Towards a new role for local authorities in urban logistics?

The regulation of the flow of goods within the city is not a modern phenomenon — Roman cities already grappled with the issue of the movement of goods within their boundaries, both in their legislation and in the development of their public spaces. The externalities born of this flow are no news either. It is well-known that beyond congestion or visual and sound pollution, urban deliveries are responsible for 20% to 50% of local pollutants, particle emissions, and nitrogen oxides.

Three new phenomena are bringing the question of urban logistics to the forefront and forcing local authorities to think about the issue in a new light:

- With an estimated market of €424 million in 2014, the rise of e-commerce is the most visible manifestation of the emergence of powerful new actors in the area of urban logistics. While e-commerce only represents 7% to 8% of the movement of goods in the city, the interest and fears it produces are inciting urban stakeholders to rethink the mobility of goods (courier services, suppliers for retail, hospitals, artisans, and offices…) and as a result, that of people.

- City dwellers’ growing interest in urban problems and their demands for a better quality of life and well-being are prompting local authorities, as logistical actors, to integrate sustainable development constraints into the organisation of the movement of goods.

- Finally, today’s advanced knowledge of urban movements and a more accurate measurement of their impact offers an improved, multi-scale understanding of urban logistics and opens the way to new optimisation capabilities.

Local authorities are not powerless when it comes to logistics. For a long time, they have had a regulatory arsenal (Local Urbanism Plan, Territorial Coherence Scheme, road use rules…) aimed at managing movements and logistics facilities on their territory. Nevertheless, rules governing road use are mainly coercive, hard to enforce, and hardly an effective lever for action.

In addition, land rights provisions are struggling to control the sprawl of logistical activities, a sprawl that rejects storage, loading, unloading, and sorting operations to peri-urban and rural zones, and is incompatible with the reduction of negative externalities. In fact, the main drivers behind the installation of heavy logistics facilities remain a significant need for low-cost land, fast transport network connections, and residents’ unwillingness to accept the proximity of such activities. In addition, authorities work hard to integrate the complexity of the logistics chain and the multiplicity of its links (from producers to retailers and wholesalers through transporters and distributors) into a multi-sectoral urban project at the metropolis or inter-municipality level. Furthermore, the low margins in the logistics sector produce a strained, easily upset economic equilibrium, and consumers express many paradoxical expectations, such as the quick adoption of fast delivery models (in less than 24 hours, on Sunday, at night…) while rejecting the nuisances that they cause.

The current situation is thus based on a framework that is neither complex nor very restrictive, with private actors relatively free to impose their models. Such is the case of Amazon and its one-hour grocery delivery offer, which the City of Paris has unsuccessfully opposed on the basis of defending local shops. The city finds itself shaped by the expectations and practices of actors whose primary goal is to maintain their profits, perhaps at the expense of collective well-being. This does not, however, preclude some of these actors from engaging in virtuous efforts. However, in the absence of decisive choices from authorities and a transversal, metropolitan vision of the subject, the uncertainty surrounding regulations and financial support to come have the effect of impeding virtuous initiatives such as investing in fleets of green vehicles.

The city finds itself shaped by the expectations and practices of actors whose primary goal is to maintain their profits, perhaps at the expense of collective well-being.

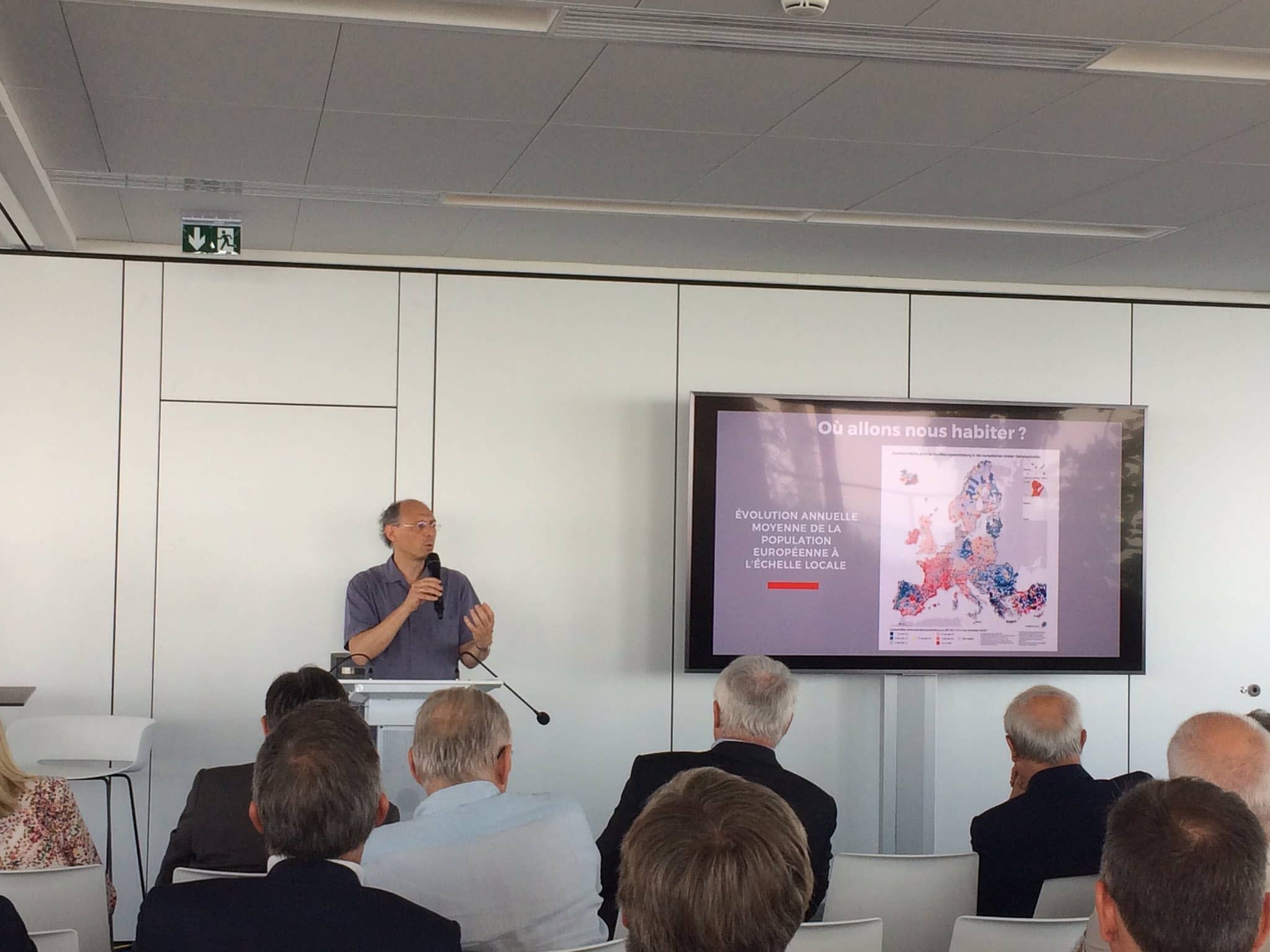

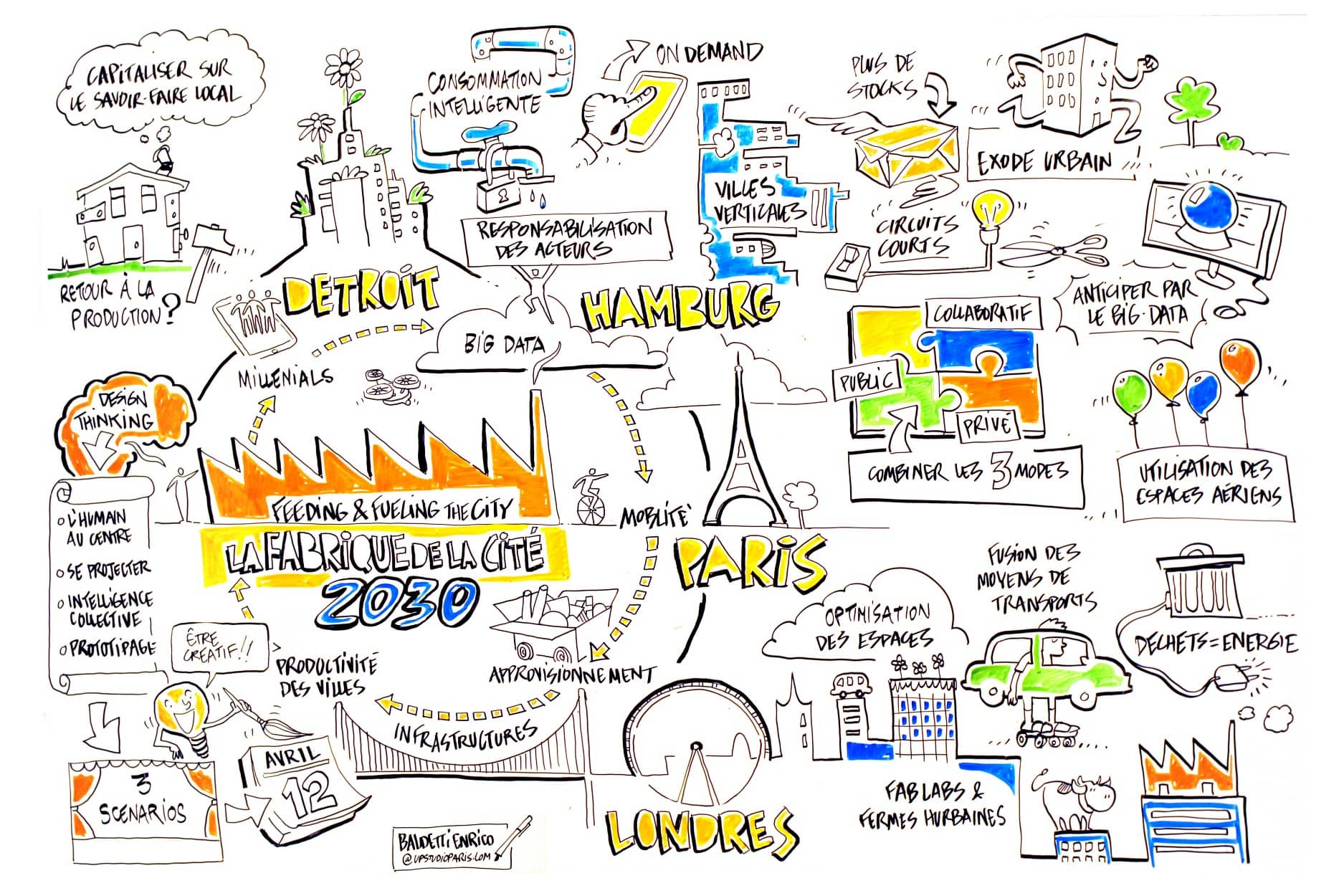

How do we invent new urban logistics based on this analysis of the current situation and its limits and challenges? During three co-construction workshops that brought together a panel of experts following the methods of design thinking, La Fabrique de la Cité created three mutually non-exclusive scenarios, which you may now discover in its new publication, “Feeding & Fueling the City — Three Scenarios to Rethink Urban Logistics”.

Local authorities have the capacity to play a key role in promoting a more effective logistics chain. Indeed, logistical real estate, recharging networks and adjustments made to the road network are all optimisation levers that fall outside of industrial actors’ control. This is why one of these scenarios sees communities taking a more voluntary stance and choosing strong political involvement in order to reaffirm their control over their territory and become a logistical platform. Far from a mere defensive posture aimed at hindering the rise of actors perceived as disruptive or even hostile, this strategy involves authorities showing proactivity and seizing new opportunities. Thus, local authorities can become an arbiter between the various actors of the logistical ecosystem with which they cooperate, and can work towards eliminating the negative externalities caused by logistics on their territory. This type of voluntaristic strategy is welcome by the actors of the logistics chain, as it is thought to guarantee a gradual and effective transition while taking their diverse interests into consideration.

Local authorities have the capacity to play a key role in promoting a more effective logistics chain.

This scenario, whereby the city’s territory could become an actual logistical hub, must go hand in hand with a redefinition of the use of urban space, in consultation with logisticians. This redefinition can in turn allow for an optimisation of the movement of goods, as well as improved quality of life in the city. Thus, local authorities could have an influence by finding new resources to ensure compliance with existing provisions, but also by reorganising parking (delivery spaces are curently used for other purposes 90% of the time), reconverting non-used spaces, integrating logistical real estate into urban development projects, or even making the use of public spaces (specifically the road network) flexible.

To fully understand and optimally manage movements of goods through the city, it would also be in local authorities’ best interest to put urban data[1] to better use. By promoting stakeholder coordination and the identification of optimisation measures, data could give authorities the opportunity to better organise merchandise transportation.

Finally, local authorities can be instrumental in restoring a city’s productive potential. Thanks to technologies that enable urban agricultural and industrial production (without aiming for utopian self-sufficiency), cities could reduce their dependence on supply sources they do not control (in 2007, 41% of fruits and 71% of vegetables arriving in Rungis came from outside of France) and shorten the distances travelled. Likewise, the positive reinforcement of virtuous recycling behaviours and the reuse of objects by citizens can help open the way to shorter circuits and a more sustainable supply for cities.

The intensification of the movement of goods in cities (a direct result of recent technological changes and of the growing hyper-individualisation of consumption) and the ensuing negative externalities make it all the more necessary for local authorities to stake out their position in urban logistics. Although there is no single solution to the challenges of urban logistics, these actors should aspire to recover as much control as possible on the movement of goods and the installation of logistics facilities.

Find this publication in the project:

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Back from Cahors

Rebalancing

Size, Network and People

Behind the words: food security

Inventing the future of urban highways

Spatial justice, managing the situation to enable development?

“Once Upon a Time”…

Feeding and fueling the city

Towards the Amazon city?

La Fabrique de la Cité

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.