Psychoanalysis of the smart city

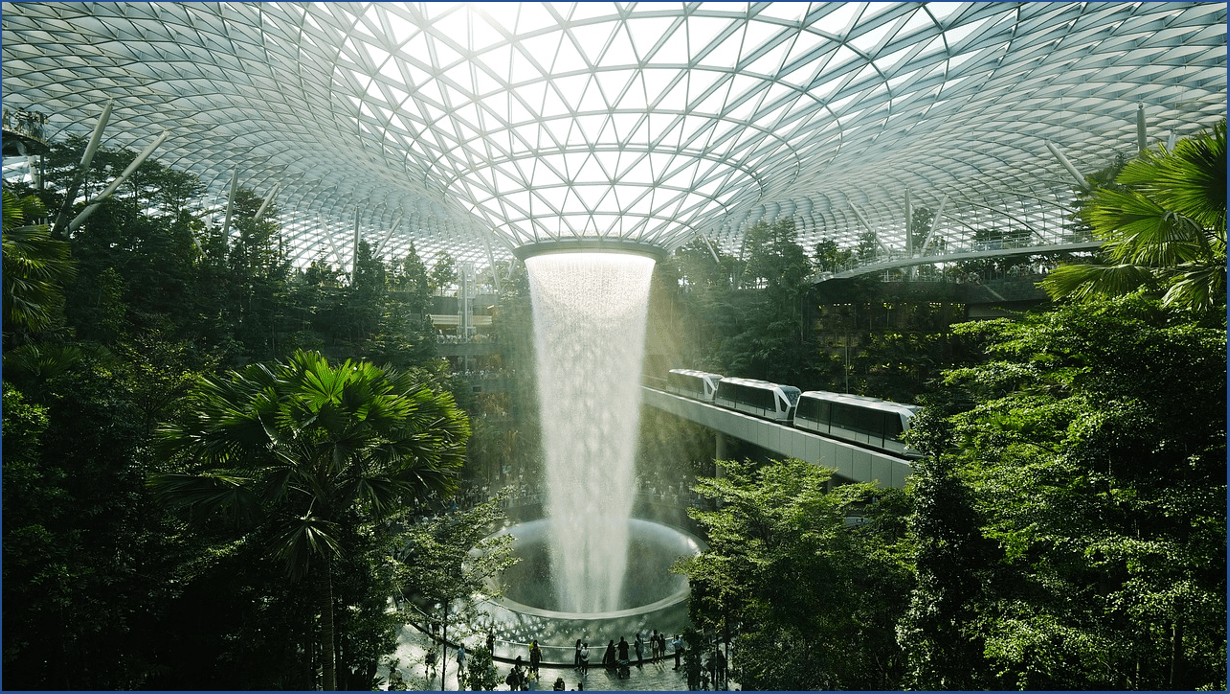

The emergence of data in cities has given rise to a federating narrative built around the term “smart city”, which appeared some fifteen years ago. This narrative was written with a multifaceted promise in mind: that of a city which would be more livable, more sustainable, more resilient, more efficient, more… etc. We all wanted to subscribe to this promise and have all fed on this vision of a future city disrupted by technology.

There is a long way from promises to reality. In fact, one may rightfully ask whether technology, in the way it is currently being applied to all things urban, far from being disruptive, is not in many ways eminently conservative.

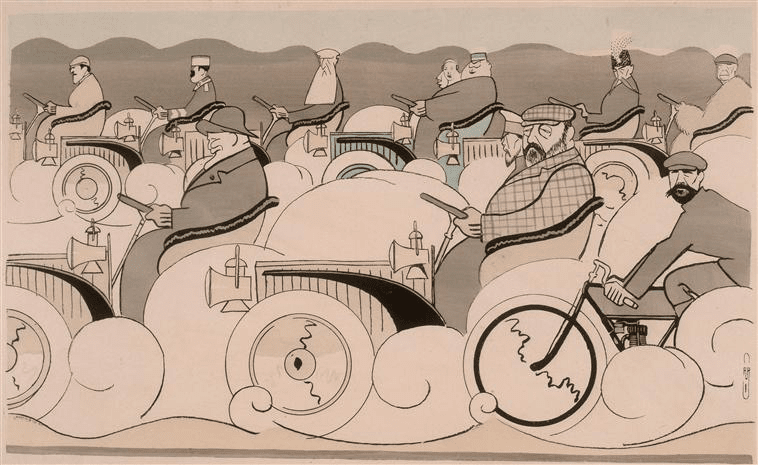

The example of urban congestion is striking: the “smart” approach was to solve this issue that is inherent to the very existence of cities; in reality, it has only worsened the problem. As shown by studies conducted in New York City or Boston, tech has added on new kinds of mobility which, far from filling up individual cars and combating solo-driving, have emptied out public transit and replaced active modes (cycling, walking). We venture a question: to what extent does tech in cities feed off the flaws and malfunctions of our urban systems? And when one feeds off a system, does one really have an interest in changing it?

Tech is also conservative with regard to environmental issues. Curiously, the narrative around the smart city has always posited that it would be sustainable. Such is not the case at all today. The physical infrastructure behind tech on the one hand, and the collection, processing, and storage of data on the other hand, require colossal, ever-increasing quantities of energy, as noted by the Shift Project. Tech uses more, much more energy than air transport, and the growth of its consumption is in the double digits. Data is often called the new oil: the fact is that we have interpreted this analogy literally and have adopted a very 20th century approach to tech in cities. Just as the economics of fossil fuel require ever more surveying, drilling, and commissioning, so we blissfully accept the claim that tech will require ever more data to function. This, in the name of the famous Moore “laws” which, far from laws, are mere conjectures. “The smart has captured the green,” Antoine Picon writes in La ville rêvée des philosophes, a book co-edited by La Fabrique de la Cité and Philosophie Magazine.

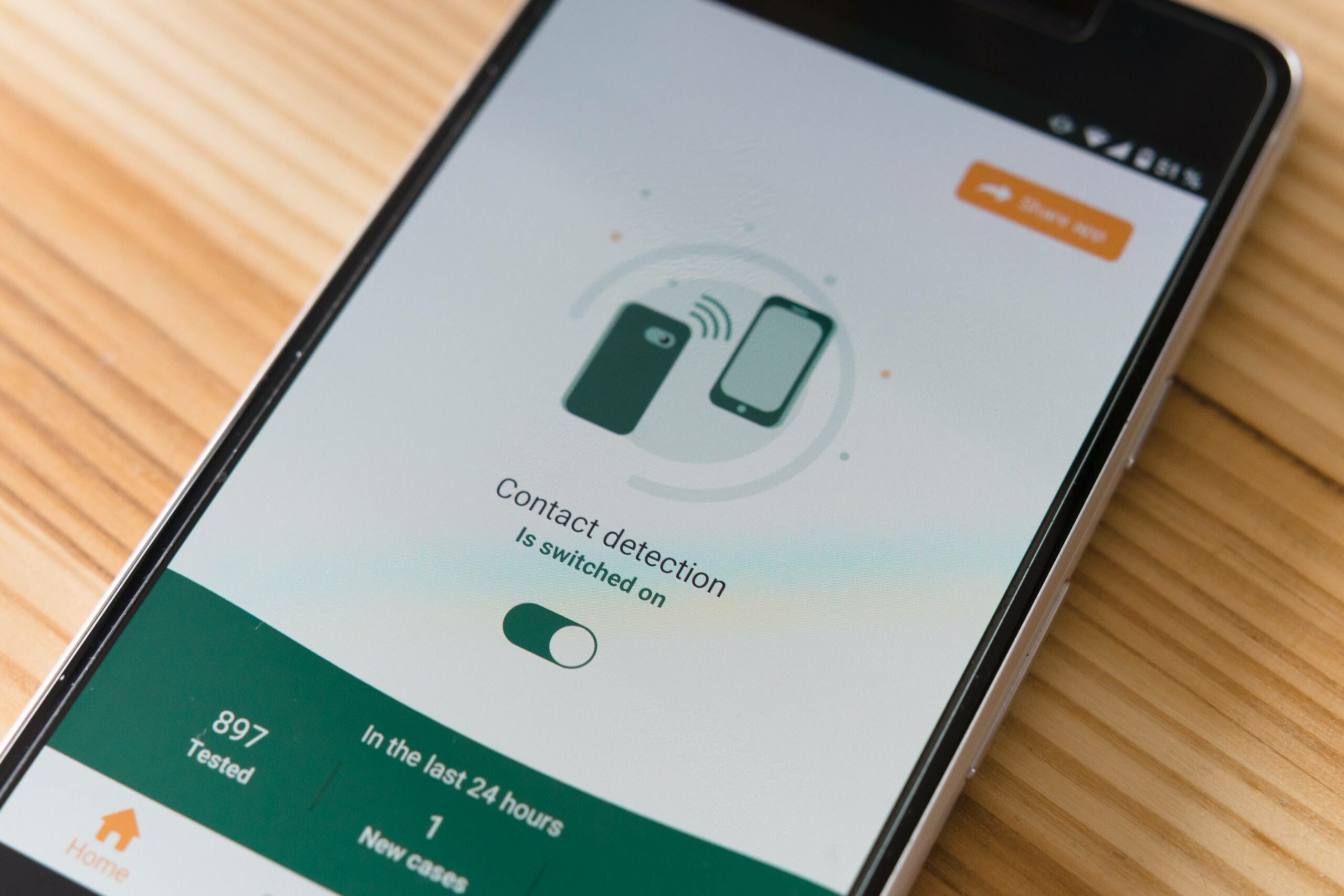

The ecology of technology has yet to be built, along with that of the smart city. Let us get on with it! Time has come to challenge technology, and particularly its urban applications, as our cities concentrate energy consumption and CO2 emissions: to overcome its addiction to “always more” (more well-being, inclusiveness; in short, more urbanity) using less data. Utopian? Not really! Firstly, the minimization of data collection has been at the heart of the personal data protection regime ever since its inception, and has since been picked up by the GDPR, which could become a soft law tool beyond EU borders, as evidenced by the strategies of certain international (notably, American) companies. Secondly, beyond the issue of personal data, research is currently being conducted in the field of artificial intelligence regarding data minimization, which shows the interest of this approach both from an economic and security standpoint.

To become more urban, tech must work on its addictions. And so must we. We have tried to make tech a product meant to simplify cities, when the goal should have been to make it an ally, an indispensable tool at the service of an indispensable and rich urban complexity. The ultimate justification of the smart is not to always do more. It is to ensure that we can move around in our daily lives without degrading our environment in Los Angeles, Paris, Beijing or Bogota; it is to ensure access to drinkable water in Indian cities, to put an end to urban sprawl in Western countries, and to promote sustainable electrification of the African megacities that are growing before our eyes.

Psychoanalysis of the smart city [In French]

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Behind the words: urban congestion

Toronto: How far can the city go?

The political and technological challenges of future mobilities

Viktor Mayer-Schönberger: what role does big data play in cities?

Thomas Madreiter: Vienna and the smart city

“Once Upon a Time”…

Boston Focus

Data for urban citizens

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.