The mid-sized cities at high speed

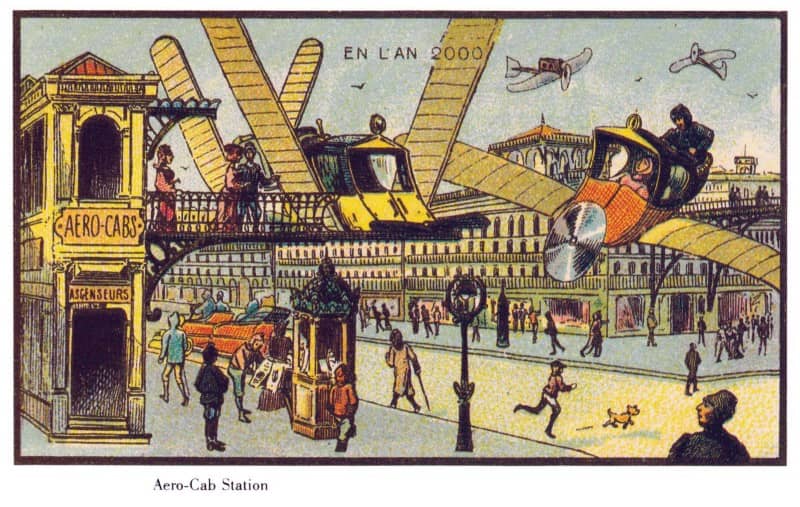

Gradually, the French territory was irrigated: Brittany, Aquitaine, then the Mediterranean coastline. The European capitals then joined the race and London was connected in 1994, followed by Italy and Spain in the 2000s. In total, no less than seven train generations have been on the rails, carrying nearly three billion passengers throughout France.

All of France? Well, although all major French cities have a TGV station, serving medium-sized towns remains an important issue. In general, transportation infrastructures can promote the economic development of a region, especially if it is landlocked. Opening up to an expanded labor market, access to larger tourist flows, and increased national attractiveness: the promises are important for a community, but the effect can also backfire: it can also significantly increase real estate prices and service costs and change local employment structures in favor of incoming and outgoing flows, thus unbalancing the territory’s markets. Capturing the flows and controlling their growth is therefore crucial to fully benefit from a TGV connection.

The rise of homeworking during the pandemic is already redefining the boundaries and refocusing the attraction on medium-sized cities reachable by TGV. The SNCF has even recently proposed a homeworking package, facilitating weekly trips between two cities. Access to medium-sized cities is therefore at the heart of the debate on major TGV projects. Promised by Emmanuel Macron last week, the Paris-Normandy axis should get a high-speed line, as well as the Bordeaux-Toulouse and Montpellier-Perpignan links.

Beyond the still distant timeframe of these projects, it is important to question the access of the medium-sized cities neighboring the planned lines. In other words, we must avoid at all costs the “tunnel effect”, which would deprive small towns of these fast routes. The stakes are high, and they are not new. Libourne, Bourg-en-Bresse, Béthune, Arras or even Vitré were worried in 2017 about the continuation of their TGV stations. The mayor of Libourne, committed to the protection of his line, announced a “vital fight for 4000,000 inhabitants“.

Beyond a simple question of accessibility, it is also the financing of the lines and the indebtedness that the new infrastructures generate. Participation of the municipalities, the State, the SNCF and other partners: so many conditions to be set, regulated and renewed to ensure the sustainability of a project.

“A few days ago, Emmanuel Macron said, “Long live the TGV!” And the subject is not about to dry up, reinforced by the growing attractiveness of medium-sized cities and areas on the outskirts of major metropolises. Mobility is always an issue for medium-sized cities, and whenever they benefit from a connection to a high-speed train service, they can hope to return to a positive trajectory. This is also the point of view of the mayor of Libourne, who describes his city as “peri-metropolitan” and talks about the challenges of his territory, where quality territorial cooperation is taking place.

Find this publication in the project:

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Back from Cahors

Rebalancing

Size, Network and People

Sending out an SOS

Behind the words: telecommuting

Behind the words: urban congestion

The political and technological challenges of future mobilities

Inventing the future of urban highways

“Dig, baby, dig”

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.