Singapore, a city-state “compelled to power”: Étienne Achille’s viewpoint

From 10 to 12 July 2019, La Fabrique de la Cité brought a delegation of thirty experts and practitioners of urban development to discover Singapore, a proactive and unique city-state, reputed for its pioneering policies in the fields of housing, mobility and the smart city. Étienne Achille, Inspector General at the French Ministry for Agriculture and member of La Fabrique de la Cité’s Steering Committee, took part in this urban expedition. After considering Singapore’s unique identity and limited geographical situation, he shares his take on the challenges of a complex and fascinating urban model.

Identity

Temasek: place surrounded by water

Singa Pura: the lion city (or more correctly, the tiger city).

The successive names given to Singapore are the foundation of its dual identity:

- the relationship between land and sea, as demonstrated by the symbolic Merlion, a contemporary face of the island;

- the presence of nature and wildlife/an urban embryo.

These names reveal an original deep blending, as one comes from Javanese and the other from Sanskrit, linking Singapore to South-East Asia and to the cultural area of the Indian sub-continent.

With an identity built on these foundations, the city-state has an approach and narrative that are meticulously constructed.

Peter Ho (Senior Advisor, Centre for Strategic Futures) highlights this primary attribute of Singapore: a city-state. It compares its status to that of Athens or Venice. This voluntarism may bring a smile, but it reveals an explicit intention to root the city-state in a long period of time, to create a historical context in order to establish the fact that its financial and trade power has a global reach that can serve as a model.

Singapore naturally has the characteristics of a city-state, but it is more in the contemporary category which includes, for example, Brunei, the United Arab Emirates, Hong Kong (without sovereignty), Kuwait or Qatar:

- limited size;

- considerably man-made territory;

- limited natural resources with the exception of oil;

- power monopolised by a family, clan or system;

- assertion of identity and sovereignty;

- intense promotion policy (appeal for investments, tourist destination);

- global competition for the status of “a modern principality”;

- position as a regional and even global financial and port platform;

- sensitive relations with neighbouring states;

- strict controls on immigration, particularly on migrant workers, through a quota policy;

- strong ethnic challenges, etc.

Ethnicity is a key issue on the island. As symbolised in the national flag, Singapore is three quarters Chinese, but at the centre of Malay territory. Specific and yet Chinese, as demonstrated by the ruling power since 1965. Singapore collates demographic statistics according to origin which are used as reference points for many public policies, in particular for housing. The government determines ethnic composition when allocating programmes funded through its Housing and Development Board.

Sovereignty

Three figures leave no room for ambiguity with regard to Singapore’s state sovereignty:

- One third of the state budget is allocated to defence;

- Two of the four natural reserves on the island are military territory;

- The state controls 75% of land.

Land is therefore a question of national sovereignty in Singapore, and is managed and promoted by the government through different kinds of leases which vary in duration according to the type of development. A 99-year lease is the main home “ownership” tool for housing units constructed by the Housing and Development Board. However, in a country that has been established for less than sixty years, the future of this type of lease creates uncertainty with regard to an entire and vital area of government action in its relations with citizens, particularly as the state has turned public housing into a “market”.

Through housing, questions are being raised as to what this key component of state sovereignty will become in a few decades. Yet this timeframe is the exact amortisation period of housing units and of many current and future investments.

Power

Singapore seems to be compelled to power. It is also compelled to provide a narrative of power, as it controls its complex relations with neighbouring state Malaysia and as it upholds the vital movement which has been producing its exceptional development for the last fifty years. “Majulah Singapura” – “Onward, Singapore” is the national motto.

This forced march takes root from childhood in a highly competitive and strict education system which aims for excellence (cf. the tradition of caning).

In the city, or rather in the city-state, urban development has also been imprinted from the outset with this forced march[1]. While procedures include consultation, they are aimed predominantly at building[2], at completing the projects designed by the planning authority, which itself is restricted by a policy to renew housing regularly and the constant development of the supply of retail and office spaces.

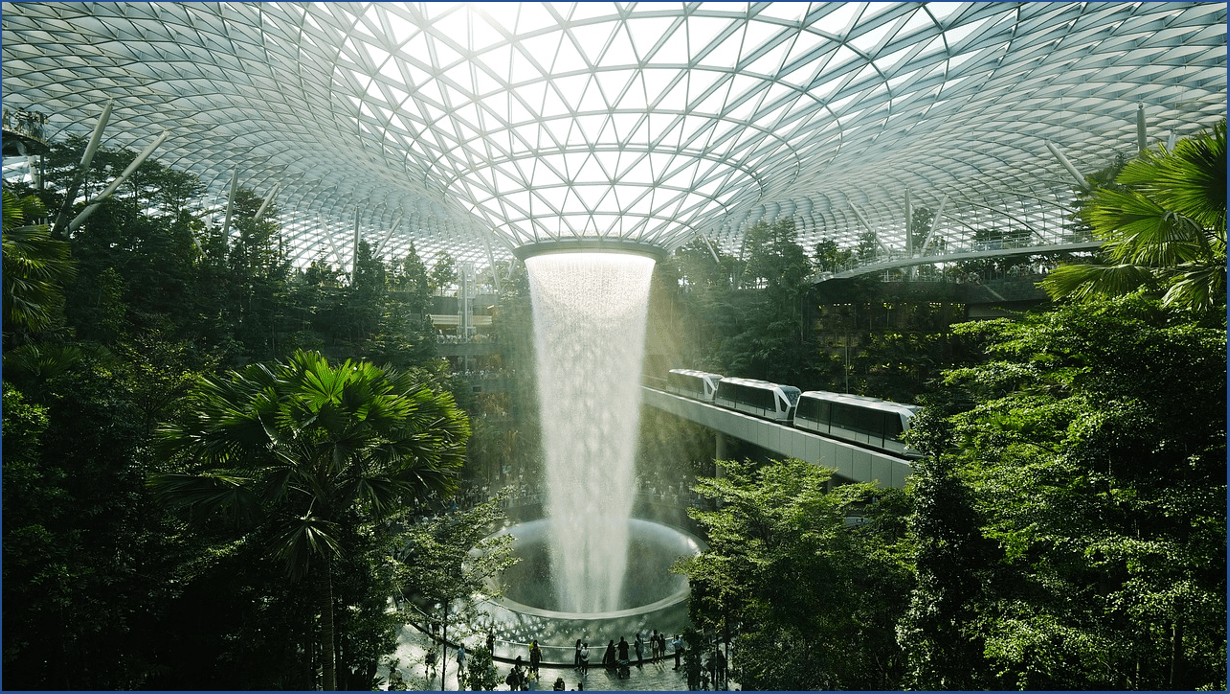

This forced march can be seen in particular in retail property, which structures both the city centre (Orchard Road in particular) and the outskirts (the new Jewel concept at Changi Airport).

However, in the last two years, the race for retail space has come up against a drop in sales (-18% in 2018 compared to 2017) and in rents and a rising vacancy rate (+7% over the third quarter of 2018)[3].

This situation is the combined result of a saturation of supply (75,000 sq.m of new space to be completed in 2019-2020), increasing competition for e-commerce, in which Singapore is surprisingly lagging behind, and the obsolescence of many shopping malls.

It forces owners to make significant investments in renovation to adapt spaces to the expectations of a clientele[4] which is becoming more reliant on digital technology and aspires to renew ties with nature, omnipresent in the official line. The profitability of projects is affected by this, which is a sign that the model may have reached its limit.

Elements

- Earth

– Land

Singapore’s surface area has increased by 25% in fifty years (from 578 square kilometres in 1965 to 721.5 square kilometres in 2019) through the land reclamation policy and the levelling of hills. The two key infrastructure elements – Changi Airport and the port – have also reclaimed land from the sea to enable Singapore to play its role as a global trade platform.

With a limited territory, the 63 islands of the Singaporean archipelago are a precious source of land. They have become “utilities”, specialised by major urban services roles:

– Underground

This is the new frontier for land development. Singapore sets out its strategic activities underground:

- storage of fuel and ammunition for defence;

- wastewater treatment and desalination plants;

- cold production plants (particularly the largest in the world under Marina Bay Sands);

- transportation (road, underground trains);

- container tunnels in the port area;

- power grids installed at more than 100 metres below the surface.

– Aboveground

As it lacks agricultural land, Singapore encourages the development of urban agriculture (see the Sky Greens vertical farm project) and the technological innovation that makes it possible. The Garden City mega-project demonstrates the extent to which the island is willing to consolidate its supply. Exporting this expertise in South-East Asia shows just how much Singapore intends to extend its reach.

– Outside the territory

The island’s physical limits are exceeded by Singapore’s expansion outside of its territory. The strong arm of property outside of Singapore, the GIC sovereign wealth fund (estimated at US$300 billion) is invested primarily in retail, office and hotel real estate in major global cities in which profitability meets its management targets.

Singapore’s influence also extends outside the territory, both through the expatriation of 215,000 of its citizens and the policy to host foreign students. However, the 2008 crisis curbed the latter; and furthermore the government decided to limit the number of foreign students in the “Asian Boston” from 2011[5] in response to growing public unrest expressing concern about the increasingly few places for Singaporean students. This restriction of unbridled expansion reflects the state’s dilemma to maintain intensive development in line with the interests of its own population.

- Water

The paradox in Singapore is that it records 2,400 millimetres of rainfall each year and has 8,000 km of waterways (compared to 3,495 km of roads), and yet it is unable to store all of this clearly strategic resource. Singapore has met this challenge by creating four sources of supply, its “four national taps”:

- water from local catchment areas: these have increased from half to two thirds of the island’s total surface area since 2011 and 17 reservoirs are used for storage;

- imports from Malaysia: drawn from the Johor River, this may account for a maximum of 60% of daily needs, according to the terms of the 1962-2061 agreement with Malaysia;

- NEWater: from the growing recycling of used water, it covers up to 30% of current requirements;

- desalinated water: launched in 2005, it can cover up to 25% of needs[6].

The latter two sources will cover 80% of demand in 2060. This mix of solutions represents a departure from the recurrent crises that lasted until the 1970s. Since then, the state has invested in infrastructure and innovation to ease the constraints.

Generation “Sam”

Sam is a young Singaporean researcher aged around thirty. After studying abroad, he decides to return to Singapore to work, particularly due to the highly favourable tax system in force. However, his country’s political and development model seems to be increasingly at odds with the expectations of his generation, which is highly educated, connected to the world and has often spent time abroad, and which sees the current regime as a relic of the independence era that is not suited to current and future social, environmental and political conditions. This individual vision cannot be applied to all young people of course. However, it does shed light on the question regarding the future of the city-state’s political system after two generations of intensive development in a regime of “démocrature”[7]. Sam is a “millennial”, probably descending from those in the Singaporean movement, but he does not feel that this past should structure his future which he hopes will be open and free and will fully encompass environmental issues.

This youthful vision of the future raises the key question of demographics in Singapore.

The island has a population of 5.8 million, including:

- 47 million Singaporean citizens (2.64 million Chinese, 519,000 Malays, 258,800 Indians and 52,000 from other ethnic groups);

- 37 million skilled foreign workers (= expatriates), i.e. almost half of the number of Singaporean citizens, which highlights the great dependence on this population which is key to Singapore’s performance.

Singapore also has 183,700 millionaires[8], a figure which echoes the 250,000 “foreign domestic workers” or helpers, mainly from Indonesia and the Philippines.

120,000 people commute from Malaysia.

These figures are given against a backdrop of an ageing population,[9] resigned to seeing the established system prevail as long as there is economic growth and a constant standard of living, which, given the statistics, will only be possible through increased immigration. This situation is already causing tension, particularly on the labour market: by reducing the quotas in 2018, the government sparked protests in a number of business sectors, starting with hotels and restaurants, a significant component of the key tourist industry.

Sustainable Singapore?

Demographics, political regime, resources: there are many key questions regarding the sustainability of Singapore’s model.

Questions are raised regarding the pursuit of intensive development:

- S$1.7 billion to build Jewel, the new “destination” in Changi Airport. Its concept is eloquent: a shopping and leisure centre over 135,700 sq.m designed[10] as a “destination” which reproduces a rain forest at a latitude where the average temperature is 25°C, i.e. the temperature of the air conditioning for visitors/customers of the site. Visitors are either air passengers (40%) or inhabitants of Singapore (60%). Jewel strives to become the ultimate leisure and shopping experience;

- the extension of the Central Business District on land freed up by the conversion of part of the port terminal, itself relocated to new reclaimed land.

These two examples round off the contrasting profile of “Green Singapore”, as presented by officials. In practice, it is more of an attempt – albeit a brilliant one – to reduce environmental threats and optimise the limited resources inherent to all city-states, rather than a real low-carbon transition policy, which is almost impossible to achieve given the current energy mix.

In practice:

- in terms of vehicle traffic, Singapore is rolling out a new toll system using artificial intelligence to optimise control over the use of cars in the urban environment. However, the reduction of traffic does not appear to be an explicit goal;

- the heavy reliance on fossil fuels does not appear to be offset by a renewable energy strategy commensurate with the challenges faced, while the geographical location seems to be favourable for wind and solar power in particular;

- even the single-minded pursuit of greening the island (green areas have increased from 37% to 47% of the territory since 2000) seems more to do with a form of “Nature naturata”[11] than a genuine weapon in the fight against climate change.

Overview

From the two-day urban expedition around Singapore emerged the image of a city-state which overhangs, sure of its power, or at least asserting it, rightly proud of what it has accomplished in half a century.

Singapore’s development is vertical as a necessity dictated by its territory. The elevated position is naturally promoted there in the many urban and even natural spaces on this level.

The Skywalk which connects the 50th floors of the seven towers of the new Pinnacle@Duxton housing complex (in the Tanjong Pagar district), the famous terrace of the Marina Bay Sands, the many downtown rooftops, the treetop walk at the Gardens by the Bay, the Southern Ridges canopy walk spanning kilometres (with the Henderson Waves), the suspended bridges in the jungle near the MacRitchie Reservoir, all these places afford a view from above of the success of a limited territory which has been enhanced.

In addition to its welcome purpose of creating breathability in the dense city, this overhang also features in Singapore’s official narrative, championed by Peter Ho, of total control of urban development: overall strategy/15-year master planning, 5-year concept planning/resident consultations (an embryo of democratic debate) / operational implementation and supervision of projects.

This height is also seen in pride, this elevated idea that Singapore has of itself, including in the political attitude towards its neighbours, Malaysia in particular.

This elevated and upward-looking vision remains, more than half a century on, a legacy which is still hardy but increasingly questioned with regard to Lee Kuan Yew’s original ambition.

[1] “Urban renewal means no less than the general demolition of virtually the whole 1,500 acres of the old city and its replacement by an integrated modern city center worthy of Singapore’s future role as the New York of Malaysia” (government declaration for the launch of its urban renewal programme, 1966).

[2] “Build narrative. Build democracy. Build Infrastructure.” – presentation by Antoine Picon during the La Fabrique de la Cité urban expedition to Singapore, 10-12 July 2019.

[3] Data from the Urban Redevelopment Authority quoted by Bloomberg News.

[4] In response to this drop in visitors, the commercial centre of downtown, Orchard Road, has completely overhauled its concept to include a farmers’ market, places for cultural expression, considerable greening and the scenography of the street itself. Source: Reimagining Orchard Road, Centre for Liveable Cities Research, September 2017.

[5] The number of foreign students has fallen from 95,000 in 2008 to around 75,000 since 2015.

[6] Source: Singapore’s national water agency, PUB.

[7] V. Démocrature : comment les médias transforment la démocratie, Gérard MERMET, 1987 (in French).

[8] Credit Suisse Research Institute’s 2018 Global Wealth Report.

[9] In Singapore the number of inhabitants aged between 20 and 65 for an inhabitant aged 65 and over increased from 7.4 in 2010 to 4.5 in 2019. The national fertility rate is 1.16, but only 1.09 in the Chinese majority (76%) of the population.

[10] Safdie Architects. The practice also designed the Marina Bay Sands complex, the iconic building which acts as Singapore’s global image.

[11] V. Ethics, SPINOZA, quoted by Raphaël LANGUILLON during the urban expedition.

Étienne Achille is Inspector-General at the French Ministry of Agriculture. A graduate of SciencesPo Paris and holder of a post-graduate degree in Anglo-American studies from the University Paris IV-Sorbonne and former pupil of the École nationale d’administration, he began his career in 1990 between Paris and Brussels as Head of the European Affairs Office of the Ministry of Agriculture, where he took part in the first reform of the CAP. He moved into the corporate world in 1992 as Head of External Relations at Euro Disney to facilitate among public stakeholders the development of the leading European tourist destination and the creation of the Val d’Europe urban centre. From 1997, he was deputy secretary-general of the national mission chaired by Jean-Jacques Aillagon to produce the public cultural event to celebrate the new millennium in France, in partnership with major regional cities. In 2001, he joined the Ile-de-France Regional Council as Head of Housing, Culture and Solidarity and coordinated the development of these new public policies. Following the decentralisation process, he was appointed deputy director general of services in 2005 to create and manage the “Society” division, in charge in particular of housing and urban policy, health and social training, culture, sport and tourism. In 2016, he became director general of services at the new research university Paris Sciences & Lettres, then advisor to its chair’s office. He was appointed Inspector General of agriculture in 2018; within the Council on food, agriculture and rural areas (CGAAER), where he manages intelligence on the digital transformation in the sector and conducts assessment and advisory assignments.

Étienne Achille is a member of La Fabrique de la Cité’s Steering Committee.

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.