Network together: How metropolises could reinvent attractiveness

Cities are magnetic, exerting their irresistible pull on people, ideas, and innovation alike. For a long time, these powers of attraction appeared the natural consequence of geographic advantages and political influence, economic vitality and cultural clout. As cities and specifically metropolises are increasingly competing on a national and international scale, attractiveness, a city’s ability to draw and retain resources and to stand out from its peers, has become for many cities a strategic goal of its own. To ensure attractiveness towards companies, visitors, and residents alike, cities are working to better understand and harness their potential, building on their specificities to create a recognizable brand through elaborate territorial marketing strategies,

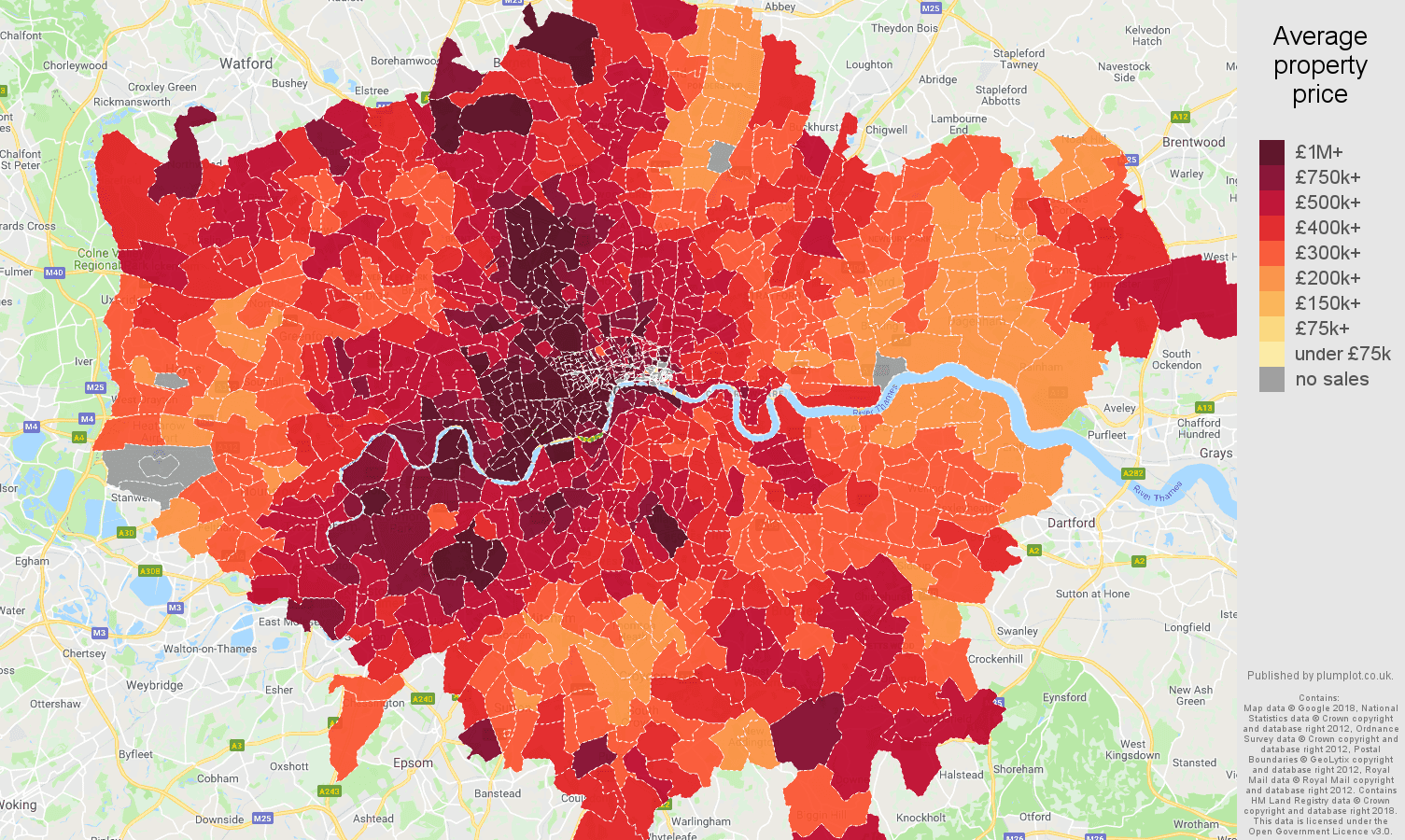

But attractiveness, notably of the touristic kind, also creates negative externalities, as evidenced by Venice’s, unenviable situation, but also by the difficulties encountered by Barcelona: A victim of its own popularity, the city saw its annual number of visitors soar from 1.7 million in 1990 to 7.4 million in 2012. This steep rise has caused the Catalonian city to become increasingly concerned with its ability to remain attractive… to its own population, strained by the pressure tourism exerts on real estate prices and public spaces.

A victim of its own popularity

Venice saw its annual number of visitors soar from 1.7 million in 1990 to 7.4 million in 2012.

But don’t be mistaken: at 12% of the city’s GDP, tourism is a precious source of revenue for Barcelona. It is the inequality generated by what she suspects is a tourism bubble that mayor Ada Colau now seeks to battle. From a cap on the number of tourists entering the city to a tax targeting short stays, the city has taken drastic steps to tackle rising rents and unauthorized rentals. This included dealing a stealthy blow to Airbnb, requiring that all apartments put up for rent on the platform obtain a permit, and imposing a €60,000 fine when it failed to comply.

With 7.8 million foreign tourists in 2014, Amsterdam is addressing a similar conundrum using a radically different tool. In 2013, the city launched “Stad in Balans”, an initiative aimed at achieving the delicate balance required to ensure sustained quality of life for residents while continuing to appeal to tourists. Measures include building 5,000 new housing units annually, combatting illegal hotels, and alleviating the most bottlenecked areas of the city. At the heart of this action is an effort to reconcile the –at times incompatible- rhythms and demands of locals and visitors.

Attractiveness is a subtle equation of which cities do not control all the variables.

The lesson arising from these two examples is clear: more than a strategy, attractiveness is a subtle equation, of which cities do not control all the variables. Another example of unexpected, and sometimes unwelcome urban attractiveness is the appeal some European cities exert on refugee populations, forcing them to implement a resilience strategy in the face of a demographic shock of unprecedented breadth. Additionally, other cities, eager to maintain their innovation potential and economic standing, are turning to selective attractiveness policies aimed at seducing young, qualified professionals through tailored housing, transport, and leisure policies. This choice necessarily implies an influx of lesser-qualified labor, showing once again how volatile the balance of attractiveness is, and how some of its parameters are beyond a city’s control.

One final thought: in this world of exchanges that is being built before our eyes, a city’s attractiveness might be more than its ability to concentrate resources and talents: it may well be its ability to connect the resources and talents of other cities within its network. The notion of attractiveness would then be enriched by the notion of influence, and attractiveness strategies could rely on cooperation between cities and the construction of networks rather than competition. Metropolises would take advantage of the synergies inherent to these networks to compensate for their competitive disadvantages, absorb negative externalities, and increase their influence. Driving urban attractiveness through a network strategy rather than a competitive approach: beyond the apparent paradox, a brand new field of innovation is emerging for metropolises.

This op-ed first appeared in Urban Snapshot (October 2016) by La Fabrique de la Cité.

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Helsinki : Planning innovation and urban resilience

Forget 5th Avenue

Long live urban density!

Toronto: How far can the city go?

German metropolises and the affordable housing crisis

Berlin Focus

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.