Is the ability to live in a city a key factor of quality of life?

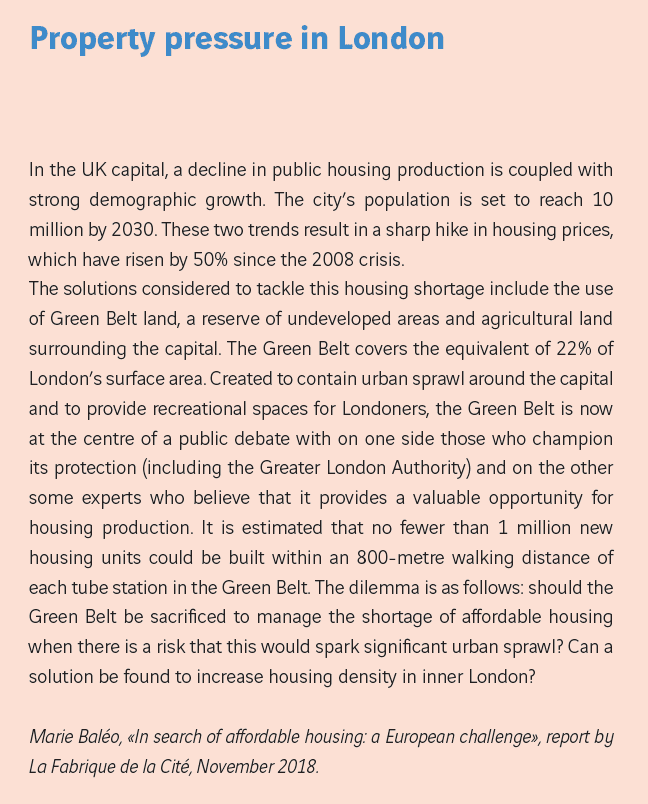

The demographic growth recorded by European cities is currently causing major tension on the property market. Property prices are soaring, the amount of available land is falling and there is a decline in social housing stock following successive rounds of privatisation. Socio-spatial fragmentation is on the rise, resulting in segregation. Housing in cities is becoming inaccessible to some and those who do have access are suffering from the rising prices and are experiencing a drop in quality of life. Housing, as a key factor of the private sector and the basis of quality of life, acts as a springboard towards the public sector and an open vision of the world. Many aspects of our lives depend on housing: employment, education, social relationships, economic status, all major determinants of quality of life. It is therefore necessary to be able to provide housing for all and the right to housing, considered as a necessary condition for individual development, is fundamental. During its 2018 international seminar held in Vienna, La Fabrique de la Cité met with different French and international housing stakeholders to debate the way in which housing can be and can remain a key element of quality of life in cities, despite the challenges it faces.

Housing for everyone: the challenge for growing European cities

Ensuring that everyone has housing in cities undergoing strong demographic growth is a major challenge. Municipalities must create sufficient housing supply to reduce the existing tension on the market and provide affordable housing for all. A study conducted by La Fabrique de la Cité on affordable housing in major European cities experiencing population growth highlights the different strategies implemented by the city councils of Bordeaux, Stockholm, Berlin, Munich, Paris and Warsaw to tackle the shortage. The avenues explored include housing construction methods that would result in swifter and less expensive production. In Stockholm, the company tasked with building municipal housing opted for a standardised construction method to produce housing units at a cost 25% lower than the market cost.

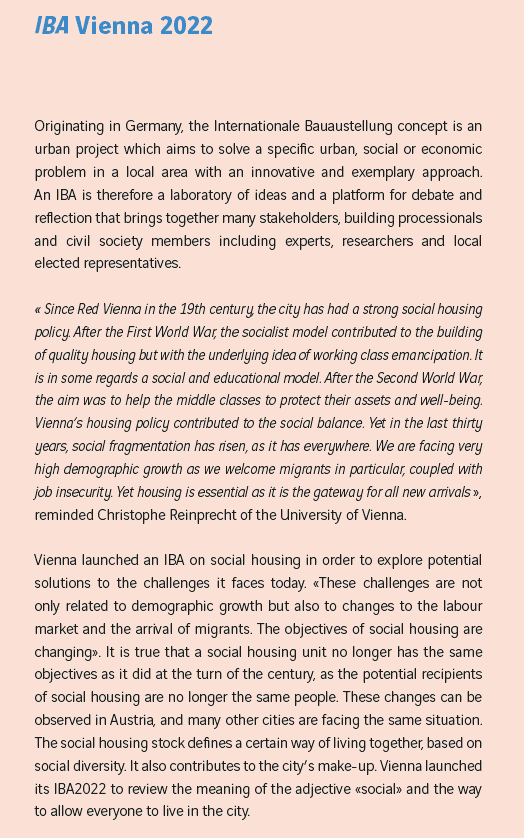

Vienna is a counter-example in the European overview. The Austrian capital welcomed 30,000 new arrivals[1] in 2016 and yet housing remains affordable in the city. “The city of Vienna has inherited an affordable housing philosophy that goes back more than a century“, explained Kurt Puchinger from the office of the executive municipal councillor for housing in Vienna. “In Austria, housing is regulated on a federal level. 65% of the Viennese population live in housing subsidised by the city council. This situation results in a moderation of prices on the private market. Out of a housing stock of around 1 million units, there are more than 220,000 municipal housing units”. Vienna city council has decided to retain part of its housing stock and to continue to provide public housing. In addition, the city has now set itself the objective of building some 9,000 social housing units each year.

“If you think of housing as an asset among others, there will not be any solution to deal with the crisis facing major cities. On the other hand, if housing is considered to be a basic right, there will always be a solution”, claimed Gil Peňalosa from 8-80 Cities. This may be one of the secrets of the city of Vienna, which believes that “housing is a human right and is essential for all citizens”, as Kurt Puchinger confirmed. The solutions that need to be implemented to provide affordable housing that gives access to the city and its amenities to all are complex, however, and political will is key, claimed Audrey Linkenheld, head of development and partnerships at Vilogia and local councillor in Lille. “Assertive policies must be rolled out and we must have ambitious urban projects but, in spite of this, we are struggling to find housing for refugees, for the homeless and for the most underprivileged while there is great insecurity in some districts”. Vienna illustrates the importance of this political will: the city council allocates roughly €100 million per year to housing subsidies. “One solution we have implemented is unlimited tenancy agreements to avoid evictions“, stated Kurt Puchinger. If housing is to be considered as a special asset, which regulations can be implemented to ensure access for every person? Must all housing units be subject to the same regulations and systems?

Ensuring housing quality

Having somewhere to live is one thing, having quality housing is quite another. “Nobody wants to live in a shoebox”, insisted Georg Niedermühlbichler from Vienna city council. “Housing is the most important element of quality of life because we spend a lot of time in it and feel at home there”. The issue of housing quality is very broad and encompasses different aspects ranging from the intrinsic quality of the housing to the quality of the environment that it offers and helps to create.

“Housing stock must be maintained in good condition”, confirmed Kurt Puchinger. “However, to avoid gentrification and exclusion, we have adopted a soft renovation principle so that people can remain in their housing after renovation”. The materials selected are also crucial for indoor air quality and therefore have an effect on residents’ health. Housing quality also entails adapting it to the residents’ requirements. In Bordeaux, the city council decided to build housing units for which owners must complete the finishing touches (“volumes capables”): this solution cuts building costs and spaces are modulated according to requirements. “In Lille, one of the challenges is to be able to meet families’ needs. Housing in Lille is too small for families and rent is too expensive. To build quality housing, requirements must be considered, particularly in terms of size”, explained Audrey Linkenheld.

While the intrinsic quality of housing is fundamental, interactions between housing and its environment are just as important. “Vienna city council strives to provide services and social infrastructure such as nurseries and playgrounds near housing”, continued Kurt Puchinger. The question of housing accessibility is also crucial. Does housing provide access to the necessary conditions for individual development? Access to urban amenities such as jobs, recreational activities and health providers must be guaranteed through transportation. The accessibility of housing goes hand in hand with its residents’ possible mobility but the effect of the address and influence of the housing location on individuals’ life paths must also be considered. To avoid all forms of residential stigmatisation, a dynamic local area is key. This is why, in a study on residential mobility in Lille and Roubaix[2], Yoan Miot claims that “housing stock action cannot be dissociated from action in favour of employment and the economic development of the local area”. The policy rolled out in the new Seestadt district of Vienna aims to meet these challenges. This district will ultimately host 20,000 inhabitants and as many jobs. “Vienna has tried to build a city where people can live and work. Another guiding principle of the project is to ensure that inhabitants also have access to the surrounding environment in their free time”, specified Christrophe Reinprecht, from the University of Vienna. Housing goes beyond the framework of private housing and “the housing’s demand on the environment is increasingly strong”, claimed Audrey Linkenheld. “Inhabitants want to enjoy urban amenities but everyone wants to be near green areas and, ultimately, to be able to benefit from amenities without suffering any restrictions”. How can these two dimensions be coordinated to create housing that gives rise to well-being?

Having somewhere to live or actually living?

“The issue of housing is not just about four walls” according to Christophe Reinprecht. To use the words of Martin Heidegger, living means “being present in the world and for those around us”. Having accommodation is not living. The act of living has an existential dimension. The presence of people on earth is not about the number of square metres of housing or the architectural quality of a residential building”[3]. Having access to housing is therefore a means of taking ownership of the environment and it gives us the ability not only to be but also to act, which is a key factor of quality of life as defined by Amartya Sen. The quality of the private sphere is a springboard towards involvement in the public sphere and city life. “Having accommodation means being a citizen of a city. In reference to the distinction that Henry Lefebvre makes between ‘Habitant’ and ‘Inhabitant’ it can be said that if we live in the city, we are no longer a mere ‘habitant’ but really become a ‘participant’ in the city”, commented Christophe Reinprecht.

Housing is therefore the foundation in our discovery of the world around us and our participation in city life. Housing quality is also determined according to its ability to allow inhabitants of the city to live together. The question of social diversity is raised in this regard. “What is social diversity? In a general sense, we believe that it is not good to have rich districts and poor areas. Yet this vision can be turned around to say that districts of integration are a means of households moving towards a less precarious status – and local area”, according to Yves-Laurent Sapoval, advisor to the Director of housing, urban planning and landscapes at the French Ministry of Ecology, Sustainable Development and Energy and the Ministry of Housing and Sustainable Housing. If all local areas operate well and allow each person to have optimal life paths, should social diversity be forced? Can it hinder the emergence of solidarity within the community? “The main problem with diversity is its scale. It is a key issue that we must analyse and come back to. In 2016, the German pavilion at the Venice architecture biennale focused on this question of scale in social integration”, explained Yves-Laurent Sapoval. Vienna city council spearheaded social diversity in its housing policy as a guarantee of universal integration. “Vienna’s housing policy is a great success because it contributes to the city’s social balance. Diversity contributes to the creation of a feeling of city life”, stressed Christophe Reinprecht. Housing appears to be the foundation of the right to be a city citizen. How can policies be rolled out to promote this idea of actually living in the city? How can access to decent housing be guaranteed for all while ensuring that the local area does not hinder individuals’ life paths? The challenge of housing therefore goes beyond its simple physical aspect. It is central to the challenges that growing major cities are facing to guarantee quality of life, which is essential to give inhabitants the ability to be and the freedom to act.

[1] JOE CORTRIGHT “Housing policy lessons from Vienna – Part I” http://cityobservatory.org/housing-policy-lessons-from-vienna-part-i/

[2] YOAN MIOT “La ségrégation socio-spatiale dans la métropole lilloise et à Roubaix : l’apport des mobilités résidentielles » Géographie, économie, société (2012) (in French)

[3] THIERRY PAQUOT « Introduction. « Habitat », « habitation », « habiter », précisions sur trois termes parents. » Thierry Paquot et al. Habiter, le propre de l’humain. P.7-16 (in French)

Find this publication in the projects:

-

Quality of life beyond labelsSmart cities, sustainable cities, green cities... What is the reality behind those labels ?

Quality of life beyond labelsSmart cities, sustainable cities, green cities... What is the reality behind those labels ? -

Affordable housing in growing European metropolisesHow can growing European metropolises, faced with scarce, expensive land and rising construction costs, provide enough affordable housing to accommodate the needs of low-income households?

Affordable housing in growing European metropolisesHow can growing European metropolises, faced with scarce, expensive land and rising construction costs, provide enough affordable housing to accommodate the needs of low-income households?

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

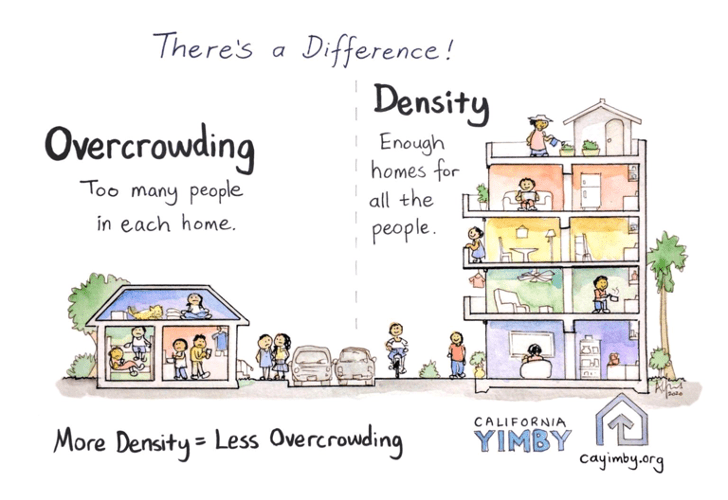

Long live urban density!

The ideal culprit

Behind the words: density

Behind the words: Affordable housing

Viktor Mayer-Schönberger: what role does big data play in cities?

Thomas Madreiter: Vienna and the smart city

German metropolises and the affordable housing crisis

Vienna

Breathless Metropolises

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.