Zero net artificialization: good intentions, wrong methodology?

“We have included the principle of zero net artificialization in the biodiversity plan. What you are now proposing goes further and stronger. So let’s go for it! You suggest avoiding new construction that bites into nature when rehabilitation is possible, so let’s take a stance! Let’s go! You advocate for a moratorium on new commercial zones on the outskirts of cities, let’s go! Let’s go, let’s take action!”. The speaker delivering this inflamed speech is none other than Emmanuel Macron, speaking to the members of the Citizens’ Climate Convention on Monday. The “zero net artificialization” objective (ZNA), i.e. the aim to suspend any net increase in the total amount of artificial surfaces, seems praiseworthy: at a time of ecological emergency, protecting biodiversity and natural soils is necessary. But what about the method? “Zero net artificialization” has several hidden flaws.

First of all, no one knows very precisely what artificialization is, or how to measure it. The government’s definition of artificialization includes any agricultural, forested, or natural soils the use of which has been modified, which means that parks and gardens are considered artificial, regardless of the ecological services they might provide. With this definition, a garden is considered no better than a parking lot, both being equally artificial! The measurement of artificialization also leaves to be desired: the evaluations carried out use widely different methodologies, allowing them to conclude, for some, that French soils are 9.3% artificialized, and for others, only 5.6%.

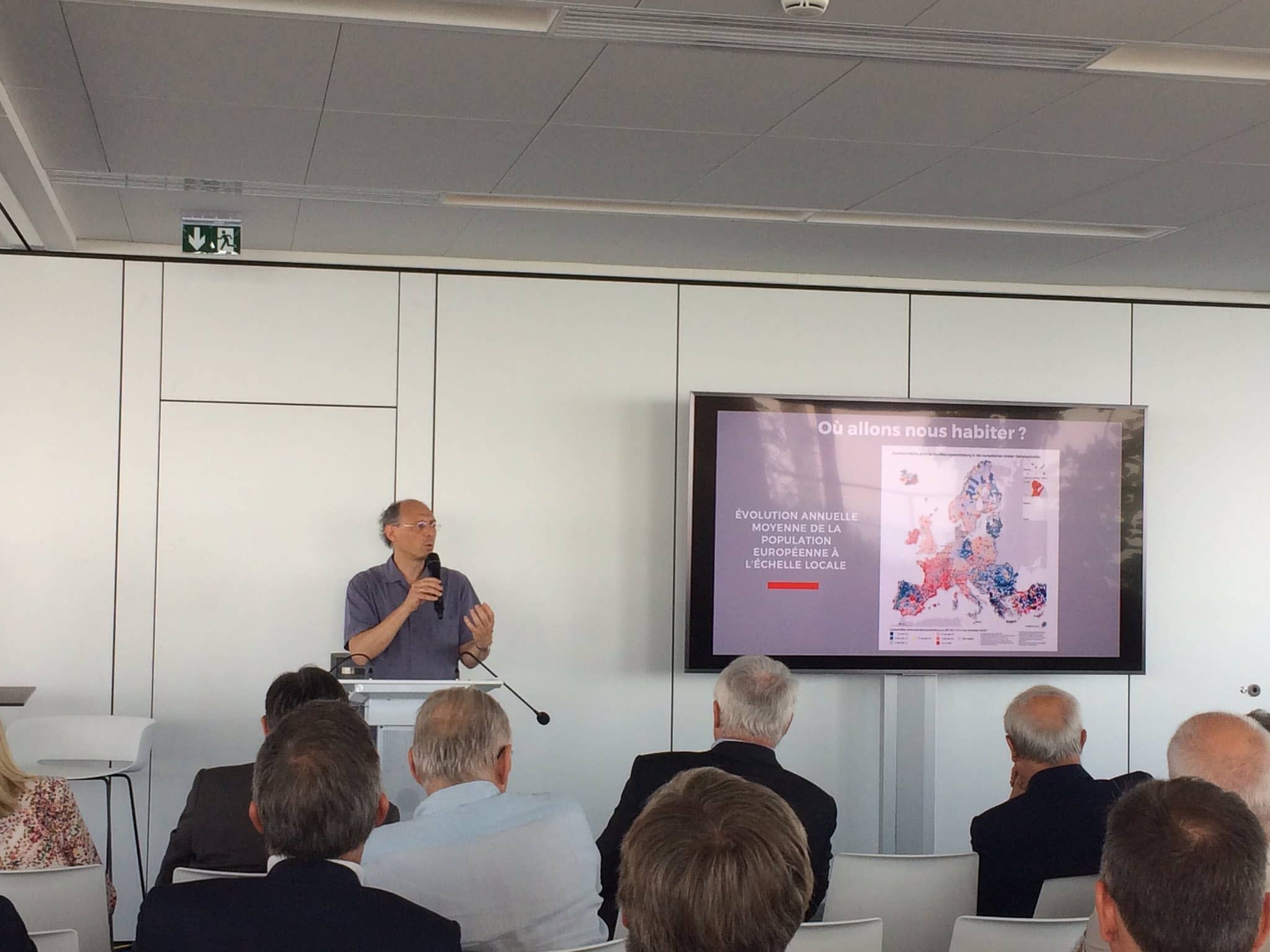

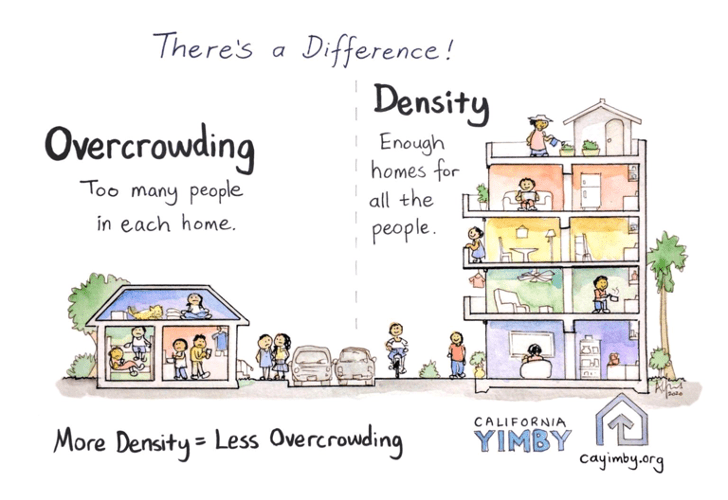

Second pitfall: there is a fundamental misunderstanding of artificialization, too often equated with urban sprawl and the image of an “ugly France” devoured by commercial areas. Reality is more nuanced: artificialization concerns both densely populated urban areas and rural territories. Nor is it the systematic consequence of vigorous demographic and economic growth, as it affects territories that are in demographic and economic decline. In Corrèze, for example, the rate of artificialization increased by 13% between 2006 and 2015, even as population grew by only 0.4%.

Third point: the ZNA policy suffers, fundamentally, from insufficient consideration of complexity. Thus, ZNA does not signal the end of soil artificialization, but rather enshrines the need to “renature” artificial surfaces as more are artificialized. While the idea may seem virtuous on paper, it does not stand the test of reality: soils and their characteristics are not identical or even similar and are therefore not interchangeable at will. ZNA also obscures the fact that not all artificialization is necessarily bad. Artificialized soils are mainly used for housing: half of the artificial surfaces between 2006 and 2014 were artificialized for housing, according to INRA and IFSTTAR.

Perhaps the debate on artificialization should be one about fragmentation instead. The latter threatens territorial equilibrium much more than the former, as sociologist and urban planner Éric Charmes pointed out as early as 2013. “It is not so much the disappearance of agricultural land, which is relatively limited anyway, that poses a problem as the nature and location of the artificial land and in particular the urban sprawl of rural areas […] The agricultural world is wrong to demand a halt to artificialization,” he concluded at the time. “It would be wiser to call for better organization of urban extensions and better planning. Charmes warns against the pitfalls of “land Malthusianism “, “a source of functional urban sprawl and a contributor to the housing crisis“.

No time to read? La Fabrique de la Cité has got you covered. Check our newsletter #35.

To be informed of our upcoming publications, please subscribe to our newsletter and follow our Twitter and LinkedIn accounts.

These other publications may also be of interest to you:

Helsinki : Planning innovation and urban resilience

Back from Cahors

Rebalancing

Size, Network and People

Behind the words: density

Inventing the future of urban highways

Spatial justice, managing the situation to enable development?

“Dig, baby, dig”

La Fabrique de la Cité

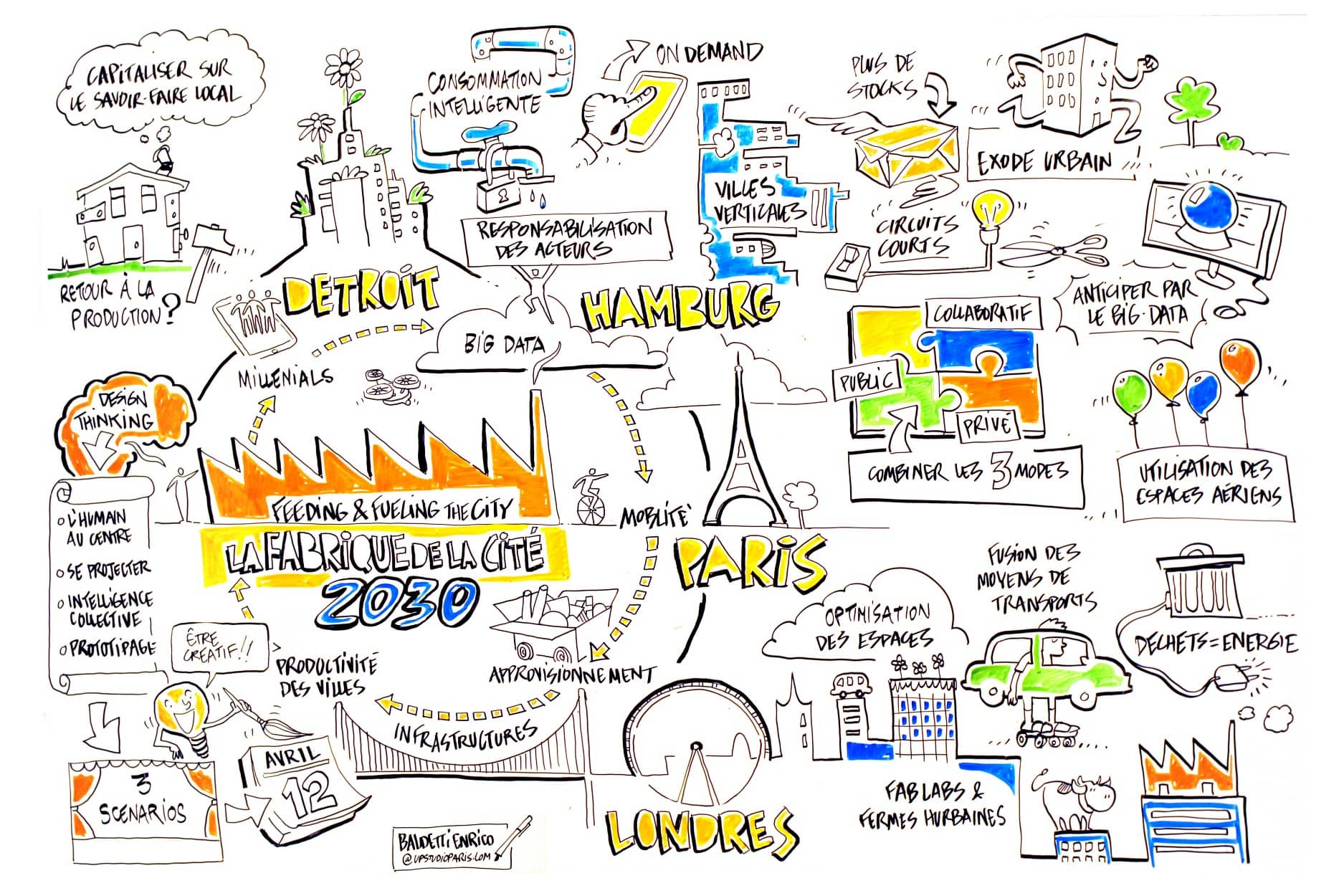

La Fabrique de la Cité is a think tank dedicated to urban foresight, created by the VINCI group, its sponsor, in 2010. La Fabrique de la Cité acts as a forum where urban stakeholders, whether French or international, collaborate to bring forth new ways of building and rebuilding cities.