “zero net artificialization” (ZNA) conducted by the National Observatory of Soil Artificialization, founded by the government in 2019: “no clear definition of what ZNA is has been agreed upon,” explained a member of the working group to newspaper Le Moniteur at the end of the Observatory’s third meeting. “There can be no public policy without minimal agreement on the vocabulary[9].

A complex phenomenon, wrongly assimilated to “la France moche” (ugly France)

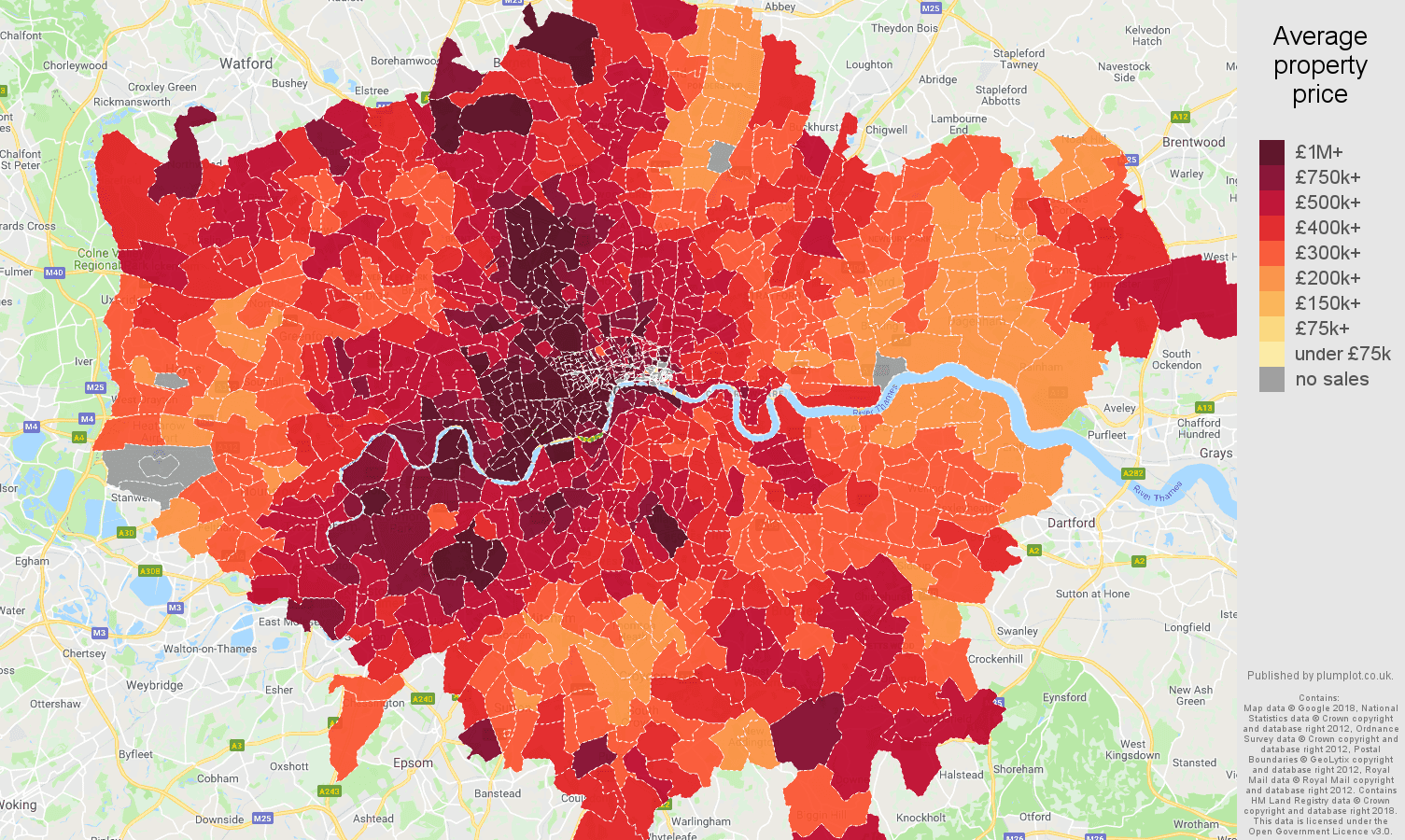

Often assimilated to peri-urbanization and the inevitable extension of an “ugly France”, soil artificialization actually covers complex realities and manifests itself differently from one territory to another. Thus, INRA and IFSTTAR point out that “soil artificialization goes well beyond the boundaries of the city and concerns more diffuse but no less significant peri-urban and rural areas[10]“. Alice Colsaet (IDDRI) proposes a typology based on four categories:

- “Very dense and artificial areas, rich, with strong demographic and economic growthand where artificialization is now slow(Parisian suburbs, Lyon region).

- Rather rural areas where demographic and economic growth is low or even negative, and where the progression of artificialization is below average(e.g., Ardèche, Cantal, Finistère).

- Departments where artificialization is strong, correlated with demographic and economic dynamism,often under the influence of a large city (e.g., Loire Atlantique, Gironde, Isère).

- Territories with a strong progression of artificialization, without strong demographic and economic pressure. This situation is the most worrying; it concerns more than a third of the departments[11]“.

Corrèze, for example, is in the latter category, with a 13% increase in the rate of soil artificialization between 2006 and 2015, even though the population grew by only 0.4% over the same period. “The proportions are almost similar in Moselle, Haute-Saône, Pas-de-Calais, Alpes-Maritimes, Manche and Charente,[12]” notes Le Monde. France Stratégie states that “at the departmental level, we observe contrasting artificialization dynamics, with the least densely populated departments experiencing artificialization processes in isolated communes, while very dense departments are essentially artificializing in the major urban centers and their crowns[13]“.

It thus seems impossible to associate an increase in artificialization with strong economic and/or demographic growth.

It should also be noted that the overwhelming majority of new construction does not involve land artificialization: a study of nearly 90% of all building permits issued in France between 2005 and 2013 showed that 42% of construction had been carried out “on already built areas, 26% in continuity with existing buildings, 24% by sprawl, and 8% by mass artificialization[14]“.

Finally, artificial surfaces are mainly used for housing:“nearly half of the artificial surfaces between 2006 and 2014 were used for housing[15]“, write INRA and IFSTTAR. According to France Stratégie, transport infrastructure (28% of the artificial surfaces observed) and service land (commercial and economic surfaces) come next (14%)[16].

France at war against soil artificialization

As early as the 1980s, French legal texts established restrictions on the concreting of certain natural landscapes. But it was not until the beginning of the 21stcentury that the fight against this phenomenon became a fully-fledged public policy objective. In 2000, the law on solidarity and urban renewal made the limitation of urban sprawl a priority. From then on, territorial coherence schemes (SCOT) and local urban plans (PLU) have had to determine “the conditions for ensuring[…] the economical and balanced use of natural, urban, peri-urban and rural areas“. Ten years later, a law passed on 12 July 2010 regarding the national commitment to the environment, known as “Grenelle II”, required SCOTs and PLUs to include an analysis of space consumption: “the law now assigns public authorities the task of ensuring effective control over the consumption of natural, agricultural and forest areas[17]“. In 2014, the law for access to housing and renovated urban planning, known as Loi Alur, included a chapter entitled “combating urban sprawl and the consumption of natural, agricultural and forest land“. The fights against soil artificialization and urban sprawl thus seem to merge and overlap perfectly. Four years later, the Interministerial Biodiversity Committee published a Biodiversity Plan, in which a new objective appeared: that of “zero net artificialization” (ZNA), i.e. the suspension of any net increase in artificialized areas.

This is a vast undertaking, as almost everything seems to encourage artificialization: Thus, as the Green Economy Committee points out, “(i) the local elected representative is faced with strong demands, in particular to extend constructability (…)(ii) the owner of agricultural land, because of the value of his plot of land made constructible, is encouraged to sell it for non-agricultural use, (iii) the developer, because of land prices and construction costs and regulatory rigidities, is encouraged to build in the periphery and in a low-density manner, while (iv) the household is encouraged to buy property in the periphery by the moderate cost and subsidies it may benefit from[18]“.

The pitfalls of a rigid vision of artificialization

The objective of “zero net artificialization”, an inoperative concept?

The public debate has taken up the issue of land artificialization without fully grasping its complexity, rejecting artificialization as a whole on the sole ground that it contributes to a loss of biodiversity, without taking into account that artificialization may sometimes be necessary, nor distinguishing between types of “artificial” land use or the territories and types of areas concerned.

The policy of “zero net artificialization” suffers precisely from insufficient consideration of complexity. Thus, the “ZAN” does not mean the end of artificial land use, but rather the need to “renature” artificial surfaces as new ones are artificialized. While this idea may seem logical and virtuous on paper, it clashes with the principle of reality: soils and their characteristics are not identical, or even similar, and are therefore not interchangeable at will.

Thus Thomas Cormier and Nicolas Cormet write that “this principle of interchangeability of artificial / non artificial surfaces is in reality not very operational. Most impacts cannot be compensated for: the disappearance of natural soil is an extremely long process (several centuries) involving natural processes (biological and climatic activity) that cannot be reproduced[19]“.

Beyond this first yet significant obstacle, is another question, regarding the scale at which ZNA must be achieved: is it at the national level? From one region, from one department to another? Alice Colsaet goes further: “its eventual implementation raises the question of political coordination[…] but also that of the economic model, because renaturation actions remain rare and costly for the time being[20]“. France Stratégie thus estimates the cost of renaturing artificial soil at 95 to 390 €/m2.

Much ado about nothing?

The terms of the public debate as they exist today tend to make artificialization of French soils appear much more important and widespread than it really is. In actuality, France is barely above the European average, while Europe itself is being artificialized much more slowly than other regions of the world. To give the right measure of the phenomenon, Éric Charmes explains that “at the rate of one department every year, it will take nearly three centuries before half of the French territory is artificialized[21]” and specifies that if all French households lived in peri-urban housing, the artificialization of land would still be only slightly higher than it was a few years ago; “and even if we added the 3 million second homes that currently exist, we would arrive at an artificialized surface area for metropolitan France of less than 11%[22]“.

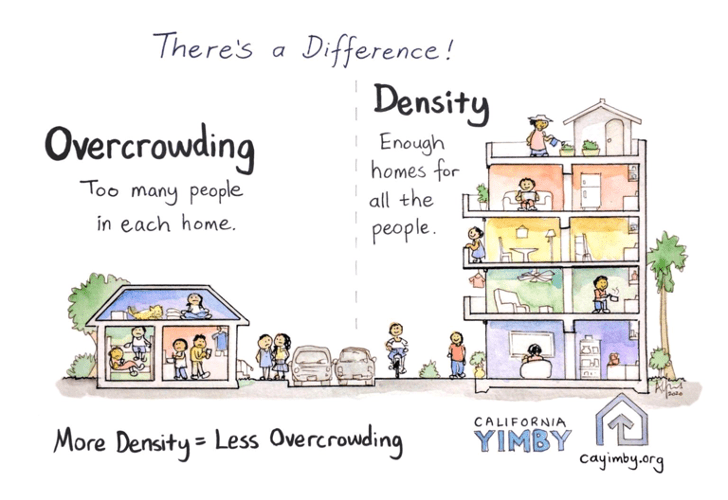

Moreover, the polarization of the debate on artificialization obscures the fact that not all artificialization is bad. On a global scale, population growth and continuing urbanization call for the construction of new housing and infrastructure, which will sometimes require the artificialization of land, even if artificialization for housing construction purposes is less justified in areas with a high vacancy rate than in areas with low vacancy rates and tight real estate markets. Here, the objective of preserving biodiversity comes up against an objective that can legitimately be considered to be equally in the public interest: meeting the demand for affordable housing by low- and middle-income households. Preserving the economic attractiveness of an area may also, to a certain extent, require the artificialization of land: “competition between communities to attract new inhabitants and businesses is a powerful pressure that conflicts with the objective of saving space[23]“, writes Alice Colsaet. Even more prosaically, INRA and IFSTTAR point out that:

“Artificial soils are at the same time the result and the place of human activities: it is the space of cities, housing, economic activities and the exchange networks between these places. It is therefore an essential societal space that meets the economic and social needs of households, businesses and public authorities, thus expressing the social utility of this use[24]“.

The contradiction between the necessary artificialization resulting from the needs of our societies and human interactions and the equally necessary preservation of biodiversity and the environment plays out even in legal texts: thus, at the time when the Grenellelaws mentioned above were promulgated, the law on the Greater Paris also came into force, setting quantified objectives for housing production[25].

Is fragmentation the real enemy?

This contradiction disappears when we consider artificialization no longer in quantitative terms but rather in qualitative terms. Éric Charmes already called us to it in 2013, when he wrote that artificialization is almost exclusively presented as synonymous with urban sprawl, but it can also be a densification of rural areas[26]. He concluded that it is not artificialization that threatens territorial equilibrium, but fragmentation: “the focus on quantitative aspects puts a veil over what really poses a problem, namely the form taken by urban and peri-urban sprawl and the way in which it is organized[…] it is less the disappearance, relatively limited in any case, of agricultural land that poses a problem than the nature and location of artificial land and especially the urban sprawl of rural territories[27]“. Thus, as far as metropolises are concerned, the peri-urban fabric is now growing in a fragmented rather than in a uniform sprawl: “the artificial surfaces of each peri-urban commune generally remain separate from the artificial surfaces of neighboring communes[28]“. However, recalls Éric Charmes, “if urbanization were to take place exclusively by continuous sprawl, in continuity with the boundaries of French metropolises, its impact would be much less than with current forms of peri-urbanization[29]“.

In the case of agricultural land, fragmentation is a sign of the multiplication of points of contact with artificial soil and therefore amplifies the effects of artificialization. For households, fragmentation also means increasing distance between housing and employment areas, requiring the use of cars, which places a significant burden on household budgets. “The agricultural world is mistaken in calling for an end to artificialization,” concludes Éric Charmes. “It would be wiser to call for better organization of urban extensions and better planning[30]”. Charmes warns against the pitfalls of “land Malthusianism[31]“, “a source of functional urban sprawl and a contributor to the housing crisis[32]“. A word to the wise!

[1] Rémi Barroux, L’artificialisation des sols progresse, même sans pression démographique et économique, Le Monde, 13 March 2019. URL:https://www.lemonde.fr/planete/article/2019/03/13/l-artificialisation-des-sols-progresse-meme-sans-pression-demographique-et-economique_5435447_3244.html

[2] Thomas Cormier, Nicolas Cornet, Zéro artificialisation nette, un défi sans précédent. Note rapide n°832, Institut Paris Région, janvier 2020.

[3] Sols artificialisés et processus d’artificialization des sols : déterminants, impacts et leviers d’action, résumé de l’expertise scientifique collective, INRA, IFSTTAR, December 2017.

[4] Thomas Cormier, Nicolas Cornet, Zéro artificialisation nette, un défi sans précédent. Note rapide n°832, Institut Paris Région, January 2020.

[5] Julien Fosse, Objectif « zéro artificialisation nette » : quels leviers pour protéger les sols ?, France Stratégie, July 2019. URL: https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/sites/strategie.gouv.fr/files/atoms/files/fs-rapport-2019-artificialisation-juillet.pdf

[6] Sols artificialisés et processus d’artificialisation des sols : déterminants, impacts et leviers d’action, résumé de l’expertise scientifique collective, INRA, IFSTTAR, December 2017.

[7] Colsaet. A. (2019). Artificialisation des sols : quelles avancées politiques pour quels résultats ? Iddri, Décryptage N°02/19.

[8] Julien Fosse, Objectif « zéro artificialisation nette » : quels leviers pour protéger les sols ?, France Stratégie, July 2019. URL: https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/sites/strategie.gouv.fr/files/atoms/files/fs-rapport-2019-artificialisation-juillet.pdf

[9] Sandrine Pheulpin, Le groupe de travail « artificialisation des sols » peine à trouver un consensus, Le Moniteur, 12 December 2019. URL: https://www.lemoniteur.fr/article/le-groupe-de-travail-artificialisation-des-sols-peine-a-trouver-un-consensus.2067849

[10] Sols artificialisés et processus d’artificialisation des sols : déterminants, impacts et leviers d’action, résumé de l’expertise scientifique collective, INRA, IFSTTAR, December 2017.

[11] Colsaet. A. (2019). Artificialisation des sols : quelles avancées politiques pour quels résultats ? Iddri, Décryptage N°02/19.

[12] Rémi Barroux, L’artificialisation des sols progresse, même sans pression démographique et économique, Le Monde, 13 March 2019. URL: https://www.lemonde.fr/planete/article/2019/03/13/l-artificialisation-des-sols-progresse-meme-sans-pression-demographique-et-economique_5435447_3244.html

[13] Julien Fosse, Objectif « zéro artificialisation nette » : quels leviers pour protéger les sols ?, France Stratégie, July 2019. URL: https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/sites/strategie.gouv.fr/files/atoms/files/fs-rapport-2019-artificialisation-juillet.pdf

[14] Julien Fosse, Objectif « zéro artificialisation nette » : quels leviers pour protéger les sols ?, France Stratégie, July 2019. URL: https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/sites/strategie.gouv.fr/files/atoms/files/fs-rapport-2019-artificialisation-juillet.pdf

[15] Sols artificialisés et processus d’artificialisation des sols : déterminants, impacts et leviers d’action, résumé de l’expertise scientifique collective, INRA, IFSTTAR, December 2017.

[16] Julien Fosse, Objectif « zéro artificialisation nette » : quels leviers pour protéger les sols ?, France Stratégie, July 2019. URL: https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/sites/strategie.gouv.fr/files/atoms/files/fs-rapport-2019-artificialisation-juillet.pdf

[17] Charlotte Denizeau, Le nouveau PLU issu de la loi Grenelle II : densifier, sans s’étaler !, Métropolitiques, 4 April 2011. URL: https://www.metropolitiques.eu/Le-nouveau-PLU-issu-de-la-loi.html

[18] Les enjeux de l’artificialisation des sols : diagnostic. Comité pour l’économie verte. URL: https://www.ecologique-solidaire.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/Les%20enjeux%20de%20l%E2%80%99artificialisation%20des%20sols.pdf

[19] Thomas Cormier, Nicolas Cornet, Zéro artificialisation nette, un défi sans précédent. Note rapide n°832, Institut Paris Région, January 2020.

[20] Colsaet. A. (2019). Artificialisation des sols : quelles avancées politiques pour quels résultats ? Iddri, Décryptage N°02/19.

[21] Éric Charmes, L’artificialisation est-elle vraiment un problème quantitatif ?, études foncières n°162, March-April 2013.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Colsaet. A. (2019). Artificialisation des sols : quelles avancées politiques pour quels résultats ? Iddri, Décryptage N°02/19.

[24] Sols artificialisés et processus d’artificialisation des sols : déterminants, impacts et leviers d’action, résumé de l’expertise scientifique collective, INRA, IFSTTAR, December 2017.

[25] Alexandra Cocquière, De la maîtrise de l’étalement urbain à l’objectif « zéro artificialization nette », Note rapide, Institut Paris Région, February 2020.

[26] Éric Charmes, L’artificialisation est-elle vraiment un problème quantitatif ?, études foncières n°162, March-April 2013.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Lisbon beyond the Tagus

Helsinki : Planning innovation and urban resilience

Forget 5th Avenue

Long live urban density!

Behind the words: density

“Dig, baby, dig”

German metropolises and the affordable housing crisis

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.