Spatial justice, managing the situation to enable development?

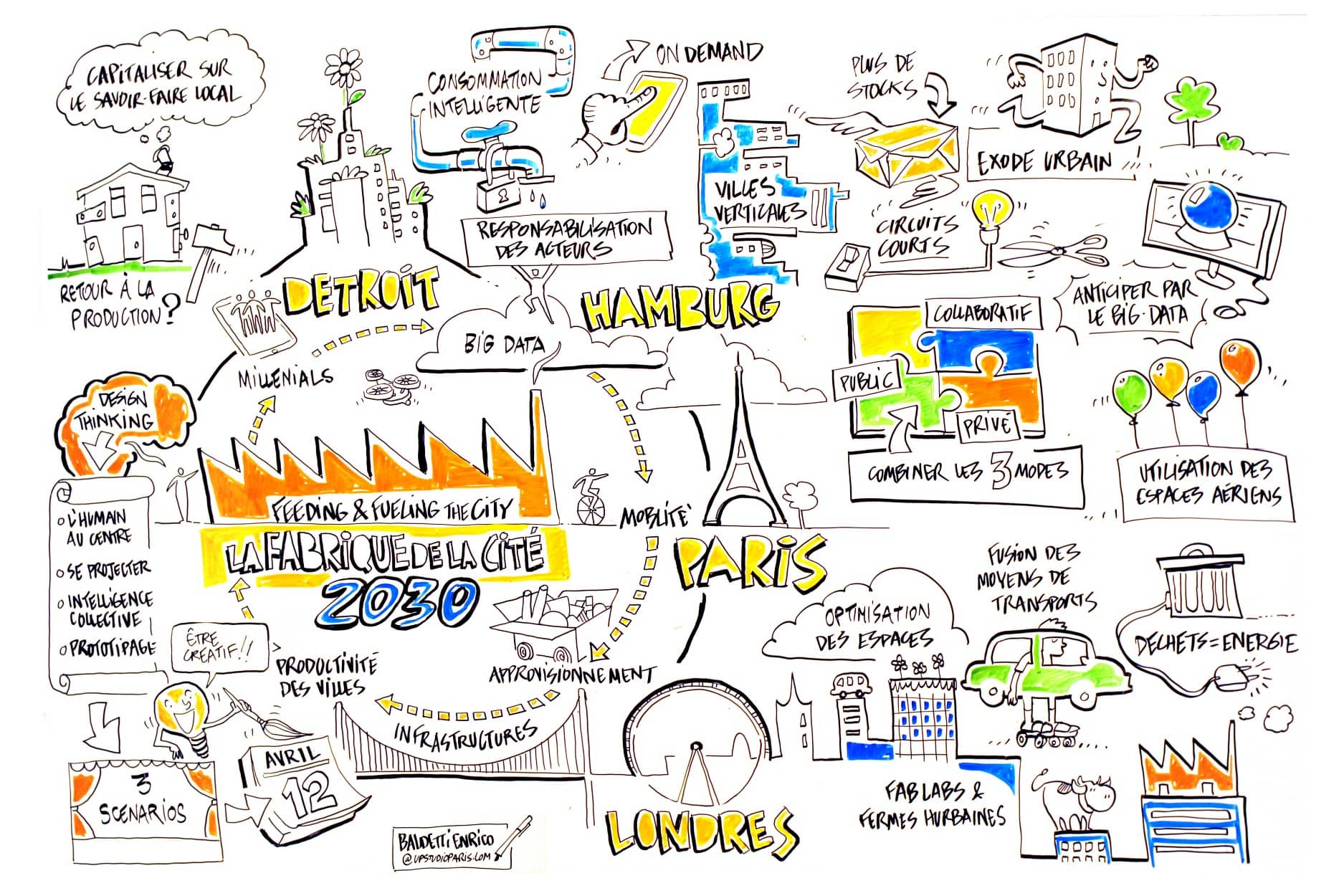

How can the concept of spatial justice be redefined at a time when metropolisation stems from the globalisation of spatial organisation factors? Which geographies are emerging from the yellow vest crisis? Michèle Larüe-Charlus, head of the #BM2050 mission at Bordeaux Métropole, Jacques Lévy, professor of geography and urban planning at the University of Reims and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL), Cyril Roger-Lacan, co-founder and CEO of Tilia, and Pierre Veltz, winner of the 2017 Grand Prix de l’Urbanisme, bring their insight on these questions. An opportunity to analyse the current crises across our local areas and to redefine the terms of the debate in the framework of a new area of study, introduced in January 2019 during the debate “Faced with the current crises, act for tomorrow” held at Leonard:Paris : “Territories and metropolises”.

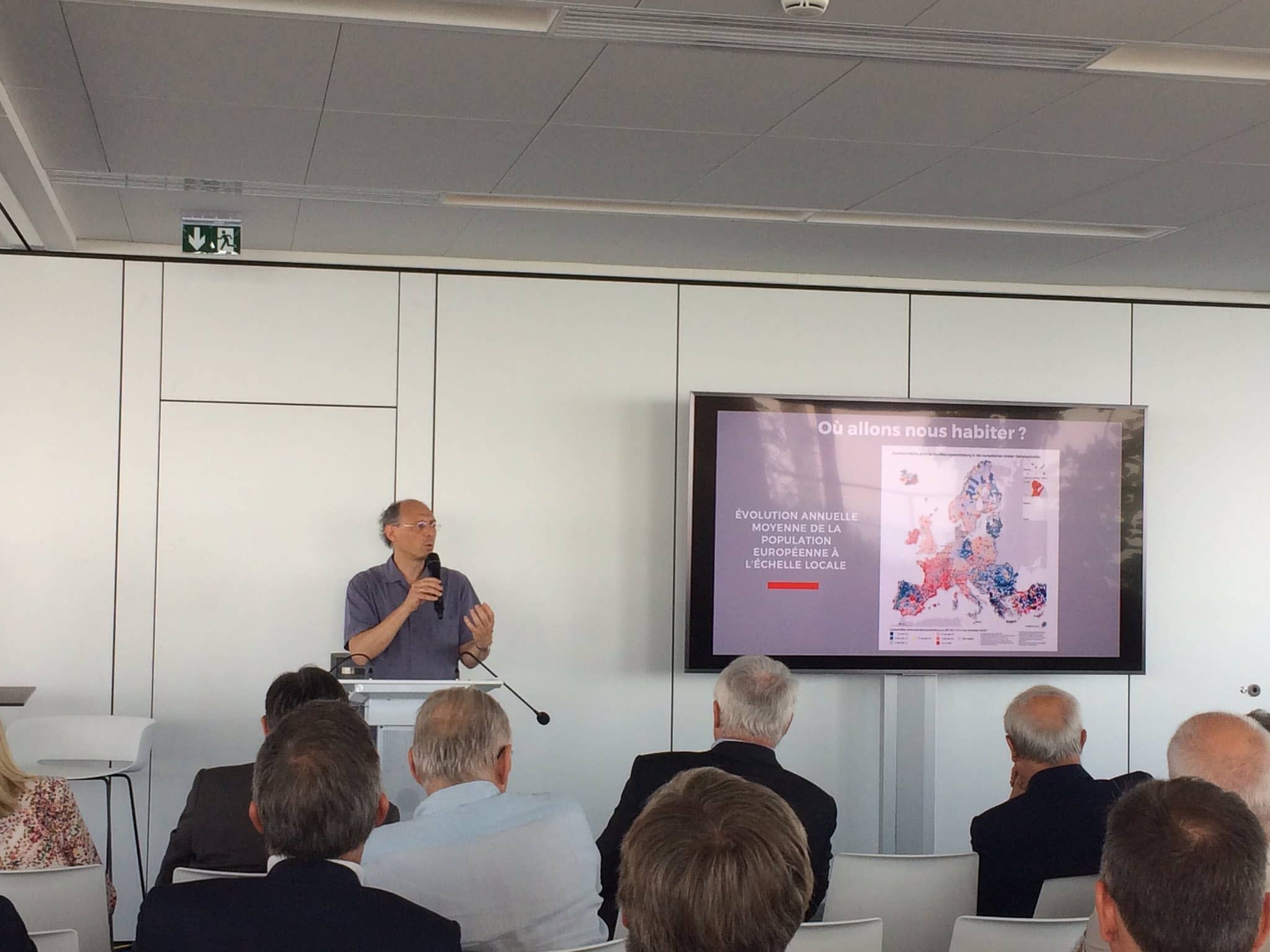

Which geographies are emerging from the current crises?

Pierre Veltz: The effect of globalisation, in France and in other developed nations, has been to give metropolises greater weighting. In particular, there has been a very high concentration of employment – skilled jobs above all – at the centre of metropolises. This does not allow us to claim, however, as Christophe Guilluy has, that there is a divide between healthy cities and peripheral areas in France. In reality, the situation is more complex. Admittedly, major cities have benefitted from globalisation but they have also seen inequalities increase very sharply. If you look at the median incomes, contrary to what one may think, there is a certain levelling between low-density non-metropolitan areas and metropolitan areas. There is of course a major axis of demographic and economic decline which runs from the Ardennes to the Massif Central region. In this diagonal void, according to the latest data from the French statistical institute (INSEE), the situation is worsening. However, in other areas, there is a very surprising patchwork. In relative terms, a certain number of small and medium-sized towns such as Figeac, Vitré and Laval, regardless of whether they are directly under metropolitan influence, are enjoying economic dynamism that is not the case in other areas. This is why I prefer the terms “dense” and “low-density” areas to “metropolitan” and “peripheral” areas because this terminology allows us to consider the interrelations much more than the oppositions: many low-density areas are under metropolitan influence. I believe that the main divide today, reflected in the current protests, is cultural in nature, with population groups that are failing to communicate because they no longer live in the same environment. In that respect, the static inequalities in income or cultural resources may be secondary to the ability to plan for the future.

Jacques Lévy: Representations are also part of actual geography. If we compare electoral maps with areas of yellow vest activity, a political geography emerges. There are two political realities in France but they are not necessarily the political concepts that are presented. I also agree with Pierre Veltz that suburban areas are parts of metropolises. They are a concept invented by the INSEE to take into account new forms of urban development in urban areas, morphologically detached but functionally connected. Suburban areas include municipalities which send more than 40% of their active working population to the rest of the urban area.

I like to make a distinction between urban and rural on one hand, and towns and countryside on the other. Today, the term “urban” encompasses towns and countryside. To which category should suburban areas belong? In the countryside, naturally, but not in a rural area because there is no longer a rural society in France structured by land. There is also what the INSEE calls isolated municipalities, which make up 4% of the population, send few workers to urban areas and have lower poverty rates than major agglomerations. This does not explain why some of the more well-off inhabitants of suburban areas see themselves as deprived: there is no correspondence between productive spaces, living spaces and the spaces of political discourse. This explains just how complex geography is.

Michèle Larüe-Charlus: I agree with Pierre Veltz: this is not an economic issue but a cultural one. There has always been a clash between the mayors of towns and of rural communities, with the latter considering themselves the spokespeople of lifestyles and socio-professional categories unfamiliar to city-dwellers. However, there are as many disadvantaged people in cities as in suburban areas but city-dwellers naturally have a different future to those in the periphery because they benefit from a stimulating environment. In Bordeaux, the number of executives has doubled, while employees in face-to-face sectors such as tourism have left to live elsewhere. To this we must add the inhabitants of the hinterland – labourers, farmers, craftspersons and self-employed professionals – who do not wish to live in the city. These last two categories make up the majority of the yellow vest movement. Unfortunately, despite an effort to make 40% of our property operations into social housing, we have very little power over their allocation, which rarely benefits the lower middle class – working poor, craftspersons, etc. On the day when, in Bordeaux, the intangible value of the hinterland equals the value of property in the historic centre, we will have achieved territorial equity. In the meantime, Bordeaux has undergone a very swift transformation and this crisis has just reminded us of this fact.

How has the mobility revolution reshaped France?

Jacques Lévy: We live in a society which gives some degree of choice, in a complex blend of constraint and freedom. The development of mobility with private cars made it possible to arbitrate either in favour of housing or in favour of mobility. Careful consideration shows that the share of income devoted to housing/mobility is the same in the city as in the suburbs: what is lost in property is gained in mobility and the opposite is true. It is a relatively neutral economic choice. This is why spatial justice cannot be considered solely based on a redistributive approach, ignoring this aspect of individual choice. This ability to make an individual choice also favours a “club” approach: those who live in the suburbs can choose their neighbours, while those who live in city centres cannot. These are two very different ways of life.

The yellow vests crisis is based on grievances regarding mobility. These are political demands. I believe that ultimately, it is in a motorist’s DNA to be libertarian. Any obstacle to this right to mobility, whether by tolls, taxes or speed cameras, is contested. Going beyond this right to mobility, the very idea of taxation is called into question. The major debate is interesting as there is an exchange of different points of view; the demands of the Yellow Vests have to include the reasons of other people, with, implicitly, this question: why would spatial justice imply that my demands are more important than those of others?

Pierre Veltz: I do not entirely agree with Jacques Lévy. Arbitration is not conducted in the same way for housing and transportation as there are major constraints upon the choice of housing. Of course, there is an original choice, for example, that of the dream of a detached family house… However, if this choice is to become reality, a mortgage must be granted or a tenancy agreement accepted. In addition, those who choose to live in suburban areas have to pay mobility costs that they had not necessarily anticipated. This yellow vest revolt is multi-faceted. Behind the political or libertarian choices regarding mobility, there are also very complicated economic situations.

The problem is above all to do with the suburbanisation model rolled out in France: the same situation does not exist in Germany! Once again, we come back to the question of governance and power of mayors in the urban development of their municipalities. This suburbanisation corresponds to a lifestyle that is for the most part based on an increasing number of residential housing estates which, as Éric Charmes says, become clubs. The outcome is a municipal map that is totally broken up, with a decorrelation between housing sites and local services. The main journeys are not related to commutes to work but to improbable routes that people, especially mothers, have to travel to access services (supermarkets, after-school activities, etc.).

Cyril Roger-Lacan: We often talk about the de-industrialisation of our country, but much less about the industrialisation of our lifestyles, whereas this concerns us all, whether we live in cities or in suburban areas. This industrialisation has significantly eroded collective living standards, particularly in suburban areas, with a type of industrial populism, a notion that Bernard Stiegler likes to use. I believe that the current crisis stems from this peculiar lifestyle that we have all been pushed into.

Which solutions can local stakeholders propose to combat spatial segregation?

Cyril Roger-Lacan: The environmental transition offers an interesting perspective: by creating an economic and social fabric in local areas which sometimes were lacking this, a new dynamic can be triggered, which can be a means of cohabitation, activities and skills for the energy transition. This is a new prospect: unlike the contemporary vision of industry, this is not about creating an activity that does not exist elsewhere or in which one area is better than another, according to a competitive and differentiating approach. On the contrary, the idea is to create what can be created everywhere, based on an approach of local areas’ resilience and ubiquitous development. Under these conditions, the environmental transition is an opportunity to overcome the social divide. However, fluctuating between the drive to achieve the environmental transition and a strong and often poorly managed centralisation, France is struggling to view it in this way. We continue to talk about the cost of the transition, when in Germany, Sweden, Denmark and Austria, they are talking about the opportunities to generate wealth.

Pierre Veltz: Today, start-ups are reinventing economic models aimed at urban areas alone, with projects that are very interesting but far from highly strategic. Yet the need for creativity and new models does exist: let’s just think about the reorganisation of transportation in suburban areas or the digital transition, which is so very necessary but which is frightening the industrial SMEs in our peripheries. Major breakthroughs would be possible if these worlds could come together. As Cyril said, I believe that we will have made progress the day that we see local areas as potential sources of new types of growth. The energy transition plays a key role in this, by creating new forms of cooperation and reciprocity between areas through energy co-generation. When that happens, it will no longer be a case of “metropolises against the others” but “metropolises with the others”.

Michèle Larüe-Charlus: We do need cooperation. Bordeaux has forged ties with four nearby towns, Libourne, Angoulême, Marmande and Saintes, with a view to achieving bilateral development based on local resources. Faced with the saturation of its urban logistical infrastructures, the metropolitan area has decided to take part in financing a logistics site in Libourne. With Angoulême, it has set up a business and property plan with a single developer for the joint development of the districts surrounding the stations in our two cities, while with Marmande, it has designed a reverse food logistics service. With Saintes, it has developed cooperation in the cultural sector.

How can the time and framework for action be defined together?

Jacques Lévy: “You have to take the time to go fast” was the slogan of the French national railway company SNCF. I believe that we must refuse the diktat of urgency and use the current crises to develop what I call an “interactive democracy”, which would work in conjunction with the representative democracy and allow society to be constantly involved. Yet this interactive democracy must be launched at a very early stage, when the challenges are defined. This change occurred in urban planning when consultation was invented. The decision used to be made by the mayor, who used his/her communications skills in the hope that the election result would be positive. Today, the most successful urban planning operations are based on proposals being considered collectively from a very early stage: values, guidelines, timeframes are discussed so that something can be jointly produced that will be the project itself, its completion and its assessment. This is what happened in Stuttgart with the Stuttgart 21 station project which was very interesting: after starting off on the wrong footing, they went back to the drawing board. A referendum was held to create a more serene atmosphere and the plan for an underground station which was previously opposed was ultimately approved. We must not be afraid of interactive democracy, of asking difficult questions and making citizens into decision-makers. We must not be frightened of expressing trust either. When asked “What do you want for society?”, citizens do not answer according to their own interests. They want a fair society and have extremely sophisticated ideas.

Michèle Larüe-Charlus: Bordeaux Métropole is conducting a participative democracy campaign along these lines: #BM2050. We devoted the first quarter of this approach to an anthropological-style consultation process, with a “camion du futur” van which went out to meet citizens and collect their ideas and impressions. We also held conferences and a serious game. The mayors of the municipalities in the metropolitan area also took part in organising their own consultation procedures. We have estimated the outreach of this initiative at 50,000 people. We have learned many lessons. One of which is that there is a certain schizophrenia in demands, with the desire to live in a low-density area in a house with a garden, while having access to a tramline. To come back to the issue of mobility constraints, we learned that our citizens believe in an upcoming revolution in working methods with the development of teleworking. In the coming months, our task will therefore be to launch a reforming policy and to find a governance method which meets citizens’ needs.

As regards the timescale, I think that we have to rehabilitate short timescales. In Bordeaux, our catchphrase is: “voir loin, viser court” (look in the long term, aim for the short term). It is a balancing act between these two timescales. As part of #BM2050, we are not asking ourselves what we are going to do in 2050. We are looking at how to act today, how can we have an effect on the current political decisions for a brighter future. One factor must be added to this: more policies and less administration.

Cyril Roger-Lacan: When we try to make real changes, you have to combine a long-term view with shorter-term timeframes. Ironically, I also think that we must learn how to rehabilitate the short-term. It is not only elected representatives who want to take action within the timeframe of a term of office. People want to see the results of their work. To build efficiently, we must leave the stakeholders to work on these issues in a representative democracy that can be enhanced by other formats. This is why it is important to take action on a local level and allow citizens to redefine and take ownership of their environment. Citizen commitment is not an abstraction or an ideological postulate. It is a reality. This is the result of open and effective urban planning, of a local political project. Citizens and major organisations are beginning to understand this. They adjust accordingly and take their place in these projects. I do not believe that we should oppose this democracy that I am not afraid to call “community-based” and the effectiveness of the work process. Efficiency comes from democracy. However, the question of State control is raised, when the result is many plans and little action…

Pierre Veltz: Management leads to development, a kind of development that is intelligent and astute. We talk a lot about participative democracy but we must first democratise representative democracy! It will be complicated as we do not have real local and agglomeration powers that are legitimate and identified. Another stumbling block for participation is excessive formatting from the State. Let us take the example of a joint development zone: it is so regulated by urban planning laws that the number of meetings to be held and the number of possible appeals are completely predetermined. If we want communities to start to get organised, a new order is required. I agree with Cyril Roger-Lacan on this point. We must absolutely step outside the rhetoric that says that metropolitan areas will redistribute, that they are drivers. This interpretation is too narrow and limits them to their geographic scope. All the natural low-density peripheral areas are key to the major challenges we face today and tomorrow, such as biodiversity and the energy and environmental transitions. They are an integral part of the metropolitan area’s dynamism.

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Back from Cahors

Rebalancing

Size, Network and People

Inventing the future of urban highways

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.