Stockholm: a universalist vision of housing tested by shortages

“I believe that if we fail to meet housing demands, we run the risk of a revolt”. This is how Ann-Margarethe Livh, Vice-Mayor of Stockholm responsible for housing, describes the current situation in the Swedish capital, whose housing shortage is now threatening its economic attractiveness.

The shortage affecting Stockholm is a result of the crisis which is affecting Swedish housing as a whole. The public housing system, the aim of which can be summed up by the maxim “dwellings for all”, now seems unable to meet its primary goal. At issue here is the fact that no housing has been built for almost two decades, that demographic growth was boosted by the arrival of asylum-seekers and refugees starting in 2015, and that a significant part of the municipal housing stock was sold to its occupants, resulting in the attrition of said stock. Stockholm must now redevelop this stock if it is to retain its resilience.

1965-1974: one million apartments to provide “dwellings for all”

Having experienced a period of robust economic growth coupled with rapid urbanisation in the years following World War II, Sweden suffered from an acute and widespread shortage of housing beginning in the 1960s. As housing became a key priority for the Social Democratic Party in power[2], the Swedish State approved the Million Programme in 1965, an ambitious initiative to build one million apartments (100,000 per year over ten years), in a country which had a population of eight million at the time. To roll out this policy, the state was able to rely on “generous 100% loan programs and interest subsidies/interest guarantees”[3]. Although the Million Programme was designed as a housing initiative aimed at the middle classes, it quickly became clear that its dense and standardised housing blocks were struggling to attract their target occupants who were not convinced by their architectural characteristics and uniformity (in 1968, the Swedish Home Office expressed the view that “the projects shall have a high degree of uniformity. A strict limit of variants shall be maintained with regard to measurements of building components, stairways, floorplans and configuration in general”[4]). In the early 1970s, as 500,000 of the planned housing units had been built and the country’s economy entered a period of economic slowdown, the Swedish housing stock became surplus and some of the Programme’s housing units remained vacant for a long time[5], particularly in the capital: “In Stockholm, production of the Million Programme units continued well into the 1970s until all planned units were completed, even though the population of Stockholm was to decline from 787,182 in 1965 to a modern low of 647,115 in 1981”[6]. The Million Programme housing units then began to concentrate underprivileged populations, often of immigrant backgrounds: they currently account for 85-90% of inhabitants in the districts targeted by the Million Programme[7]. In the following decade, the Programme was called into question. It was believed to have caused spatial segregation and that its housing had failed to offer inhabitants a suitable connection to the social infrastructure they required.

1990-2010: a housing surplus, economic stagnation, and a stop to construction

From the 1970s to the 1990s, Sweden, which was still resting on the achievements of the Million Programme, continued to have a housing surplus (“in 1995, more than 80% of the municipalities reported an excess supply of housing”[8]), together with significant vacancies in suburban housing stock. In the 1990s, however, there was a pronounced contraction in housing construction due to the drying up of previously significant building subsidies, at a time when Sweden was hit by a credit crunch which forced the Swedish government to spend 4% of its GDP to rescue banks facing bankruptcy[9].

No housing was built for many years, including in Stockholm: “the successive administrations did not build apartments for more than 20 years”, comments Ann-Margarethe Livh. Over this period, the housing stock in Stockholm also suffered from a policy involving municipal housing companies selling public housing to tenants, with a view to financing the creation of new housing made more expensive than in the past by rising construction prices.

This slowdown of construction and the implementation of this public housing sale policy occurred alongside a new period of demographic growth: the population of Stockholm County rose by 350,000 between 2005 and 2015[10]. Concomitantly, many factors contributed to the attrition of housing stock, including the scarcity of land to be developed and the restrictions of some local regulations, which hindered the creation of public housing by municipal housing companies[11].

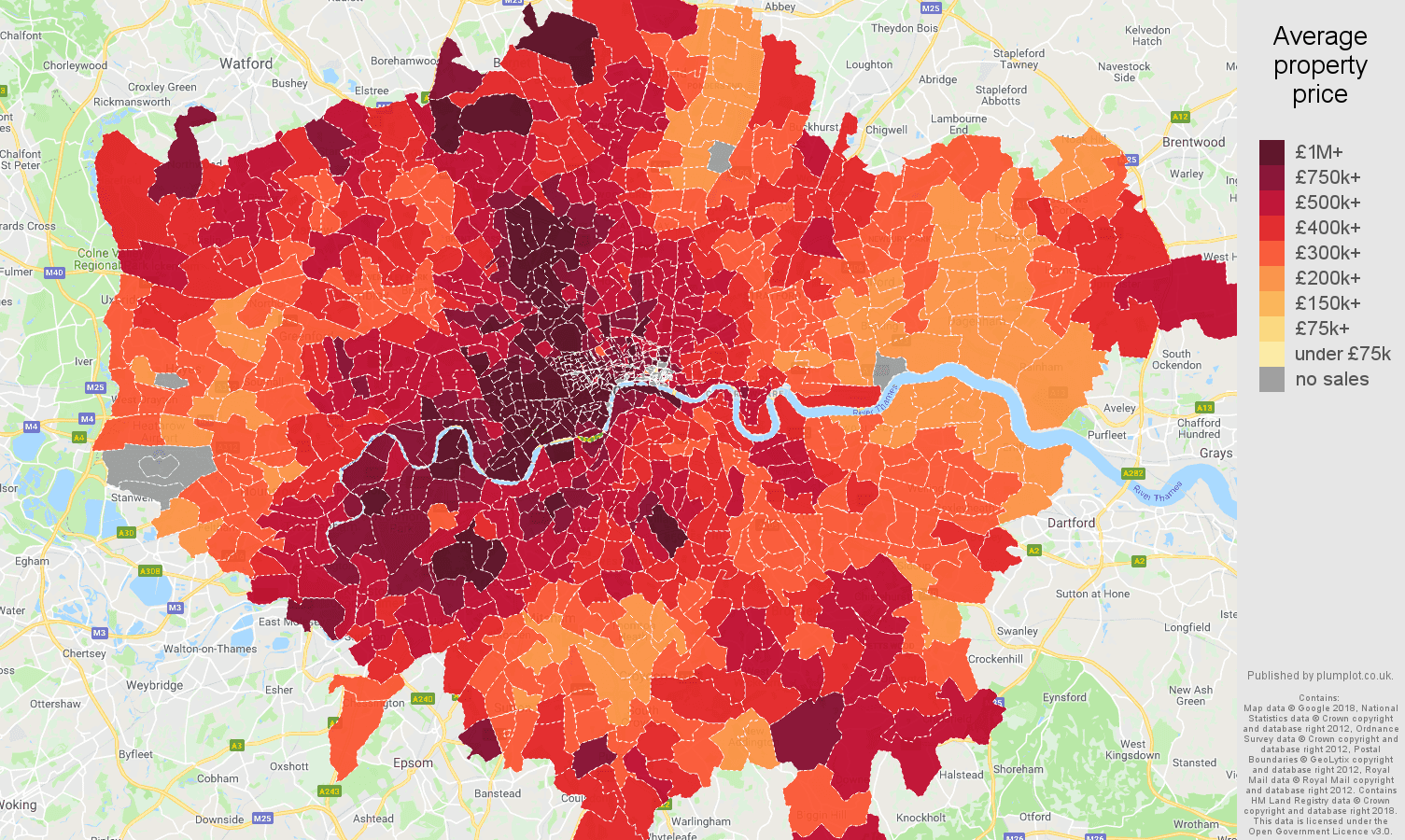

These circumstances were a recipe for a new housing crisis. 255 of Sweden’s 290 municipalities now report a housing shortage[12], and only 44 of the 255 will exit from a shortage situation within three years[13]. At the same time, Boverket, the Swedish national board of housing, estimates that 88,000 new homes must be built each year in Sweden until 2020 to meet current demand[14]. The European Construction Sector Observatory has noted that there is currently “a structural undersupply of dwellings in Sweden despite the high levels of dwelling construction in 2016 and 2017 (63,100 new starts, +34% compared to 2015; 76,000 new starts in 2017, +20.4% vis-à-vis 2016)”, and added that “this situation led to significant increases in house prices, with the house price index soaring by 47.1% between 2010 and 2016 and 8.6% between 2015 and 2016 alone”[15]. Swedish rents rose by 10% between 2014 and 2015[16].

The consequences of this shortage include a lengthening of the average waiting time to obtain public housing in Swedish towns and cities, which currently stands at 5-10 years for a low-rent apartment in the older housing stock, even in outlying districts. At the same time, “rents in new constructions have been rising every year and are today around twice as high as rent in the older stock”[17].

Another tangible effect of the housing crisis is the increasing difficulties that young people are facing to leave the family home and the resulting increase in the average number of adults per household: 25% of young Swedes aged between 20 and 27 currently live with their parents, as opposed to 17% in 1995[21]. The significant amount of time required to obtain public housing and the increase in housing prices have led to a prosperous black market characterised by an increasing number of sub-lets, which are illegal but rarely prosecuted and punished[22] : “If you have a first-hand contract with a relatively low rent, you have a valuable asset, and this can be traded against other apartments, but it might also be possible to sell it on the black market”, explains researcher Hans Lind[23]. These practices result in a reduced number of housing units returned to the public stock and which are currently pending allocation, meaning that in Stockholm less than 10,000 apartments per year are allocated through a municipal waiting list.

Stockholm: a critical shortage of affordable housing

“In the coming years, we will have to hire thousands of people. Our success is entirely dependent on our ability to attract the best talent in the world. […] The first obstacle, as we have already stated many times, is housing availability”: this is how Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon, founders of Swedish company Spotify[27], are seeking to draw attention to the acuteness of the housing shortage that Stockholm is currently experiencing and the devastating consequences it may have on the economic attractiveness and vibrancy of the Swedish capital. This shortage which is affecting Swedish municipalities is at its most acute in Stockholm: the number of people registered on the waiting list of the Stockholm municipal housing company has risen from 100,000 in 2000 to 580,000 today, for a total population of 940,000 inhabitants. The average waiting time on this list is currently 12 years and stretches to 15 years in the most sought-after districts. In 2016, 40,000 people were added to the list while in the same year only 6,900 new apartment rentals were brokered by the Stockholm public housing company[28]. It is currently estimated that “the housing stock needs an increase of 9,000 to 13,000 units annually”[29] in Stockholm. Faced with this need, Stockholm is currently only building 4,000 housing units per year[30].

In addition, rents in newly-built housing are currently much higher than in the past. Jonas Högset, Director of Real Estate and Housing at the Swedish Association of Municipal Housing Companies (SABO), explains that:

“If the average rent is in the region of 1,050 SEK [€100] per square metre per year in Sweden, it is now roughly 1,500 to 1,600 SEK per square metre per year [€142 to €152] for new constructions. This is a huge difference. If we can talk about insiders and outsiders in this system, the insiders are Stockholm’s tenants”.

The arrival of many asylum-seekers beginning in 2015 has further heightened this shortage, revealing an underlying structural crisis. Göran Johnson sums up the current situation in Stockholm as follows:

“As a consequence of revised housing policy in the 1990s, housing construction fell to around 3,000 flats annually in the middle of the decade. This level was far too low from a long-term perspective, which led to population density starting to increase for the first time. When demand for housing once more began to rise, it took several years before construction started to catch up. The result was a housing shortage and soaring house prices. It was not until recently that housing construction once more began to approach the level of 10,000 flats a year, with population growth in the region of 20,000 inhabitants a year. The trend has been an increase in housing construction until the global economic crisis started in 2008, but the trend is now slowing down again”[32].

The shortage in public housing stock has led some to give up the notion of renting a property and to turn to home ownership instead. Yet purchasing a home has also become unaffordable for low-income households and even medium-income households living in Stockholm, where only luxury housing is built to be sold. Jonas Högset analyses the situation: “We are witnessing a rapid rise in prices for the existing housing stock, which have quadrupled since the 1990s. When investing in a condominium, you know that you can spend an additional million because it will be worth two or three in three years. This means that a great number of investments are focused in this condominium segment. Everyone wants to own an apartment because it is the best investment to make. The money is almost free, so those who can invest do so actively in this market. A construction company or developer, regardless of whether they are competent, will always make a profit, because there will always be a market. This is what drives the prices up”.

In light of this situation, Stockholm announced in 2014 an ambitious programme to build 40,000 housing units per year, based on the municipality’s significant control of land (it owns 70% of the land in the capital). A programme to build municipal rental housing with limited rents, known as “Stockholmshus”, was the first initiative in this new approach. The municipality consulted several companies to build 1,000 apartments, selecting those able to provide a quality product at the most competitive price. The selected companies, Svenska Bostäder and Familjebostäder, are currently building 3,500 to 5,000 dwellings by 2020 “without sacrificing either architectural or technical quality”, explains Eva Nygren, President of Stockholmshem[33]. The completed apartments are in line with the features of neighbouring buildings so that they fit into their surroundings. Links between the selected areas and public transportation infrastructure have also been considered for each project. “It is too early to say that the programme is a success”, notes Ann-Margarethe Livh; “we are in the trial phase and the first apartments were only inaugurated six months ago”. Yet the Vice-Mayor responsible for housing admits that the rents of the “Stockholmshus” remain beyond the means of the lowest-income households: “Even these apartments will not have rents low enough that the really underprivileged households could afford them. We must of course build more ‘Stockholmshus’. Through them, we will be able to resolve the problem for many low-income households in Stockholm (teachers, nurses, etc.). However, the more underprivileged (pensioners, etc.) will still not be able to afford the rent. The public sector can do much but it cannot do everything”.

Low-income households, neglected by the notion of “dwellings for all”?

The more urgent and critical need for affordable housing in Stockholm currently concerns around 80,000 people with very low incomes. “At the moment, we have 80,000 people in Stockholm with an urgent need for housing. These include persons aged 35 who have no choice but to live with their parents, large families in apartments which are too small and people in housing on the black market”, explains Ann-Margarethe Livh. Anna Granath Hansson, researcher at the Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan in Stockholm, confirms that “the unmet housing demand derives from all types of households, though low-income groups are hit the hardest”[34]. These particularly vulnerable populations include young people, pensioners, single-parent families and also refugees who have arrived in the Swedish capital following the migration crisis in 2015. While municipal companies have found housing for the 7,000 refugees in Stockholm by leasing temporary accommodation centres to the Swedish Migration Agency, they are now faced with the issue of securing long-term housing solutions for these people: many refugees arriving after 2015 are currently forced to remain in temporary accommodation as they are unable to obtain public housing. “We have resolved the situation for refugees, but only temporarily”, admits Ann-Margarethe Livh. “For young refugees coming from Afghanistan for example, we built very small temporary accommodation which has proven too small for some. They would like other housing, as do the refugee families who are currently living in two-room apartments when there are four or five family members. We have made sure that nobody ends up on the streets but we are facing a crisis today”.

According to Anna Granath Hansson, this situation will not be easy to resolve:

“We will soon find ourselves dealing with chaos. Refugees have no chance to find housing on the regular housing market. Even though the migratory flow has almost dried up, it is still adding to the problem, which is already huge. We have no solution in place. Where are they supposed to go when they leave temporary accommodation?”

Jonas Högset confirms: “the apartments being built today in Stockholm are far from affordable for refugees, even if they are subsidised. It is a very difficult situation”.

Stockholm is failing to build housing that is sufficiently inexpensive to be accessible to these underprivileged populations and in sufficient quantity to contain the rising housing prices. This may be predominantly due to housing construction costs in Sweden. In 2015, these costs were 65% greater than the European average: Sweden has the highest construction prices in the European Union[35]. “Building a multi-dwelling building currently costs almost two and a half times more than it did in the mid-1990s, while other price trends were just over 30 per cent for the corresponding period”, notes SABO[36]. From 2006 to 2016, the construction cost per square metre increased from 22,000 SEK to 42,000 SEK (€2,093 to €3,997) on a national level, while in Stockholm, these costs soared to 49,000 SEK (€4,665) on average. This increase is only partially due to the price of land, which is currently circa 10,000 SEK per square metre on average[37].

How can housing be built more quickly and at a lower cost in Stockholm?

How can construction costs be reduced sufficiently to facilitate and encourage the production of affordable housing in metropolitan areas under pressure such as Stockholm? According to some experts, one avenue would be to slacken the regulatory restrictions applicable to housing construction and to simplify its architectural form. Some are calling for reduced accessibility or a limited use of housing to cut its production cost. Anna Granath Hansson explains the debate currently underway in Stockholm:

“Debate focuses on what is really needed when talking about simple housing. Is it possible to build apartments with only the bare minimum in them? There may not necessarily be a basement, a laundry room, a parking space. On this basis, it is possible to produce housing for much less. It remains highly controversial but is a necessary discussion”.

The idea of designing housing without parking solutions to reduce the cost is particularly interesting as the Stockholm Centre for Transport Studies estimates that “about half of the construction costs for a parking space in a garage (only one floor) are covered by the parking fee, the remainder is funded through increased rents on the apartments. This corresponds to approximately 700–1,500 SEK per square meter which represents about 5% of the apartment’s value”[38]. The idea has generated considerable controversy, that Jonas Högset deems unjustified, particularly as these apartments are aimed at low-income households which, in many cases, do not own a vehicle. “The pooling of garages in major cities is an interesting avenue for cutting costs”, notes Jonas Högset, “but we must remember that car parks are generally not there for rental apartments but rather for privately owned apartments. Removing them would therefore not affect the price of rental apartments”.

This trend to simplify housing also includes a growing interest in prefabrication and standardised production. Mass produced housing is even, according to Jonas Högset, vital for the survival of companies in this sector: “I think that many companies which are currently active on the market will not be around in ten or fifteen years. They will be unable to convert their model to streamline their costs. To be able to cut spending by 50%, you need a radically new way of thinking and to industrialise the production processes”.

Stockholm is now exploring such avenues, in particular for young adults, for example with low-cost, series-built modular housing but “these are generally built where land is cheaper and the resistance to new building projects is not as strong, i.e. rather in municipalities outside Stockholm or in the less attractive suburbs”, explains Anna Granath Hansson. Moreover, these products are aimed at specific populations: refugees, students, young people, etc. It is still a far cry from an affordable housing solution aimed at low-income households in general and which would be rolled out in Stockholm itself, exactly in the districts where there is currently hardly any affordable housing. It should also be noted that these solutions are given temporary planning permission lasting around fifteen years, and are therefore not a long-term solution for affordable housing: “It is quite expensive because the lifespan is too short to motivate investors, but housing must be offered quickly to young people so it is being built on temporary sites”, explains Anna Granath Hansson.

One of the most compelling examples of standardised and mass-produced housing construction which has generated affordable housing comes from SABO, an association federating the 300 municipal housing companies in Sweden. In light of the soaring construction prices at the end of the 2000s, SABO designed Kombohus, a standardised and unique method to produce apartments 25% below the market price, with a view to providing a “good and affordable alternative”[39] for housing. Designed in 2010, the programme has brought about the production of 9,000 housing units since its launch, purchased by 300 municipal housing companies and built in around 100 different municipalities. A Kombohus construction time is eight times shorter than that of normal housing, resulting in significant productivity gains and providing an effective response to the twofold question of how to build at a lower cost and a faster rate, with prices not exceeding €1,200 per square metre for surfaces above the foundations.

This industrialised production does not mean, however, that there is any drop in the applicable standards. “These are the functional requirements that we have set”, explains Jonas Högset. “Turnkey housing blocks with an interior staircase, a lift, limited energy consumption and the possibility of building two to six floors with four apartments of two to three rooms on each floor”. SABO has also imposed high energy requirements. “This is a very stringent requirement and construction companies have shown that they are coping with this while still delivering buildings at a lower price”, notes SABO[40].

The simplified architecture and uniformity of the housing produced makes the product less attractive than unique and custom-built housing to higher-income households, thereby guaranteeing that the Kombohus is accessible to low-income households, even despite the lack of an income threshold typical in Swedish public housing. “It is a radically new model”, remarks Jonas Högset. “The problem is that in Sweden, as in Germany, there is a history of large-scale construction projects, with the ‘Million Programme’ in Sweden and the German ‘Plattenbau’. Nobody wants this anymore, but in our opinion the Kombohus is totally different. It can be part of small-scale projects and can be a perfect fit in the existing community”.

Researchers from the University of Stockholm have observed the positive effect of these products on the average property prices in the districts in which they are built: “Many older people are selling their detached homes and moving to new, accessible rental properties that are easy to look after. Families and couples are buying the houses that they are selling”[41]. This may be one way to solve the problem that is often highlighted in the Swedish media of sub-optimal use of the existing housing stock, particularly due to people living alone or in housing that is much bigger than the average.

If the trend to prefabricate housing and industrialise its production suggests a possible fall in construction prices and a ramping up of housing construction, this is not yet sufficiently significant to enable the most underprivileged residents of Stockholm to access affordable housing.

Public housing vs. social housing

Sweden has a public housing system which, in the spirit of its social democrat fathers, must champion a universal conception of housing rather than a residual vision of public housing stock intended for underprivileged households, as is the case in the social housing systems traditionally in place in Southern European countries and in France. Sweden therefore does not have a social housing system in the strictest sense of the term, defined as a type of subsidised housing aimed at low-income households, and Swedish municipalities must, under Swedish law, provide housing to all their inhabitants, regardless of their income. The apartments rented by municipal housing companies are open to all and are granted to those who have spent the most time on the waiting list, to which everyone can sign up. “The main difference is that the perception of public housing is a tenure form open to everyone and often on a level playing field with private housing”[42], explain Lena Magnusson and Bengt Turner.

While there is a special scheme for persons in great financial difficulty, its reach is extremely limited: some 30,000 social contracts enable such people to live in apartments which are not popular as they are too expensive or are located too far from the centre. The municipality therefore signs a contract with an average term of two years with the municipal company in charge of the housing. While these contracts are available only to persons in financial difficulty, the Stockholm Social Services Department is currently seeing an increasing number of people who are not in this category but who are unable to find housing in the public housing stock.

The Swedish public housing system is the embodiment of the “dwellings for all” concept: “One of the ideological cornerstones in the Swedish welfare state is the idea of equality between different families despite demographic, socio-economic and ethnic characteristics, as well as where they live”[43], explain Lena Magnusson and Bengt Turner. As a consequence, there is only one housing project in Sweden that could be defined as social housing: in Gothenburg, the municipality sells properties it owns on the condition that developers set a rent lower than the market rate for 15 years for part of the housing built. “These below-market rental apartments should then be allocated to households according to special criteria. Even though these have not yet been determined, an income limit is probable”[44], explains Hans Lind.

Yet the Swedish system, aimed at providing housing for wealthy and underprivileged households equally, was not designed to cope with a period of shortage and demographic growth such as Sweden is experiencing today and is no longer able to fulfil this goal. “Paradoxically, the policy that provides housing for all […] creates advantages for higher income people because even people who can afford to buy or rent an apartment in the private market can get a less expensive public housing unit”[45], notes Beacon Pathways. Jonas Högset adds: “the problem is that today our ‘housing for all’ system no longer offers, paradoxically, housing for all”. The municipal housing companies are now caught between two conflicting goals: to accommodate vulnerable families (as well as higher-income households) and to be efficient from an economic point of view, at a time when construction prices are peaking[46].

This situation means that an increasing number of people in Stockholm have no access to either contract housing aimed at highly vulnerable populations in financial difficulty or to public housing at constantly growing prices. “It is very difficult for low-income households to find affordable rental housing, because both private and public apartments are allocated on the basis of waiting lists, the average waiting time is 12 years and very few affordable apartments are put up for rent. In addition, households which have been on the waiting list for a very long time may not be accepted as tenants as their income is deemed too low or unstable”, explains Anna Granath Hansson. It is common to require from potential tenants income that is several times higher than the rent, references and evidence that there is no history of rent arrears[47]. Speaking of this system, Beacon Pathways notes that “far from providing housing for all, Swedish municipal landlords actively avoid housing the poorest and most vulnerable households – at least from the more popular stock”[48]. Some municipal companies even refuse to rent housing to households on welfare, hiding behind a provision in Swedish law that entrusts them with a commercial objective. This means that some low-income households, unable to find housing in the public stock, are forced to turn to municipalities’ social services departments in the hope that they will assist them in finding housing belonging to a private owner or a municipal housing company. Conversely, others resort to the black market, where they can obtain second-hand contracts which are often very expensive, or decide to share housing, generally with no legal security. “Some people live 300 km from Stockholm and travel there every day to work and sleep in their cars”, explains Anna Granath Hansson.

The current affordable housing crisis in Stockholm and other Swedish municipalities therefore stems from the gradual failure of the Swedish “dwellings for all” model, which explains the escalation of fierce debate between those in favour of a social model akin to the Vienna model and champions of the underlying egalitarian conception of the current model. Jonas Högset advocates a continuation of the current system:

“If you accept the principle of housing for all, it also means that many construction companies work for all market segments, both low-cost housing and luxury housing. If you exclude high-income households, the system is no longer housing for all, it is social housing. The current system also brings a social mix to the existing housing stock. We believe that our existing housing for all model remains much more beneficial to the Swedish people than the creation of a new system would be. We are not going to become like Vienna”.

Conversely, according to Anna Granath Hansson, social housing is suffering from the tarnished memories of the Million Programme or the negative image of housing for low-income households in some suburbs of European capitals: “if we want to consider social housing, we must see how it is implemented in Northern European countries today. I think that there are districts that are stigmatised in all countries, but today we can take different action to avoid such situations”.

The option of potentially reforming the current system is, however, coming up against fierce resistance. “The city of Gothenburg attempted to roll out a social housing project in a highly attractive area near the Gothenburg port”, says Anna Granath Hansson. “Only high-income households settled there because the prices were high. The city wished to improve the social mix by enabling low-income households to move there. Politicians have blocked the implementation of this project, the first inclusive housing project in Sweden, in particular under pressure from the tenants’ association – but the city has not given up yet”.

These reservations are more keenly expressed by Swedish public opinion because the shift from a public housing system for all to a residual social housing system would be costly: “We have calculated the annual cost of moving to a social housing system”, explains Jonas Högset. “It is estimated that it would cost the Swedish State €1.5 billion per year to transition to a social housing system similar to that in other European countries”.

Yet social housing may well arrive in Sweden from an unexpected source, as, although municipalities refuse to allocate housing on a means-tested basis, the same cannot be said in the private sector. “Private developers are starting to say that they are not subject to this obstacle of housing for all and are starting to express an interest in social housing”, explains Anna Granath Hansson, particularly as the production of expensive housing, which was previously the bulk of the sector’s production, is now facing a stagnation and even a drop in demand. “Prices have risen very quickly, but today they seem to have peaked in Stockholm, where it is becoming more difficult to sell property”, notes Ann-Margarethe Livh, former Vice Mayor of Stockholm responsible for housing. Anna Granath Hansson confirms: “there is no longer a demand for very expensive housing. Today, many companies in the construction sector are starting to look at the more affordable segment of the market with a view to making the transition”.

An uncertain future

Clear-headed as to the extent of the crisis, Stockholm knows that it has not yet found the solutions that will resolve the shortage of affordable housing it is suffering from today. “For now, we do not know if we will successfully resolve the problem”, admits Ann-Margarethe Livh. “We know that we must tackle it, but as yet we are still considering the means with which to do this”. A result of past decisions – no construction projects for almost 20 years, the sale of many public housing units to their occupants –, the shortage in Stockholm can only be resolved through a long and sustained period of construction of affordable housing, itself subject to a structural decrease in construction costs, which are disproportionate today, specific to Sweden. Lastly, attempts to resolve the shortage of affordable housing must come together with a reassessment, on a national scale, of the past decision to create a universalist public housing system which is today reserved for the wealthiest households.

1 GRANATH HANSSON, Anna. City strategies for affordable housing: the approaches of Berlin, Hamburg, Stockholm, and Gothenburg. International Journal of Housing Policy, 2017. DOI: 10.1080/19491247.2017.1278581

2 HALL, T./VIDÉN, S. The Million Homes Programme: a review of the great Swedish planning project. Planning Perspectives [on-line]. 2005, vol. 20, n°3. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02665430500130233. (Viewed on 4 June 2018)

3 Housing in Sweden: An Overview. [on-line]. Berkeley: Terner Center for Housing Innovation, UC Berkeley, 2017, 21 p. Available at: http://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/uploads/Swedish_Housing_System_Memo.pdf. (Viewed on 5 June 2018)

4 WELIN, L./BILDSTEN, L. The housing market in Sweden: a political-historical perspective. In: Proceedings

of the 9th Nordic Conference on Construction Economics and Organization Gothenburg, Sweden. [on-line]. 2017. Available at: http://lup.lub.lu.se/search/ws/files/29191948/CEO2017_paper_4.pdf (Viewed on 4 June 2018)

5 HALL, T./VIDÉN, S. The Million Homes Programme: a review of the great Swedish planning project. Planning Perspectives [on-line]. 2005, vol. 20, n°3. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02665430500130233. (Viewed on 4 June 2018)

6 ZILLIACUS, C.P. A million new housing units: the limits of good intentions. In: New Geography [on-line].

Published on 7 September 2013. http://www.newgeography.com/content/003811-a-million-new-housing-units-the-limits-good-intentions. (Viewed on 7 June 2018)

7 Ibid.

8 LIND, Hans. The Swedish Housing Market from a Low Income Perspective. Critical Housing Analysis [on-line]. 2017, vol. 4, n°1, p.150-160. Available at: http://www.housing-critical.com/viewfile.asp?file=2467. (Viewed on 8 June 2018)

9 DOUGHERTY, Carter. Stopping a Financial Crisis, the Swedish Way. In: The New York Times [on-line]. Published on 22 September 2008. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/23/business/worldbusiness/23krona.html. (Viewed on 6 June 2018)

10 LIND, Hans. The Swedish Housing Market from a Low Income Perspective. Critical Housing Analysis [on-line]. 2017, vol. 4, n°1, p.150-160. Available at: http://www.housing-critical.com/viewfile.asp?file=2467. (Viewed on 8 June 2018)

11 Ibid.

12 The story of Sweden’s housing crisis. In: TheLocal.se [on-line]. Published on 28 August 2017. https://www.thelocal.se/20170828/the-story-of-swedens-housing-crisis. (Viewed on 5 June 2018)

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 European Commission. European Construction Sector Observatory, country profile Sweden. [on-line]. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/construction/observatory_en. (Viewed on 4 June 2018)

16 GRANATH HANSSON, Anna. City strategies for affordable housing: the approaches of Berlin, Hamburg, Stockholm, and Gothenburg. International Journal of Housing Policy, 2017. DOI: 10.1080/19491247.2017.1278581

17 Housing in Sweden: An Overview. [on-line]. Berkeley: Terner Center for Housing Innovation, UC Berkeley, 2017, 21 p. Available at: http://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/uploads/Swedish_Housing_System_Memo.pdf. (Viewed on 5 June 2018)

18 Ibid.

19 STEINMETZ, Hélène. Les politiques du logement en Europe : comparaisons. Cahiers français, 2015, n°338, p. 8-14.

20 LIND, Hans. The Swedish Housing Market from a Low Income Perspective. Critical Housing Analysis [on-line]. 2017, vol. 4, n°1, p.150-160. Available at: http://www.housing-critical.com/viewfile.asp?file=2467. (Viewed on 8 June 2018)

21 The story of Sweden’s housing crisis. In: TheLocal.se [on-line]. Published on 28 August 2017. https://www.thelocal.se/20170828/the-story-of-swedens-housing-crisis. (Viewed on 5 June 2018)

22 LIND, Hans. The Swedish Housing Market from a Low Income Perspective. Critical Housing Analysis [on-line]. 2017, vol. 4, n°1, p.150-160. Available at: http://www.housing-critical.com/viewfile.asp?file=2467. (Viewed on 8 June 2018)

23 Ibid.

24 CROUCH, David. Pitfalls of rent restraints: why Stockholm’s model has failed many. In: The Guardian [on-line]. Published on 19 August 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/19/why-stockholm-housing-rules-rent-control-flat. (Viewed on 6 June 2018)

25 LIND, Hans. The Swedish Housing Market from a Low Income Perspective. Critical Housing Analysis [on-line]. 2017, vol. 4, n°1, p.150-160. Available at: http://www.housing-critical.com/viewfile.asp?file=2467. (Viewed on 8 June 2018)

26 Ibid.

27 Spotify SE. We have to act or get bored! An open letter from Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon, founders of Spotify. In: Spotify on Medium [on-line]. (11 April 2016) Available at: https://medium.com/@SpotifySE/vi-m%C3%A5ste-agera-eller-bli-omsprungna-383bb0b808eb (Viewed on 6 June 2018)

28 The story of Sweden’s housing crisis. In: TheLocal.se [on-line]. Published on 28 August 2017. https://www.thelocal.se/20170828/the-story-of-swedens-housing-crisis. (Viewed on 5 June 2018)

29 JOHNSON, Göran. Affordable Housing – Position Statements for Stockholm [on-line]. Stockholm:

Stockholm County Council Office of Regional Planning, 2010, 20 p. Available at: http://www.eurometrex.org/Docs/Expert_Groups/Affordable_Housing/Affordable_Housing_Position_Statement_Stockholm.pdf. (Viewed on 7 June 2018)

30 GRANATH HANSSON, Anna. City strategies for affordable housing: the approaches of Berlin, Hamburg, Stockholm, and Gothenburg. International Journal of Housing Policy, 2017. DOI: 10.1080/19491247.2017.1278581

31 Ibid.

32 JOHNSON, Göran. Affordable Housing – Position Statements for Stockholm [on-line]. Stockholm:

Stockholm County Council Office of Regional Planning, 2010, 20 p. Available at: http://www.eurometrex.org/Docs/Expert_Groups/Affordable_Housing/Affordable_Housing_Position_Statement_Stockholm.pdf. (Viewed on 7 June 2018)

33 Stockholmshem. Stockholmshusen [on-line]. Available at: http://www.stockholmshem.se/Nyproduktion/Stockholmshusen/. (Viewed on 8 June 2018)

34 GRANATH HANSSON, Anna. City strategies for affordable housing: the approaches of Berlin, Hamburg, Stockholm, and Gothenburg. International Journal of Housing Policy, 2017. DOI: 10.1080/19491247.2017.1278581

35 SABO. SABOS Kombohus, forcing construction prices down by 25%. [on-line] Available at: https://www.sabo.se/document/sabos-kombohus-forcing-construction-prices-down/. (Viewed on 7 June 2018)

36 Ibid.

37 https://www.macrovoices.com/macrovoices-content/list-research-roundup/1447-the-swedish-housing-market-primer-dec-20th-2017/file

38 https://www.trafikverket.se/contentassets/773857bcf506430a880a79f76195a080/forskningsresultat/effect_of_minimum_parking_requirements.pdf

39 SABO. SABOS Kombohus. [on-line] Available at: https://www.sabo.se/in-english/sabos-kombohus/. (Viewed on 7 June 2018)

40 Ibid.

41 SABO. How Sabos Kombohus affects local housing market. [on-line] Available at: https://www.sabo.se/document/sabo-analysis-how-sabos-kombohus-affect-local-housing-markets/. (Viewed on 7 June 2018)

42 MAGNUSSON, L./TURNER, B. Municipal Housing Companies in Sweden – Social by Default. Housing, Theory and Society [on-line]. 2008, vol. 25, n°4, p. 275-296. Available at: https://www.tenlaw.uni-bremen.de/literature/HTS_vol25_no4_2008sweden.pdf. (Viewed on 5 June 2018)

43 Ibid.

44 LIND, Hans. The Swedish Housing Market from a Low Income Perspective. Critical Housing Analysis [on-line]. 2017, vol. 4, n°1, p.150-160. Available at: http://www.housing-critical.com/viewfile.asp?file=2467. (Viewed on 8 June 2018)

45 Beacon. Housing Affordability in Europe – Background: Housing in Sweden – Information from desktop research [on-line]. Stockholm: Beacon, 10 p. Available at: http://www.beaconpathway.co.nz/images/uploads/Background_Housing_in_Sweden.pdf. (Viewed on 8 June 2018)

46 MAGNUSSON, L./TURNER, B. Municipal Housing Companies in Sweden – Social by Default. Housing, Theory and Society [on-line]. 2008, vol. 25, n°4, p. 275-296. Available at: https://www.tenlaw.uni-bremen.de/literature/HTS_vol25_no4_2008sweden.pdf. (Viewed on 5 June 2018)

47 Beacon. Housing Affordability in Europe – Background: Housing in Sweden – Information from desktop research [on-line]. Stockholm: Beacon, 10 p. Available at: http://www.beaconpathway.co.nz/images/uploads/Background_Housing_in_Sweden.pdf. (Viewed on 8 June 2018)

48 Ibid.

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Helsinki : Planning innovation and urban resilience

Forget 5th Avenue

Long live urban density!

The ideal culprit

Behind the words: density

Behind the words: Affordable housing

German metropolises and the affordable housing crisis

Berlin Focus

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.