Nature in cities: a conversation with Philippe Clergeau, Lim Liang Jim and Michèle Larüe Charlus

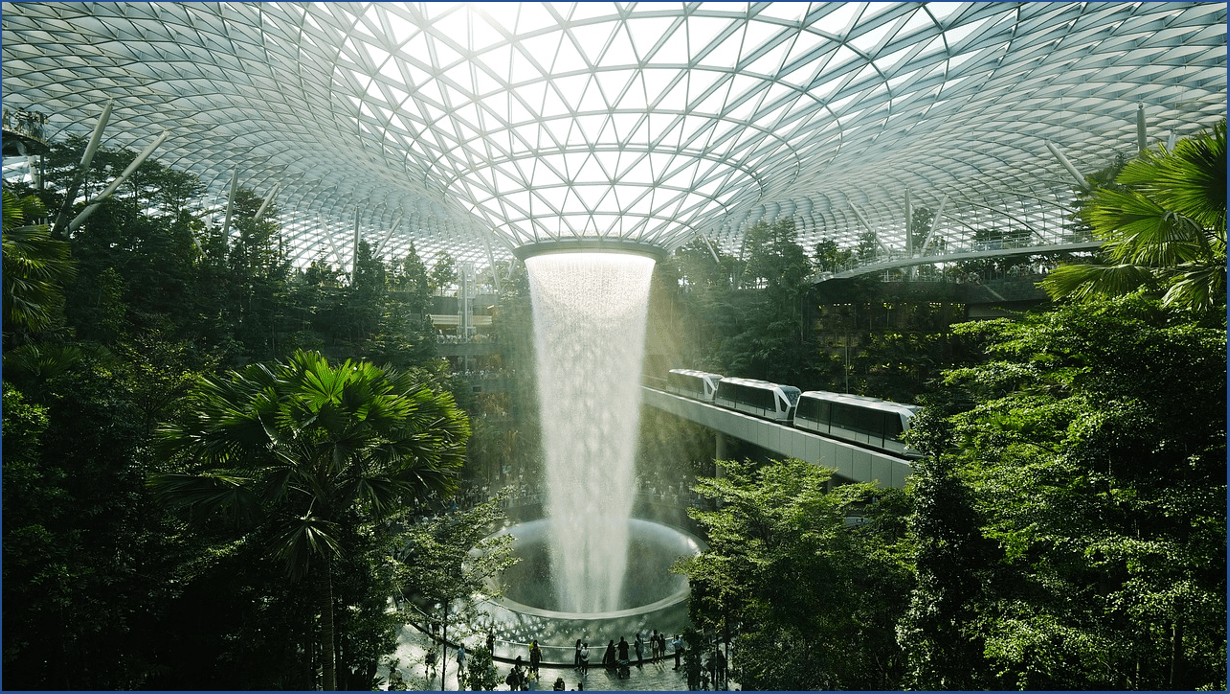

From 10 to 12 July 2019, La Fabrique de la Cité organized an urban expedition to Singapore, during which it welcomed Philippe Clergeau, a professor at the Paris National Museum of Natural History, Lim Liang Jim, director of the National Biodiversity Centre at the National Parks Board, and Michèle Larüe-Charlus, head of the #BM2050 mission at Bordeaux Métropole, for a debate on the place of nature in cities. How can nature and biodiversity be integrated into the urban environment? The restoration of biodiversity serves as a tool to enhance a territory’s resilience and optimize resource management. How can we enhance the production of ecosystem services? Finally, as Singapore pursues a “biophilic city in a garden” target, can it really become the conservatory of natural ecosystems?

How do you define nature and biodiversity?

Philippe Clergeau: Nature is a broad term that encompasses living being as well as minerals and habitats. Biodiversity is the natural diversity of living organisms. This is not so much a matter of variety, but rather is about the functioning it engenders and the relationships between species. A flower pot is not biodiversity. However, if a bee comes along to gather pollen and further pollinate, then there is functioning. Biodiversity is characterized by stability and sustainability. Nowadays, the main challenge is not about greening, which we are already able to do. The transition towards more biodiversity cannot be limited to planting in order to get hedgehogs to come into cities. A biodiversity-based approach must take into account local species. The transition implies that we ensure its sustainability; by this, I mean efficient and virtuous management involving specific stakeholders and technics, not to mention reinvented modes of governance that are able to foresee potential events.

Lim Liang Jim: Nature and biodiversity are different, although related, matters. Nature encompasses not just plants, animals and their products – but critically includes the landscape. Consequently, a place can be very natural, and yet, have very low biodiversity. Alaska is a perfect example; it is one of the most natural places in the world if you take into account its landscape (the mountains, valleys, rivers and glaciers), still, its biodiversity cannot be compared to Singapore’s. Indeed, biodiversity has a great deal to do with climate. It is undeniable that the highest biodiversity is concentrated in the tropics. Biodiversity – the flora, fauna and the ecosystems in which they occur – provides a wide range of ecosystem services which include coastal protection, carbon storage, microclimate cooling, air purification, water regulation, waste treatment, food and nutrient cycling, mental and physical health, and recreation. That said, we still consider biodiversity and ecosystem services in a very anthropocentric way – what can biodiversity and nature do for us, rather than considering humans as part of a larger ecosystem where both nature and humans provide equal benefits to one another.

What is Singapore’s strategy to enhance biodiversity and nature in the city?

Lim Liang Jim: Singapore has a very specific historical and geopolitical context. It was originally a large primary rainforest. But, as you know, in the 19th century, Singapore was colonised and forests were converted to agricultural land for spices. Consequently, about 90% of our forests were turned into farmland, especially for pepper and gambier plantations by the early 1900s. Ever since Singapore’s independence in 1965, we’ve had a stable political regime with a strong political will to green the city. Lee Kuan Yew, the city-state’s first prime minister, made an iconic statement about a clean and green Singapore. This vision has changed over the years. Today, we are pursuing a “biophilic city in a garden”; nature and access to nature are important, but it should also be about community, engagement, and connection. However, reference to a “garden” implies a control and management of greenery, plants, and animals. There is still a lot of anthropogenic input into maintaining a garden. What we ultimately want to work towards is “a city in nature”, whereby there is harmony and balance between the natural elements of the city, the hard elements, and the human elements.

Apart from political stability and consistent vision, we need a masterplan. Our Nature Conservation Masterplan comprises four categories of action.

The first one is conservation of key habitats. This deals with the establishment of nature reserves: the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Central Catchment Nature Reserve, Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, and Labrador Nature Reserve. We also manage the Sister’s Island Marine Park, in the Southern Islands. All these reserves feature our key ecosystems. To keep human activities at the margin of these core areas, buffer zones, in the form of Nature Parks, have been implemented.

We also complement these nature reserves with a comprehensive network of green spaces that help link animals – in particular flying species like birds, bees, butterflies, and other pollinators – from one green node to another. These are called Nature Ways. They serve as ecological corridors and networks and provide a naturalistic planting palette to integrate greenery in the city. Our ecological corridors are planned using computer modelling, based on the ecological requirements of certain target species.

In addition to all that, nature is integrated within the urban environment through vertical and rooftop greening. Indeed, Singapore had a fortunate realization that we have no hinterland to play around with. Hence, we decided very early on to innovate to make sure that greenery occurs on every level of human infrastructure. We now have more than 100 ha of skyrise greenery, planted in a multi-layered fashion in order to appeal to animals of all types, and we green bridges and other types of infrastructure.

Second is habitat enhancement, restoration, and species recovery. Habitat enhancement and restoration consist in weeding out invasive introduced plants and turning abandoned farmland back into forested areas. This goes hand in hand with species recovery, whereby we aim to recover the populations of 100 rare and endangered species. One recent success story is that of the oriental pied hornbill, once extinct in Singapore, returned in the 2000s, and there are now more than 100 individuals in the city.

Third comes applied research in conservation biology and planning. Credible research is the foundation behind our conservation efforts. The National Biodiversity Centre has a research and breeding programme for the highly endangered Singapore freshwater crab and has succeeded in the captive breeding of close to 300 young crabs – almost 50% of the wild population in Singapore. We discovered very interesting behaviours about some bird species based on satellite-tracking: we know where they go in Singapore and outside of Singapore. The next step is to apply environmental DNA, drones, and acoustic sensors. Together with population modelling, hydrology modelling and agent-based modelling, these tools will allow us to carry out our research in a much more efficient manner.

The last pillar is community stewardship and outreach in nature. Involving children is very important, in order to get them to appreciate nature early and make them understand that nature is part of Singapore’s DNA. Our projects not only involve children but also families, citizen scientists, corporations, and academics. The people must be involved: social impetus will continue to complement the political will for a city in nature.

Philippe Clergeau: Singapore is a very specific case. Being a city-state, it goes beyond the boundaries of the mere city. Its originality consists in managing a city, its peri urban areas, and even more, as Jim mentioned, forest and marine reserves. Yet the protection of these habitats depends on very different management approaches.

The geographical and climatic situations of Singapore and European cities are not comparable. As mentioned by Jim, the closer to the tropics, the more species one can find. A humid climate also tremendously favours planting: any planted seed can grow in it. In Europe, it is necessary to water, abundantly and frequently. It is however obvious that we do not have the same approach to biodiversity!

The people must be involved: social impetus will continue to complement the political will for a city in nature.

– Lim Liang Jim

The notion of garden implies anthropogenic input and human-centric approach. Despite this aspect, what are cities’ responsibilities in fighting loss of biodiversity?

Philippe Clergeau: In France, 20 % of the territory is considered urban. It is therefore clear that cities have a responsibility to protect nature. Yet we are still in the early stages of introducing nature into the city. Cities have never opened their arms to nature. There have always been pigeons and rats, but this will to let nature enter cities for very anthropocentric service functions only dates back to the 19th century for public health considerations. Ecosystem services and health are becoming strong arguments when it comes to this question. However, how can we go further and head towards eco-centrism?

We have started greening our cities; still, transitioning towards biodiversity implies a more complex approach of the ecosystem functioning of nature. By allowing certain species to settle, we will protect them. But what species should we favour? We must not forget that many uncommon species will never come to cities, and that many others are not accepted by city-dwellers – large mammals or insects – and indeed have nothing to do in cities. It is therefore clear that cities are not the future of biodiversity.

This matter of responsibility also raises a question about scales. How can we host species and avoid others (mosquitos, etc.)? We know how to plant, but welcoming local plants and integrating them within a regional functioning is more complicated. Let me insist on the notion of “regional”, as cities must not be considered intra muros. I believe the future of the urban environment is playing out in peri urban areas, because that is where urban sprawl is managed.

Finally, how will geography and ecology be able to structure urban planning? In Europe, when a housing estate is being built, the whole plot is razed to construct houses and roads, while keeping three trees. I am barely exaggerating. Today, some urban planners are starting to look at slopes, flows, natural reservoirs, and at where species are settled before developing. This nonetheless implies a whole new paradigm and remains only a utopia for many people.

Michèle Larüe-Charlus: This question of scales is extremely relevant. We asked Électricité de France (EDF) – France’s main electricity supplier – if Bordeaux could be carbon-neutral by 2050. We were told that this could not be done, as we did not even know how to compensate the current increase in CO2 emissions. One sixth of the Landes forest – Europe’s largest forest, planted in the 19th century – should be integrated into the territory in order to achieve this target. Hence, beyond administrative boundaries, what scales must we consider? The regional scale is too wide, but a scale that would include surrounding départements – country subdivisions – and allow us to work on carbon neutrality with neighbouring medium-sized cities, forest and agricultural reservoirs can be envisaged. I believe decision-makers have understood that metropolises cannot be self-sufficient. In the future, cities will need their hinterland more than hinterlands needs cities. Without this awareness, we will not be able to manage this issue.

Lim Liang Jim: I believe that, beyond all the benefits nature provides, we have a responsibility to conserve at least the value of our natural heritage. Human beings are always up in arms when a building is threatened with demolition. But unlike these structures which can be built up the same as before, mother nature is a very patient engineer. When you tear down a jungle, it takes millions of years to come back.

What is the political project that lies behind the idea of nature in cities?

Lim Liang Jim: In Singapore, the context is simple – effective governance, with strong involvement from the community. In the old days, the management of animals, for example, outside of the boundaries of nature reserves did not come under the purview of my agency but another one. We recently merged these two entities to further integrate our approach to biodiversity conservation. Our first challenge is to make everyone understand that greening our city is important even though we are a densely-populated city. I believe Singapore is one of the only places where you can find six million inhabitants in 721 km², with one of the highest GDPs in the world, and yet so green and so lush. Yes, Singapore is constrained by its territory. However, despite this constraint, we understood that we must provide a healthy environment for people to live in and our economy to grow. I think that commitments to integrating nature within the urban space and with urban infrastructure as well as the understanding of the positive outcomes of these commitments will benefit you and future generations.

Now, we have learnt to value nature. A valuation exercise was initiated recently with the Future Cities Laboratory’s Nature Capital project about ecosystem services. This angle is very interesting and will help strengthen the value proposition of greenery and nature to a city. For example, Atlanta has estimated that their trees have prevented the need for USD$883 million in storm water retention facilities as they will soak up water, slowly release, it and regulate hydrological infrastructure.

Philippe Clergeau: The political project is fed what it is provided with. Why shall we transition towards greening? Because there is a demand to this effect. I believe, everyone has realized how useful this was, in particular to mitigate the urban heat island effect. The IPBES (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services) report, published in May 2019, has successfully raised public awareness about loss of biodiversity. In cities, we will not protect wild boars, but we will favour squirrels and hedgehogs and further habitats. Keeping plane tree lines and sedum-covered roofs is monoculture. This will not help reduce our vulnerability toward climate and health hazards.

These aims seem fashionable at the moment, but they do not constitute a political project. If we head towards complexity – which, I believe is the opposite of politics, as, on the contrary, politics pursues simplistic goals –, we will then get a chance to reach functioning in the long-run. Although something may disappear, the rest will continue on living. Functioning food chains lead to reduced needs in watering, weeding, and fighting invasive species. I like the word “sustainability” because it contains a strong political project. We will be able to limit the management required by the presence of nature only by getting closer to ecological processes that have shown their evolution and sustainability. A complex system is a system in which management needs are reduced.

Michèle Larüe-Charlus: Political announcements are often schizophrenic. They always promise more greenery, but these promises are rarely followed through in practice for a number of reasons, the financial question being only one among many: network anarchy, the Green Spaces and Environment Departments’ reluctance to plant the streets and tall trees, the real phobia of falling leaves for some, everything competes to falsely green the streets with shrubs, trees in pots, hollyhocks alongside façades… However, the BM2050 project showed that the demand for trees, shade, and coolness in the streets of the city was the first request.

Yet this question goes beyond the mere political project; it encompasses an economic consideration. We realized that the trees that were planted in Bordeaux come from Northern Italy. Hence, we must now bolster the development of tree nurseries so that in ten to fifteen years, we are able to resort to operational short supply chains.

Singapore is very advanced in its naturalizing plan thanks to an integrated approach. What governance issues is France faced with when it comes to implementing biodiversity protection and nature in cities?

Philippe Clergeau: In France, the administration of local governments is managed by the Directeur Général des Services (DGS) – General Manager of Services. The DGS has the memory of the city and therefore holds a very central position. They sometimes are more important than the mayor. Still, they are in charge of allocating budget to all city hall services despite having superficial knowledge of them. The major issue about urban governance lies in its siloed functioning. This severely restricts any transversality. We were eventually able to gather all municipal services of Plaine Commune – an intercommunal structure, part of the Grand Paris; even the Youth and Sports department joined. Everyone was present because everyone had something to say: about the practice of public spaces that was going to be greened in a certain way, about what could block construction… There is certainly a governance issue in France! Paris has seven distinct levels of decision-making.

Michèle Larüe-Charlus: The DGS indeed holds a very central position. London plans to plant 50 million trees by 2050, so we decided to calculate how many trees we would be able to plant. The working group was composed of landscapers, planners, and engineers who know about Bordeaux. They estimated that planting 10,000 trees by 2050 would be legitimate. It would cost ten million euros. On this basis, it a question of political will but also of administrative will, and the DGS has an essential role in this regard.

Citizens ask for more green spaces; however, the presence of nature may not only bring pleasantness and health. Does it also bring negative externalities?

Philippe Clergeau: We actually try not to mention this. It is already quite difficult to explain how positive it is, so if we started talking about all of the negative aspects… We recently submitted a report to the ministry, which immediately abandoned it: if people are told that pollen allergies are going to continue developing because the weather is going to become warmer and air pollution is not going to decrease, or that more biodiversity also implies more mosquitoes… I am now trying to stop pond development in cities because we are not able to properly manage mosquitoes. A conservationist would propose we introduce frogs, but the city-dweller, who has the final say, would only be annoyed by croaks. Finally, I must mention the sanitary question, including illness and phobia, as well as the cleaning and removing of dead leaves, not to mention the cost that it produces. In other words, we will not be able to increase the introduction of biodiversity without public awareness, because spiders and pollinators are essential.

Lim Liang Jim: Broad acceptance is indeed a very important topic. If we want to live in harmony with nature and biodiversity, we must accept that there will be challenges we will face from time to time. We have been working on managing and mitigating human and wildlife interactions, but it is necessary to understand that, although we have enjoyed the fruits of our City in a Garden vision, there is a risk that trees might fall, that wasps will sting, etc. In 2019, we recorded high numbers of dengue fever. Perhaps due to climate change, unseasonably hot weather and heavy rains have caused the dengue mosquito to change its life cycle, presenting a permanent challenge. This is something we are working on, but public education must take it into account, so that people understand that nature is all-encompassing and there is a need to understand that there will be challenges along the way.

We will not be able to increase the introduction of biodiversity without public awareness.

– Philippe Clergeau

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Lisbon beyond the Tagus

Helsinki : Planning innovation and urban resilience

A warm tomorrow

Nature in the city

Breathless Metropolises

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.