The liveable city, a tool for the shaping of urban imagination : dialogue between Limin Hee and Antoine Picon

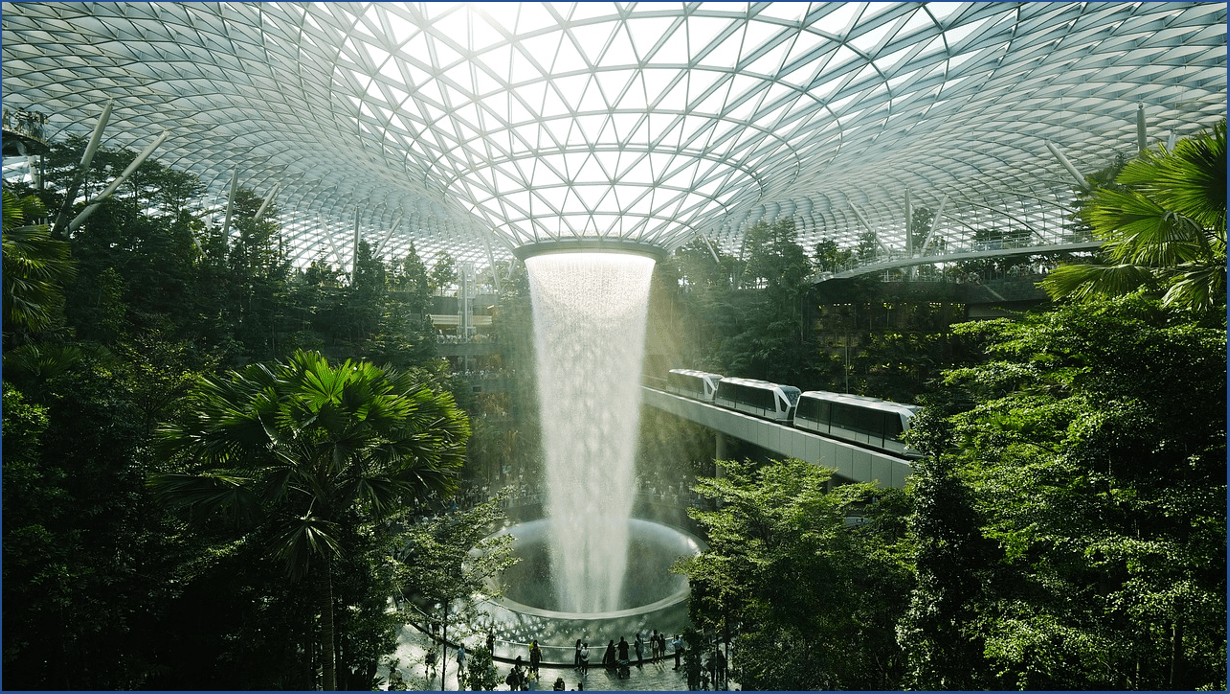

From 10 to 12 July 2019, La Fabrique de la Cité organized an urban expedition to Singapore and welcomed Limin Hee, Director of research at the Centre for Liveable Cities, and Antoine Picon, Professor of the history of architecture and technology at Harvard University and École des Ponts et Chaussées, for a debate entitled: “The liveable city: a tool for attractiveness and the shaping of urban imagination”. “Tropical city of excellence”, “biophilic city in a garden”, “smart city” and “liveability”: what realities lie behind Singapore’s storytelling? Will the city-state’s citizens embrace the visions proposed by their leaders in the long run? Finally, in a context of climate change, are liveability and sustainability compatible? While the digital transition is a vector for performance and opportunities, its rising energy cost runs counter to the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Dialogue between Limin Hee and Antoine Picon.

Singapore has developed its own definition of “liveability”, which encompasses much more than quality of life. What does it consist in? How does the city-state shape this vision on its territory?

Limin Hee: Singapore has had to deal with the challenges of urbanization throughout its history: overcrowded slums, high unemployment, water shortages, floods, polluted rivers, traffic congestion… There are 5.61 million inhabitants in Singapore living on a 722km² territory with very limited natural resources, yet with essential needs that a city-state must cater to: defence, accessibility, and water provision, amongst other things.

Singapore has become a highly liveable, dense, and sustainable city, with much greenery and waterbodies. Great importance is attached to evolving towards a car-lite city: the Land Transport Masterplan 2040 was designed to be as comprehensive as possible. The goal is to shift from a car-centric island to a people-centric one by encouraging active mobility modes and reducing travel times.

In order to complete this vision of a liveable Singapore, we created the Singapore Liveability Framework[1], which goes beyond mere quality of life. This element is completed by two other pillars: a competitive economy and a sustainable environment. The implementation of the framework has implied rethinking the system, as evidenced by the careful association of dynamic urban governance and integrated master planning and development. The Centre for Liveable Cities conducts research based on workshops, site-specific studies, international survey of best practices in other cities – Munich or Vancouver, for instance –, and inputs from both local and international experts. We aim at making the liveable city a reality.

To that end, we hold multi-stakeholder workshops and conduct iterative research processes involving the public sector, companies, and citizens. In the framework of the “Heartland Tampines” study, we aimed for a user-centric approach by creating quality public spaces with greenery and better connectivity for cyclists between towns – towns are peripherical centralities. Regarding the “Reimagining Orchard Road” study (a street that is not only a commercial artery but one of Singapore’s major public spaces), we moved away from the traditional approach of improving the shopping experience, to ask instead: “what should Orchard Road be?”. The study aims to reclaim streets for people and transform them into liveable spaces desired by the community.

Although the approach to public space is very different in Singapore and in the West, public life, its appropriation and its practices are key. While people do not protest on the streets, space can be used in a friendly manner to negotiate some of the agenda. A few years ago, the government announced the redevelopment of a nature area. Some nature advocacy groups mobilised, organised tours, and conducted research. This mobilisation resulted in a report that was then handed to the public authorities; faced with active citizen advocacy, the government later decided to preserve the area, at least for now.

Singapore’s urban model is based upon the deployment of the “smart city”. Yet tech-based discourses are nuanced if not contradicted by reality; tech sometimes only moves or even exacerbates existing problems. What realities lie behind these political promises of a pleasant city?

Antoine Picon: Tech is not fundamentally changing the world but rather is transforming the city into a laboratory: for the first time, we are able to conduct an in-depth study of multiple processes we were not knowledgeable about. It may be true that we will not witness the end of congestion in the short term; however, censors and other digital devices now allow us to understand mobility at a much finer grade.

To come back to the notion of liveability, it cannot be an absolute, regardless of all the metrics and comparisons we may have. Liveability is a political project. In the case of the City Brain Project in China, citizens are ready to trade security in exchange for population control. It is certain that this project addresses liveability, but not in terms that will convince Europeans.

As for our developed cities, I don’t believe we are going to much improve their liveability. The greatest challenge that may lie ahead concerns very large metropolises in emerging countries. Tech could bring interesting solutions to foster inclusion. We may think that more agile technologies will be able to transform slums and to bolster a smoother transition than demolition and reconstruction. All in all, liveability is not going to create a paradise, but it can definitely improve cities.

Digital tools can help us manage resources; however, they consume a lot of energy and emit large amounts of CO2. Is the liveable city’s technological dimension compatible with the pursuit of sustainable development?

Antoine Picon: There seems to be a discrepancy between Singapore’s awareness of its own fragility as an island and the story it is telling about its economic growth, in a world that is more and more sensitive to environmental issues. There might be a contradiction there. I think a smart city is necessarily a green city; I don’t see how a non-environmentally sound “smart city” could be “smart”. Currently, the use of digital technologies, including the cloud, represents 4% of the world’s energy consumption and carbon emissions. Most concerning is that this consumption is growing by 10% annually. Although using digital technologies seems free and inconsequential, it imposes a cost on the planet and the environment. We must head from digital hubris to digital frugality by modifying our behaviour. “Green” and “smart” do not converge completely, but as the city of the future will both be digital and about nature, their convergence is becoming a priority.

“The digital revolution is not fundamentally a technological revolution: it is a cultural one.”

– Antoine Picon

For a long time, Singapore has felt the need to develop a narrative: “tropical city of excellence” in the 1990s, “city in a garden” from 1998, and now “liveable city”. To what extent does the storytelling of a city contribute to its governance?

Limin Hee: We have worked a lot on engaging and exchanging with citizens in order for them to see meaning in infrastructure. Our aim has been to build a narrative that evolves over time: Singapore is not just a green city, it is “a city in a garden”. We are now transitioning not towards a city “with nature” or “of nature”, but towards “a city in nature”. This is because we exist alongside biodiversity and learn to live with animals; indeed, in Singapore, hornbills are not seen as a nuisance when they make noise in our backyards. We worked on naturalizing streams in order for people to come closer to the water and appreciate these areas as part of the urban playground. The concept of “city in nature” is becoming a basis for Singapore’s inhabitants. In that respect, the presence of nature is not just infrastructure, but infrastructure that has meaning in Singaporeans’ daily life.

Antoine Picon: Isn’t Singapore a gigantic storytelling adventure, with a tremendous ability to manipulate symbols? This ability is directly linked to the mode of governance. This does not correspond to the classical democratic process. Singapore’s model is rather about creating consensus. Interestingly, this is in part related to the Confucian tradition, but it also has to do with the age of Internet. Governance is evolving. Dominique Cardon, a French sociologist, has extensively written on democracy in the age of Internet; he argues that stories generate consensus. Digital technologies challenges Western democracies’ classical political systems. In some ways, these kinds of very efficient connections between storytelling, consensus building, and infrastructure development may seem frightening to Westerners.

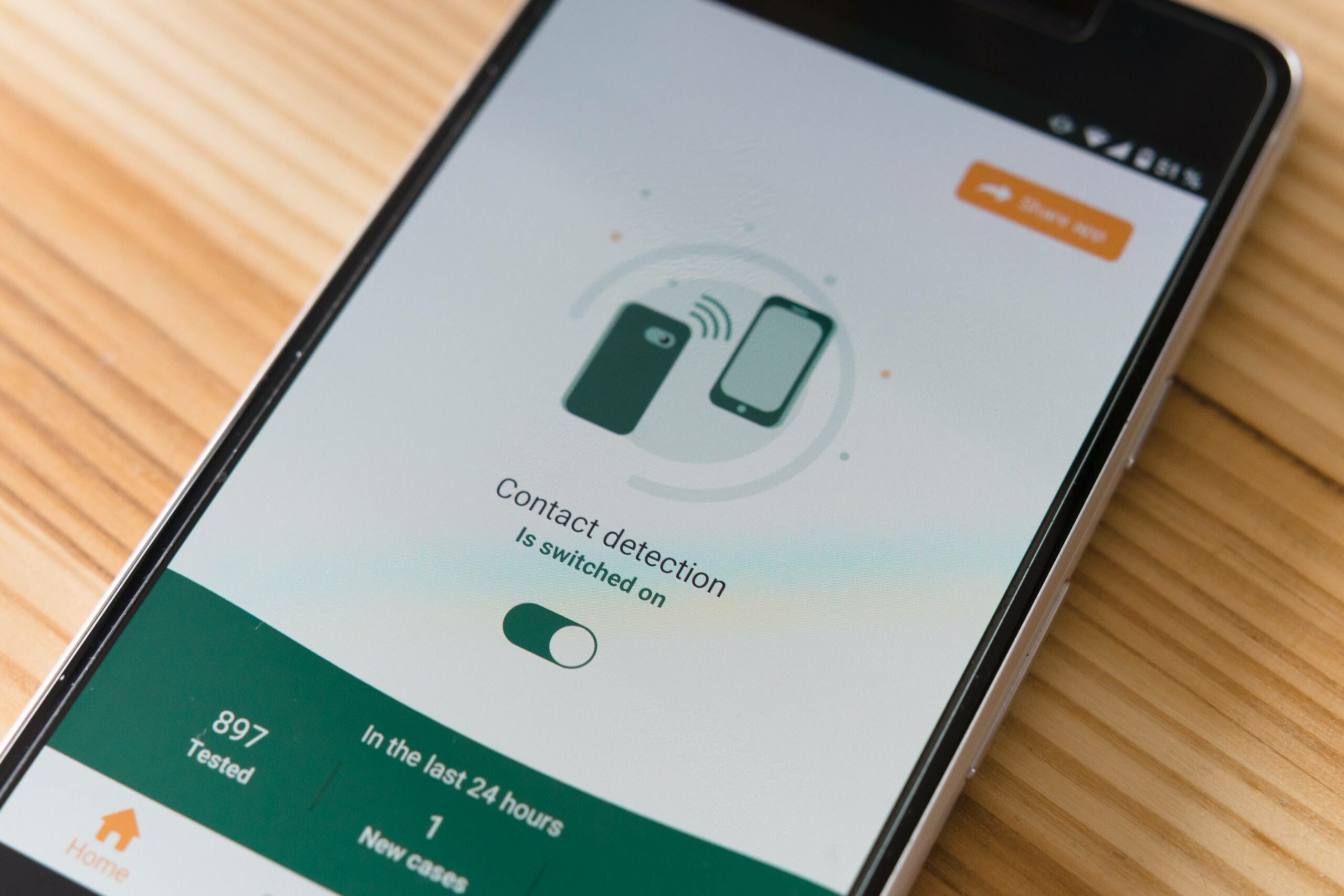

To what extent do “smart city” devices and new digital players disrupt and renew the current urban social contract?

Limin Hee: All city players collect urban data. What is important is who collects, manages, and processes it. The regulatory framework that collectors must abide by, as well as the purpose served by the use of urban data, are also essential elements. In Singapore, there is a constant need to innovate to solve problems. Thus, we use regulatory sandboxes, which are places where experimentations are conducted over a defined period of time in order to see what works and what does not, before the regulators jump in. The goal of such laboratories is to provide better services for people. We are in a transition period where new players are coming in with new business models and will have to adapt these models to the Singaporean context.

Antoine Picon: We must keep in mind that it is not the first time that the private sector has been disruptive. Early on, in the electricity industry, the first multinational firms caused states a tremendous problem: as major players, they would not obey classical state rules. Currently, very robust negotiations are taking place, in particular with Airbnb. Singapore is an interesting case, as there is still strong trust in the government. An equilibrium between digital platforms and political powers (municipalities and states) must be established.

Moreover, the situation is more complicated than it appears. It is not only about “the big bad digital players coming on the scene”: our expectations have changed. Amongst other things, the notion of privacy is evolving very fast. Take the quantified self: we willingly give more and more information to applications like Fitbit. To put it briefly, it is not only about the social contract, but also about the people involved in this contract. A new kind of individual has been produced by tech. This major shift results in a need to change the way we think of politics. The digital revolution is not fundamentally a technological revolution: it is a cultural one. Tech is changing the very way we understand society and communicate with one another, for better and for worse. Social networks are very emblematic of this shift: they have brought new and interesting things, as well as a great deal of terrible things. Nevertheless, it is very difficult at present to fully unpack the political consequences of the transformation of the social contract in the age of social networks. It cannot be the same as the one Jean-Jacques Rousseau theorized in his time.

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Toronto: How far can the city go?

The political and technological challenges of future mobilities

Nature in the city

Viktor Mayer-Schönberger: what role does big data play in cities?

Thomas Madreiter: Vienna and the smart city

Vienna

Breathless Metropolises

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.