The political and technological challenges of future mobilities

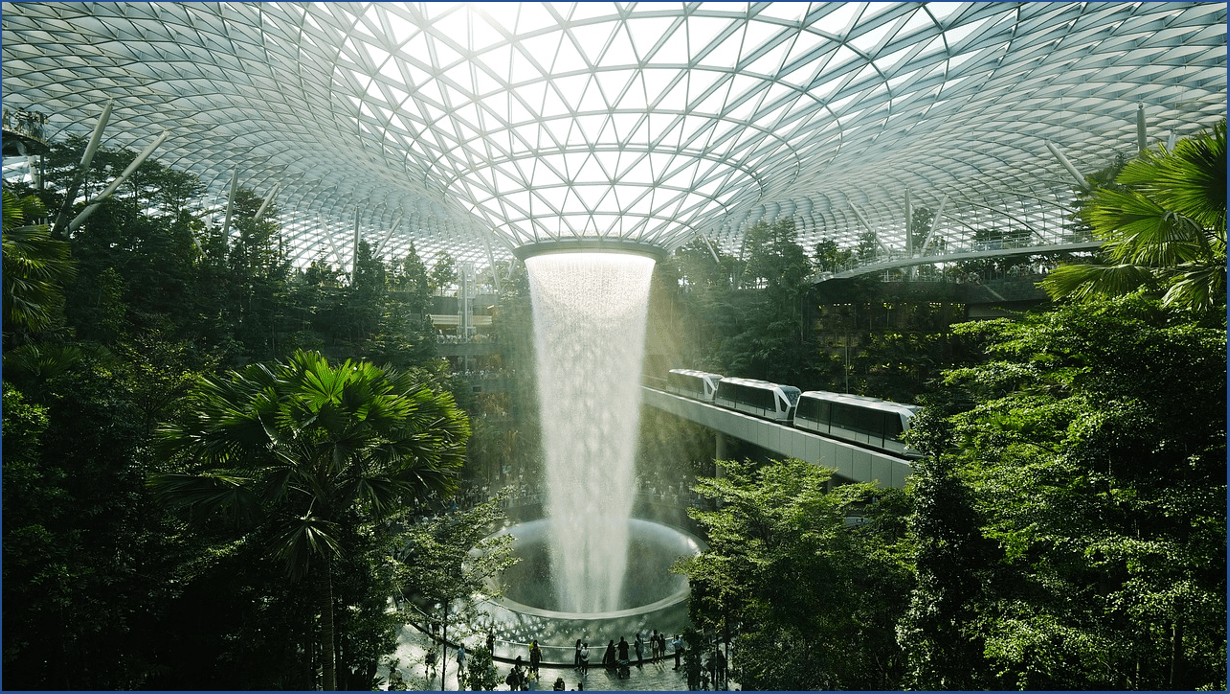

Flying taxis, hyperloop, e-scooters, autonomous vehicles… These are the images conjured by the term “future mobilities”, which, despite great technological promises may not be able to solve nuisances involved by current mobility paradigms. To what extent will these innovations be able to address actual mobility needs? The biggest innovation in the area of mobility may instead come from policy. To go back to basics, to what extent can pricing and infrastructure management and planning lead to post-carbon mobility? Jean Coldefy, mobility expert, Niels de Boer, programme director of the Centre of Excellence for Testing & Research of Autonomous Vehicles (CETRAN – Nanyang Technological University), Lam Wee Shann, chief innovation and technology officer at the Singapore’s Land Transport Authority, and Karina Ricks, director of mobility and infrastructure at the City of Pittsburgh, brought their insight on these questions during La Fabrique de la Cité’s urban expedition to Singapore that took place from 10 to 12 July 2019.

LFDLC : How do Singapore and Pittsburgh articulate policies and technological innovations?

Lam Wee Shann: Singapore envisions a Smart Nation that is a leading economy powered by digital innovation, and a world-class city with a Government that gives our citizens the best home possible and responds to their different and changing needs. This, to put it in a plain language, is about using digital technology to improve the life of people and drive our economy.

The work we do in land transport also forms a key pillar of this national effort. For example, we adopt a two-pronged approach in managing road congestion. On the supply side, we control the population of cars through the issuance of a Certificate of Entitlement (COE). A COE must be acquired before an individual or company can own a vehicle; this applies to motorcycles, passenger cars, and freight vehicles. The total number of COEs is managed by the Government. The price of the COE is determined by market forces through a bidding process and each successful COE represents a right to vehicle ownership and the use of our limited road space for the next ten years. The number of COEs released is determined by the number of vehicles taken off the road in the preceding three months, the allowable growth in vehicle population and adjustments if any. One year ago, in Feb 2018, we adjusted vehicle growth rate, except for commercial vehicles, to zero, which means that the COE supply will be determined solely by the number of vehicles deregistered, i.e. in order to introduce a new vehicle into the system, another vehicle must be deregistered. The other road congestion measure we have implemented in Singapore is the Electronic Road Pricing (ERP).

Before we implement regulatory policies managing car traffic, we must make sure that we have a good standard for our public transport and transport fares are kept low so that people can move around the city at an affordable price. The key driver of our car-lite policies is the impact of congestion on people’s lives and on the economy. As for public transport, we manage demand by encouraging people to use the transit network, but we also work on increasing the supply by building more bus and subway infrastructure. Our aim is to work on both demand and supply; to that end, we tap on technology to push the boundary.

« Before we implement regulatory policies managing car traffic, we must make sure that we have a good standard for our public transport and transport fares are kept low so that people can move around the city at an affordable price. »

Karina Ricks: We know in Pittsburgh that innovation is the child of necessity. Our necessity is renewing our economy from an industrial economy to a technological one. Besides necessity, innovation is also the child of curiosity. What I mean by that is that not every innovation addresses a need. Sometimes, it is just an engineer wondering: Can I do it? Can I make this happen? It is necessary to know the difference between an innovation that addresses a need and one that is undertaken because it is something fun to do. For example, autonomous vehicles must address real mobility gaps. Therefore, we organized a conference to which we invited people with mobility concerns: single mothers, workers of the night-time economy, people who are now coming out of prison, etc. We asked them: “Where did the mobility system fail you?” To the technologists, we ask: What is the problem that you are solving for? To the others, especially politicians, it is necessary to remind them to keep an open mind about technology, to try new things and think of how they would fit into urban environments.

Then, another question must be answered: does the new mobility serve all users? Users are creative: they put small kids on the bike’s handle, take two or three passengers on the scooter. But these vehicles are not set up for this kind of travel. It is our role, as public authorities, to push the shared-mobility industry to be more creative so that all vehicles can provide safe travel and adapt to different profiles and practices.

Niels de Boer: Singapore follows the triple helix model of industry, academia, and government working together. The Centre of Excellence for Testing & Research of Autonomous Vehicles, which is part of Nanyang Technological University, has for example partnered with many private sector players and is supported by Singapore’s Land Transport Authority. This triple helix model is at the root of Singapore’s innovation-building. While developing a technology, it is necessary to work on the legal requirements and the technical standards in parallel: they support each other. Otherwise, by the time you get the technology, it cannot be deployed due to a lack of legal framework.

LFDLC : How do you address the economic and social issues born of mobility?

Karina Ricks: In Pittsburgh, we think of mobility not only as physical transportation but also as economic movement. Therefore, we follow several imperatives. Our guiding light is safety: no one should die travelling on our city streets. The second imperative is access: how do we make sure that all our households can access all of their needs for their daily life? We use as an indicator the ability to get fresh fruit and vegetables within 20 minutes from door to door. Third comes affordability: we add housing costs, transportation costs, and energy costs. All together, these three elements should not exceed 45% of a household’s income. At the lower income levels, we offer subsidized housing to compensate for high transportation costs. For higher income levels, housings costs may be high relative to income, but transportation costs are low. Then, health and joy are important in a city. We believe walking and cycling are the most enjoyable ways for very short distance trips. Is it easy to cross the streets, is it easy to bicycle? Do you meet your community, and what kind of experience do you have when going from point A to point B? Design is the last element. Our streets should tell the story of what is important to our city. Do they say that it is important that you race from one place to another, or do they say that it is important that you come together, enjoy each other, and meet your neighbours?

Lam Wee Shann: Today, Singapore has less than one million vehicles, but more importantly, we have about ten million passenger trips per day in our public transit network. There are quite a few challenges that shape our mobility policies. Our first concern is space management. The second is about demographics. Singapore will have to cater to an increasing population and rising transport demand, not to mention rapid ageing of its population; by 2020, the number of elderlies will increase to close to 3.4 million (Singapore’s current total population is estimated to 5.6 million). Population ageing also challenges the labour force. Finally, safetyand sustainability will frame mobility for the next twenty years. This is why we are promoting a car-lite environment. Our aim is to nudge people to use public and shared transportation, and to encourage walking and cycling as much as possible. The use of privately-owned vehicles should be minimised as much as possible.

To control car usage, we have implemented road pricing, the implementation of which dates back to 1975. In 1975, we had the “Area Licensing Scheme”, manually-checked cordons were set up within Singapore’s central area: all vehicles coming in would pay a fee, except high-occupancy ones. In 1998, we transitioned to “Electronic Road Pricing”, which allowed for the replacement of the Area Licensing Scheme’s toll booth by gantry-based cordons. Vehicles passing those cordons have to pay a charge during peak hours. The charge is reviewed quarterly based upon the speed on the road: if the average speed drops below a certain threshold, we increase the charge. If the speed goes up, we moderate the charge. Therefore, charges are determined by usage and congestion.

Jean Coldefy: Singapore is a utopia for European cities. It has achieved something that can hardly be done in other metropolises: developing a very efficient mobility system avoiding car use and putting at the same time high pressure on car ownership and usage with high results. The results are impressive: if you compare France with Singapore, the car-to-inhabitant ratio is 2.5 lower in the city-state. Why is car usage a problem? The biggest problem cars are causing is about space occupancy. With limited surface area, land is Singapore’s most important resource, and that is quite logical that you have implemented such a policy.

The other very important point is that all competencies are within one entity’s hands: LTA. European and American cities face huge governance problems, as many people commute from outside the city’s perimeter. This multi-layering and multiplicity of jurisdictions challenges the ability to operate public space, for managed lanes, traffic lights, bus priorities, etc.

Third, in Europe, finding financial resources is a major challenge in the improvement of existing mobility services or the provision of new travel options. These are the three main elements that must be considered.

« The biggest problem cars are causing is about space occupancy. With limited surface area, land is Singapore’s most important resource. »

LFDLC : Both Singapore and Pittsburgh are working on developing autonomous vehicles. To what extent can they help improve urban mobility and what challenges must still be addressed in this regard?

Lam Wee Shann: As previously mentioned, Singapore’s population is rapidly ageing. We face a very tight manpower situation: the average local bus captain is in their mid-fifties. In this context, autonomous vehicles would be of great help to alleviate the constraints on the labour force. It would also increase transport safety and provide better public transport service. But we don’t believe privately-owned autonomous cars would be a solution. They would simply add to congestion and could result in more space required for parking.

Autonomous mobility requires a lot of planning, so we have formed committees that include government representatives (planners, economists, researchers, etc.), private sector players and experts. Together, we have built our vision for both human mobility and the mobility of goods. Hopefully logistics vehicles will operate during silent hours, but the noise and lighting will have to be calibrated for autonomous driving. Even the business model will have to change somehow. Autonomous driving is not only about technology but also about enablers: we will have to set standards because there is no global standard on the use of autonomous vehicles; public acceptability, too, is a challenge.

Niels de Boer: Research and development for autonomous vehicles highly depends on the testing framework, which helps come up with technical standards and testing procedures. Today, only three stages of testing can be covered by insurance companies. No insurance company is ready to take responsibility for stages beyond those ones, as the testing framework remains undefined. It is not so much a matter of liability, but they need to know what must be insured. Can they calculate a premium that makes insurance effective? Unfortunately, we don’t know what the risk is. Indeed, risk is traditionally calculated based on statistics, but the volume of our fleet is not large enough to allow for the collection of the statistics needed to assess risk.

From a technical perspective, traditional cars are assessed using a physical test. Today, as we replace the driver by software as core operation control, we need to find new ways of assessing whether the software is ready. Simulations and tests on our test rack enable us to monitor development: we assess performance and the understanding capacity of vehicles on the road. In early stages of testing, developers are mostly preoccupied with accident risks. But what is more complicated is operating in and adapting to traffic. This is why CETRAN works a lot with the traffic police to examine behaviours and to look at how risk can be mitigated. Because passengers are as important as pedestrians, it is also necessary to teach autonomous defensive driving in order to avoid emergency braking. Before teaching, we must define the concept: this is where the challenge lies.

The more data is collected, the more autonomous vehicles can learn. While R&D has enabled widespread collection of data, the sharing of this data raises new challenges. We must indeed keep in mind that this whole industry is big business for venture capitalists, with intellectual property the key asset of companies. Therefore, how can we grant access to the data without disclosing intellectual property? This question must be answered.

« The more data is collected, the more autonomous vehicles can learn. While R&D has enabled widespread collection of data, the sharing of this data raises new challenges. »

Karina Ricks: Pittsburgh has had autonomous vehicles since 1985. Carnegie Mellon University was indeed the place where the first autonomous vehicle testing occurred. But we’ve had a great growth of autonomous testing in the last two years: today, five companies are testing more than 60 vehicles on the streets.

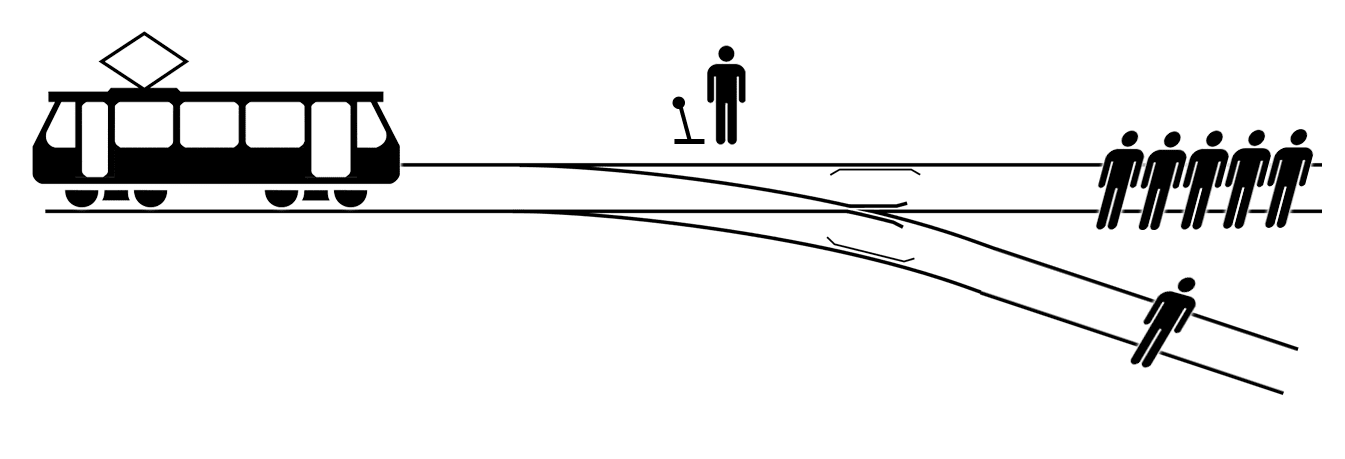

One aspect is not mentioned enough: the ethics. Do you know the Trolley Dilemma? The trolley is racing down, and you have to pull the lever to make it go either left or right. If it goes right it goes over your mother, if it goes left it kills four strangers. Which one do you choose?

As a human, you’ll most likely be making a very quick decision. For the autonomous vehicle, it is a premeditated programme decision. How is that decision going to be made? Will it be made by the equipment manufacturer, the government, or the people? Autonomous vehicles today only recognize pedestrians. They do not recognize a pedestrian carrying a child on their shoulders as a person. If the pedestrian is walking around in a costume, the autonomous vehicle doesn’t know it is a person either! These are the limitations of artificial intelligence, as it is only as good as the intelligence that it was fed with. So we must feed it with every possible scenario, as it doesn’t think the way humans do. There is still a long way to go before we have commercially available autonomous vehicles.

One thing that makes pedestrians use the cross path is that they are afraid that they would be hit by a car if they jay-walk. A world in which the vehicle is programmed to stop for you would be a pedestrian’s paradise but would greatly interfere with traffic fluidity if pedestrians cross anywhere at any time. Therefore, shall we build fences on the sidewalks or put all vehicles underground or on top? We must think of these issues, as human beings will not follow the rules if they know they are safe.

LFDLC : Technological and political innovation are often faced with contestation. How do you address public acceptability issues?

Niels de Boer: Public acceptability is very important. Today, transport workers are taking on roles that are not quite well-defined. The question is: do we know and appreciate their role and added value? For example, a bus driver will look in the mirror to check that an elderly passenger is seated before driving off. If we go towards automation, will we look and include some of these tasks? I believe it is public acceptability which will determine where we are headed.

Jean Coldefy: Public acceptability issues are always raised when it comes to road pricing. Of course, alternatives must be provided before restraining the use of cars to influence behaviours. Depending on the constraint which the infrastructure user imposes on the general interest, they should be charged differently. A car with one passenger is definitely less efficient than a car carrying four passengers, and a commute during peak hours contributes to congestion.

In Sweden or Norway, people understand the need for road pricing because they understand that mobility must be financed. Although Gothenburg calls its road pricing schema a “congestion charge”, it is more akin to a revenue system meant to finance mobility as a whole. In the rest of Europe however, road pricing fails to be accepted by the population, except in Italy and the UK.

What is important in mobility is the generalized costs. The primary concern for commuters is travel time, much ahead of price. Managed lanes score very high when people are asked what would make them use car-pooling. This takes us back to the public space governance and funding issues that I previously mentioned. If the same entity managed public transport, park & ride, roads, and traffic, it would be much easier. Of course, mobility should be affordable, and affordability depends on income.

« If the same entity managed public transport, park & ride, roads and traffic, it would be much easier. »

LFDLC : What other challenges will have to be addressed to improve mobility in the coming years?

Lam Wee Shann: Now we are looking at our next generation of road pricing, going from a gantry-based to a satellite-based system. This system will be more responsive in terms of traffic management and will require less reliance on infrastructure. On top of this, it provides very good datasets that will ensure safety, improve traffic control, and foster R&D. Today, vehicles have In-Vehicle Units for the Electronic Road Pricing. This device automatically detects when the vehicle passes a gantry and will deduct the relevant fee. Through the new In-Vehicle Unit, a device adapted to the new satellite-based system, we will be able to push information to the motorist. We will for example be able to inform drivers if there is congestion on the roads they are travelling on.

Niels de Boer: Electrification and autonomous vehicles go hand in hand because electricity is an efficient and easy way to power a vehicle. For autonomous vehicles, electrification seems to me the only way to make it work. However, we have yet to look at the overall energy picture. For the average vehicles being tested, the whole boot and its fully-computed equipment require special cooling. Consequently, most of the vehicles require bigger engines just to provide energy. In Singapore’s hot and humid weather, air-conditioning is a necessary but energy-consuming amenity. For example, the Gardens by the Bay automated shuttles’ air-conditioning takes up to 50% of the energy stored in their battery. This is why electrification is a big challenge for Singapore.

Jean Coldefy: It is true that Singapore has achieved a very ambitious mobility policy. From very early on, much pressure was put on car ownership and car usage. However, the difference between Singapore and other – I should say all other – cities in the world lies in their geography. While the longest distance from one of Singapore’s edges to the Central Business District is 20km, many commuters elsewhere in the world must travel 40 to 50km to go to work. This explains why 250,000 cars enter the Lyon Metropolis every day. To solve this problem, cities will have to come up with an integrated system, offering efficient interfaces with park & ride options, mass rapid transit, and cycling infrastructure, consistent with a housing policy.

Furthermore, despite a low number of cars in traffic, most Singaporean highways are 3 to 4 lanes wide. Some of these lanes could be used as managed lanes or be dedicated to pedestrians or bicycles. Indeed, with 20-kilometer distances, I believe that an important share of travels could easily be travelled by electric bicycles. If adequate infrastructure is provided (shelter above bicycle lanes for example), hot and humid weather should not be a problem. To me, autonomous driving is not the future, except for public transport; electric bikes will be developed much earlier.

Karina Ricks: Pittsburgh has created two types of managed lanes. One is implemented on highways and dedicated to high-occupancy vehicles. The other offers bus-only lanes within the city. The problem we are facing with ride-sharing companies is that managed lanes on highways are very good: they take you from the country to the city. However, cars, once arrived in the city, feed traffic. In the city, bus lanes are not full, and ride-hailing companies are lobbying very hard to be able to use them for a fee. The price of time is very elastic. People are ready to pay more for travel time savings, and even more for certainty of travel time. So far, as we want to favour transit, we are not allowing ride-hailing companies to use bus lanes. If they start to have higher occupancy than just two people, we may allow them to use them.

One additional major mobility issue will be urban logistics. It actually already is. I do believe e-commerce is a great opportunity. However, it is very inefficient and creates new challenges by multiplying trips for small parcels, exacerbated by the emergence of Uber Eats, and other immediately on-demand product delivery services. What vehicle is the delivery taking? Maybe it could share a trip by taking a passenger in at the same time. Nowadays, we face what we call the walled garden: providers like Uber and Grab make you think they provide taxis, scooters, buses, but they don’t let you see what is on the other side of the wall. The mobility system they are offering is very attractive, but they keep out the competitors that would build a better system. The preference for this mobility model is based upon economic reasons, but we, as a government, need to be very protective against this phenomenon.

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Sending out an SOS

Behind the words: telecommuting

Behind the words: urban congestion

Toronto: How far can the city go?

Inventing the future of urban highways

Viktor Mayer-Schönberger: what role does big data play in cities?

Thomas Madreiter: Vienna and the smart city

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.